As Percy Fields waits at Belt Junction, three freight trains stand nearby with their engines running and headlights shining in the chilly, predawn darkness.

Fields is president of the Belt Railway of Chicago, which is operating one of the trains. His job is to keep it moving.

But on this morning, like most others, the freight carriers must wait until a solitary Metra commuter train rolls through and opens up the track. Then they can blast their horns, clank and start to move.

Even then, they crawl at 5 mph through Belt Junction, a half-mile jumble of crumbling, century-old tracks along 75th Street between Western Avenue and Halsted Street on the South Side.

It’s Chicago’s most notorious rail bottleneck because, more than a hundred years ago, somebody decided five sets of tracks should merge into two and cross each other’s path.

It’s such a torment that Fields and other freight railroaders, plus Metra, Amtrak and government officials from across Chicago, have been working for more than 20 years to rip up Belt Junction and start over.

They want to spend $2.5 billion for new tracks, viaducts and flyovers to double the Belt Junction corridor’s annual capacity to 4 million rail cars.

Belt Junction is a critical building block in their plan to boost by nearly 80% their rail capacity in the Chicago region as a whole by 2052.

The project presents Chicago with painful dilemmas.

As has been true for hundreds of years, Chicago’s location at the bottom of the Great Lakes still brings intense pressure to move more freight.

But in 2024, Chicago is doing so with a rail infrastructure that’s starved for investment, losing ground to trucks and concentrated in the city in South and West side neighborhoods where Mayor Brandon Johnson is promising greater environmental justice.

The prospect of expanded rail traffic also presents convoluted policy choices, since it would get fuel-hogging trucks off Chicago streets in some cases and bring more in others. In the suburbs, it’s steadily transforming homes and farms into warehouses and parking lots.

So far, backers have raised about $900 million in railroad and taxpayer money to rebuild the Belt Junction area.

“When FedEx and UPS fly into O’Hare, nobody says, ‘you can’t land because we’ve got commuter planes that are going to be landing,’” said Fields, whose company sorts and exchanges individual rail cars among all the carriers in Chicago.

“At the Junction, freight trains have to take a back seat and let the Metra windows take preference,” said Fields, referring to freight railroad agreements to stand down during Chicago rush hours.

Even as they try to escape these 19th-century bottlenecks, Chicago railroaders freely admit they can’t stay ahead of the truck tsunami aimed at the city.

Chicago is still where the most railroads converge to exchange the most freight, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

Boosting rail capacity by 80% would be a monumental task because the Chicago region already has more tracks than nearly 40 U.S. states, according to CMAP.

Even if the railroads can do it, demand for freight shipping through Chicago during the next 20 years would be rising twice as fast, according to federal data cited by the railroads.

This will lure more trucks to a region where, according to Erin Aleman, CMAP’s executive director, road congestion is already the No. 1 obstacle to long-term economic competitiveness.

The railroads need trucks every time they load or unload the containers, which account for 40% of their Chicago-area volume.

And so far, they aren’t coming close to recapturing market share from trucks.

According to Trains magazine columnist Bill Stephens, between 2013 and 2022, the freight volume excluding coal carried by the four big U.S. railroads grew an average of 2%, compared with a 26% tonnage increase for trucks.

In 2024, some of the railroads’ most important efforts to turn the tide, including a joint campaign by BNSF Railway and J.B. Hunt Transport Services to double intermodal or container volume, are taking place in Chicago.

The region has an enormous stake in the success of these efforts.

According to CMAP, industries reliant on frequent goods movements already support a quarter of all jobs in metropolitan Chicago. And more freight on railroads would mean fewer toxic emissions per shipment than on trucks, according to the Sierra Club.

To build on these potential strengths, the railroads may need to renegotiate a peace treaty they signed with the city of Chicago two decades ago.

That’s when they formed a public-private partnership called CREATE to rebuild Belt Junction and other bottlenecks. It’s an acronym for the Chicago Region Environmental and Transportation Efficiency Program.

CREATE includes five big North American freight railroads, Metra and Amtrak, and various Chicago, Springfield and Washington government agencies.

Railroad executives and government officials formed the group in 2003 and then agreed to share the cost of fixing rail bottlenecks and expedite environmental approvals.

CREATE has already started building a flyover to carry north-south trains up and over Belt Junction.

The Federal Highway Administration cleared the way for this construction with an environmental approval in 2014.

In the approval, for which the agency did no site-specific computer modeling for pollutants like diesel soot, the highway administration declared CREATE can double rail traffic in the Belt Junction area without damaging air quality.

The agency reaffirmed this finding three years ago and said in a Jan. 19 email it has no plans to revisit it now.

At 47, Mayor Johnson comes from a different generation than the officials who agreed in 2005 to expedite environmental approvals at Belt Junction.

He came into office with a public health mindset. He promised to begin closing the eight-year life expectancy gap between Black Chicagoans and everybody else.

This promise helped lead to his release of Chicago’s first-ever “Cumulative Impact Assessment” in September.

The assessment used metrics like proximity to rail, truck traffic and warehouses to show that parts of Belt Junction lie in what the city has designated an “Environmental Justice Neighborhood.”

The city views these areas as the most vulnerable to and most affected by pollution, and Johnson has promised to protect them.

And they were wrestling with truck congestion long before the Belt Junction renovations.

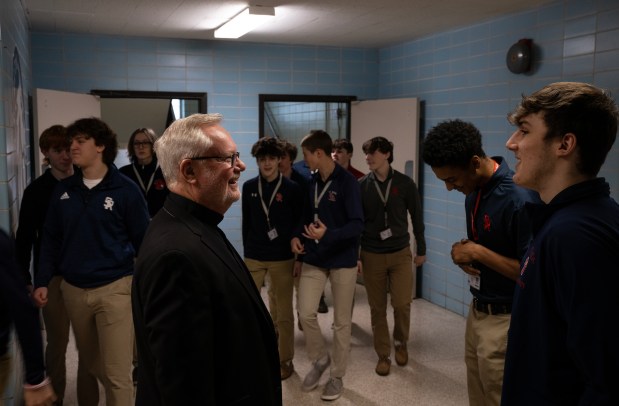

St. Rita of Cascia High School at Western and 77th Street is surrounded on three sides by trucks entering or leaving a Norfolk Southern intermodal yard called Landers.

Last year, the trucks at Landers were so backed up they blocked entrances to the school and nearby businesses, said Deacon John Donahue, St. Rita’s president.

Donahue said he asked for and got a meeting with the railroad. He credits Norfolk Southern with working to resolve the backups and keeping St. Rita and the city informed since then.

Separately, he complained to city, state and federal officials about crumbling pavement on Western Avenue because of trucks. It’s since been resurfaced.

“We host police and fire line-of-duty funerals in our chapel. That’s a three-day shutdown. Every athletic activity, every academic activity is canceled and we turn our campus over to the city of Chicago.

“We do it because that’s how invested we are in what happens in the city,” Donahue said.

“We speak up not only on our behalf but on behalf of our entire community,” he said. “We’re not going to just be ignored.”

On the Belt Junction tracks near St. Rita, fleets of repair vehicles often appear as soon as trains pass by.

That’s because the Victorian-era viaducts holding Belt Junction 16 feet in the air are getting pounded by freight trains that on average are twice as heavy as they were a century ago.

More than 100 Metra, Amtrak and freight trains pass through the Belt Junction area each day. The chance that crumbling viaducts will close one of the tracks stands at 1 in 3 by 2037, according to CREATE.

‘Rolling in money’

Looking back from 2024, it’s hard to imagine the frenzy that gripped Chicago’s railroads when Belt Junction was built.

Dozens of railroads were racing to get rich by building connections to Chicago — often with just one track and one or two rail yards.

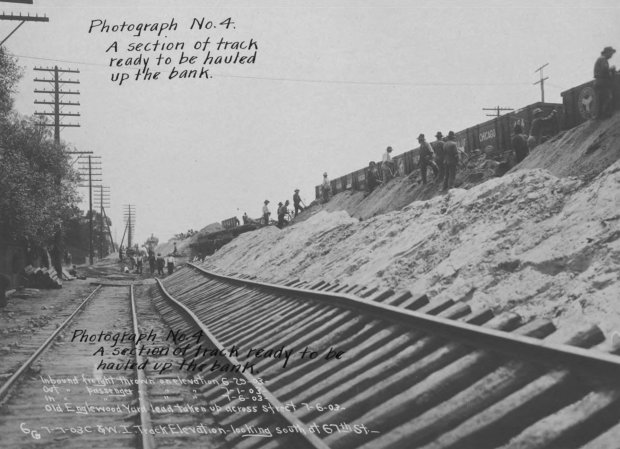

Beginning with the 1893 World’s Fair, they also scrambled to elevate freight tracks citywide — at their own expense — to quell the uproar over hundreds of Chicagoans getting killed every year at street-level crossings.

The railroads imported boxcar after boxcar of sand from the Indiana dunes to build up the tracks.

They mostly hired Italian immigrants who cleared out each boxcar in 20 minutes using nothing but shovels. For this, they got paid $1.75 a day or about $55 in today’s dollars.

Chicago railroads flourished as part of the vast industrial buildup that helped the United States win two World Wars.

Airplanes and taxpayer-funded highways prompted a postwar decline that perhaps reached its nadir on Jan. 1, 1999.

That’s when a three-day blizzard froze Chicago trains in place wherever they were standing. Some freight cars couldn’t move again until baseball season, according to Trains magazine. As the crisis deepened, Mayor Richard M. Daley launched a blue-ribbon task force.

In one of its first and most consequential acts, the task force announced a multidecade sequence for 70 CREATE projects.

It was a smorgasbord of flyovers, grade crossing separations and upgraded tracks spread all across the region.

The task force also agreed that only the unanimous consent of all the railroad executives, elected officials and regulators involved could alter their basic plan.

They’ve mostly maintained their original sequence of projects. And unanimous consent was a huge breakthrough, said Gerald Rawling, then a transportation analyst for an institutional precursor to CMAP.

At the time, the railroads were brawling with Daley over his insistence they abandon a small rail spur near McCormick Center.

The railroads bowed to Daley on the spur as the price for getting public money for CREATE, Rawling said. But they drove a hard bargain.

They agreed to pay just 15% of CREATE’s initial budget while continuing to invest in their own tracks and rail yards.

Government officials promised to help seek public funding for CREATE, to swallow any cost overruns, and later to expedite environmental reviews.

“I wouldn’t say the city capitulated,” Rawling said. “I think they reached the point of saying, ‘Look, if we don’t collaborate, the railroads are going to do this someplace else, like in Memphis.’”

Nobody was sure if the railroads would actually move. But Rawling described this threat as “a club the city was subjected to for a long time.’’

Ultimately, the glue that holds CREATE together is the overlapping ways the projects help people.

The public will benefit from a Belt Junction flyover that eliminates a notorious grade-level crossing at 71st Street near Western.

The new crossing will save Englewood residents time and reduce noise and emissions from the cars and trucks often stuck waiting there now.

The public will also get new streetlights, accessible sidewalks and a shot at CREATE-related jobs and construction contracts. CREATE donated $600,000 to nearby schools in a nod to environmental justice.

Norfolk Southern gets a dedicated track into the Landers yard. That’s good for Norfolk Southern, and it means the railroad’s trains won’t block CSX or Union Pacific as they come and go.

This freedom can’t come quickly enough as CSX adjusts to new market realities, said Tom Livingston, vice president for government affairs at the railroad.

“Whereas our largest customers in Chicago might have been coal, now we’re dealing with UPS, Amazon and Walmart,’’ Livingston said. “They have different sensitivities in terms of time.’

Metra will also get a dedicated track on a flyover running above Belt Junction for three-quarters of a mile.

The new flyover will allow Jim Derwinski, Metra’s executive director, to schedule trains throughout the day. And more trains, he said, are Metra’s best hope for building ridership back to pre-pandemic levels.

“This system was never built to do what it’s doing,” Derwinski said. “We need much more infrastructure in Chicago to be more fluid, to have more resilience and certainly to grow.”

Amtrak, too, counts itself as a Belt Junction beneficiary.

That’s because one of the flyovers could eventually allow Metra’s SouthWest Service to use the LaSalle Street station downtown and, in turn, free up badly needed space for Amtrak at Union Station.

The talks leading up to CREATE had another beneficial impact. They fostered better day-to-day communications to keep trains moving.

During twice-daily conference calls, a central traffic-monitoring staff presents real-time data that all the railroads can use to cut shipments during blizzards or park trains several states away to keep Chicago clear.

With all these benefits, it’s a wonder that after 21 years, CREATE has raised only about a third of the $5.8 billion it needs for its original list of projects.

Just last month, CREATE failed to make the cut when the U.S. Department of Transportation announced dozens of infrastructure grants nationwide.

CREATE, which for its next step needs $260 million to rebuild crumbling viaducts at Belt Junction, vowed to keep seeking public money.

But Marty Oberman, the chairman of the Surface Transportation Board and the country’s top railroad regulator, sees another problem.

Chicago is a key battleground as railroads struggle to figure out the future

Oberman said the railroads are shortchanging not just CREATE but the entire U.S. economy because Wall Street is demanding and getting too much of their money.

He denounced the railroads’ limit on contributions to CREATE. When he was at Metra, this informal, self-imposed limit was generally 25% of the cost of each project, he said.

“The railroads are rolling in money, so it frustrates me to have to say, ‘If we offer you a little bit more taxpayer money, would you spend a little more of yours?’” Oberman said.

During the last 14 years, the six big North American railroads earned $336 billion in profit, sent $253 billion to Wall Street in the form of share buybacks and dividends, and spent just $40 billion to expand their network, Oberman said at an investor conference in November.

And they have 20% fewer workers today than before the pandemic.

A former Chicago alderman and Metra chairman, Oberman praised CREATE’s unanimous decision-making as a model for the nation.

But the railroads are failing to protect the public as legally required, he said. Congress cemented this obligation, called the common carrier doctrine, when it cracked down on railroad monopolies in 1887.

Chicago will suffer great harm, Oberman said, if the railroads continue to lose market share to trucks.

“The roads would be so congested that at some point, traffic wouldn’t move at all,” Oberman said. “People would stop locating their businesses here.”

Eric Jakubowski, chief commercial officer for Chicago-based Anacostia Rail Holdings, said that if the railroads don’t begin to focus less on Wall Street and more on customers, they may never fill their new freight capacity in Chicago.

“You have to be bullish that the railroads have cleaned up their act and have enough resources to actually reclaim market share from trucks,” said Jakubowski, whose company owns small, so-called short-line railroads in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York.

“Right now, the jury’s out,” said Jakubowski, who counts the 182-mile Chicago South Shore & South Bend Railroad among his company’s holdings.

Reducing emissions

In the Chicago region, two of the most significant attempts at railroad growth are happening 30 miles southwest of the city in Joliet.

At the eastern terminus of its high-speed tracks to Los Angeles, BNSF is conducting a high-stakes experiment with J.B. Hunt, a trucking company from Lowell, Arkansas.

In November, they launched a premium intermodal service called Quantum.

Through Quantum, J.B. Hunt identifies trucking customers who could be lured back to railroads and arranges priority access and tracking for them on trucks and on BNSF trains.

They’re promising competitive prices and 95% on-time performance. This latter metric is equivalent to trucks and nearly 40 points higher than BNSF’s post-pandemic low.

If they can do it, they and other railroads could pull as many as 11 million container shipments a year back from trucks, according to J.B. Hunt estimates.

In its busiest year, BNSF handled just over 5 million, said Jon Gabriel, the railroad’s vice president for network strategy.

With J.B. Hunt tracking freight, they also have a shot at boosting traffic through their existing yards by 20% without needing more space, Gabriel said.

Each year at BNSF in Elwood near Joliet, this could mean 175,000 more “lifts,” or container movements on or off a rolling chassis or trailer, and hundreds of thousands more trucks, according to CMAP and railroad data.

Gabriel said BNSF is pitching its Quantum intermodal service partly to customers who want fewer carbon dioxide emissions.

He said that on the kind of 2,000-mile cross-country trip favored by most of the railroad’s intermodal customers, trains emit 60% to 70% less CO2 per shipment than trucks.

BNSF also hopes to cut emissions at the end of the trip – and to put at least a dent in Chicago’s truck surge – by sending more containers out of its Elwood yard by train instead.

Specifically, BNSF wants more crosstown transfers to freight yards operated by other railroads to occur on steel-wheeled trains instead of rubber-tired trucks.

Four miles northeast of BNSF at its Global IV intermodal yard, Union Pacific is also seeking more crosstown transfers on steel wheels, even as the yard’s rapid growth puts many more trucks on Joliet highways.

Union Pacific meets with other railroads every quarter to identify more loads they can profitably exchange in Chicago using trains, said Luke Slawson, general director for northern states intermodal operations.

Currently, he said, about 70% of Global IV’s containers leave on trucks. Of the total, 6 in 10 leave Illinois altogether.

With a new fleet of mostly self-driving cranes, the railroad plans to boost Global IV’s annual lift count by 50% to 1.2 million in a few years, Slawson said. This increase would require hundreds of thousands of additional trucks.

A mile and a half from Union Pacific, a Kansas City real estate company named NorthPoint Development has built three warehouses with more than 1 million square feet each.

This means they’re each bigger than the passenger terminal at Midway Airport.

NorthPoint has announced plans for 33 warehouses on what is now a mixture of suburban homes and farmland southeast of Joliet, Patch.com reported in November.

Slawson said Union Pacific loves being part of Joliet’s warehouse boom.

“Out here, the intermodal yards are located near the distribution centers, and there’s land for more distribution centers to be built,” he said. “We have access to all the major freeways.”

Back on the South Side, the intermodal yards near Belt Junction also have access to freeways. Just not so quickly.

The trucks that haul containers to and from Norfolk Southern near St. Rita or the CSX yard on 59th Street must drive 3 miles east to reach I-94, 3 miles south to reach U.S. Route 20, and 5 miles north to reach I-55.

No matter where they’re going, they drive through dense city traffic. And these are not just any trucks.

Big companies like Werner Enterprises or Knight-Swift typically use trucks no more than three or four years old for coast-to-coast trucking, said Gary Bishop, a retired University of Denver chemist who spent years doing real-world emissions tests on diesel trucks.

Bishop said these big companies then sell the trucks into a used vehicle market where they may last another 30 years and generate diesel emissions eight times more lethal than when they were new.

Jason Hilsenbeck, president of LoadMatch, a Naperville company that helps drivers find freight to haul, said that in Chicago about 20,000 drivers regularly carry containers to and from rail yards.

Of those, about 60% are independent owner-operators, often driving older trucks. Many of the rest work for big companies like UPS.

Nobody knows precisely how growing truck traffic will affect the health of suburbanites and city residents near freeways and intermodal yards.

However, the Chicago Department of Public Health has filled its new Cumulative Impact Assessment with metrics for residents’ proximity to rail lines, truck routes, warehouses and container storage lots.

The Belt Junction census tract at 75th and Western in the Chicago Lawn neighborhood is in the 93rd percentile of all Chicago neighborhoods for being most exposed to environmental dangers.

Nobody knows how many additional trucks the Belt Junction renovations will bring.

But just two intermodal rail yards, Norfolk Southern Landers and CSX at 59th Street, lifted almost 700,000 containers onto or off trucks in 2021.

Both yards plan to expand as Belt Junction gets rebuilt over the next decade. Neither would say how much.

The highway administration didn’t address this issue in its 2014 Belt Junction approval.

In an email to the Tribune, CREATE said future traffic into the yards depends more on market conditions and capacity constraints than on dedicated tracks and other improvements from the Belt Junction renovations.

The main value of the renovations, according to CREATE, “is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of carrying long haul freight of all types (not just intermodal).”

In its emails, CREATE said the renovations will reduce emissions in environmental justice neighborhoods by reducing waiting time for trains, cars and trucks.

The highway administration, for its part, did not address questions about the failure of railroads to install pollution-fighting equipment in locomotives at anything like the rate the agency predicted in its 2014 Belt Junction approval.

In its emails, CREATE said the Belt Junction renovations will prevent the railroads from losing even more freight to trucks and thereby keep emissions lower than they would be otherwise.

Even if this is true, people who live near the intermodal yards will still be surrounded longer than anyone else in Chicago by the region’s oldest and dirtiest trucks, according to Scott Bernstein, co-founder of the Center for Neighborhood Technology, an environmental group.

And the Chicago region is already failing to comply with EPA limits on ozone, an invisible, lung-scarring gas associated with cars, trucks, steel mills and power plants.

The agency also plans to lower its limit on PM2.5 or tiny, lung-penetrating particles in diesel soot. This will make it harder for Chicago to comply with PM2.5 standards.

Bureaucratic maneuvering

Johnson can’t make these problems disappear. But, Bernstein said, he’s also not helpless.

On a policy level, he said the mayor’s best shot at cutting freight emissions may be to help short-line railroads like Anacostia Holdings.

He said these small railroads already play an outsized role in helping big carriers like Norfolk Southern lure customers away from trucks.

But to begin exploring such possibilities, Bernstein said, Johnson needs to reorient CREATE to focus on freight movements generally, and on trucks, and not just on rail bottlenecks.

“There is no CREATE sub-manager for the truck fleet,” Bernstein said. “There should be somebody accountable for reducing congestion at these intermodal terminals and how much is shipped by truck to begin with.”

Johnson referred questions to CREATE.

In their recent application for federal dollars for a portion of the Belt Junction renovations, CREATE organizers said they’ll need additional city and state permits as the project begins to affect public streets and alleys.

If Johnson chooses to use them this way, these additional permits could enable him to reshape CREATE to his liking, said Dick Simpson, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“If the mayor and the congresspeople focus on this project enough, they do have leverage,” Simpson said. “And if the railroads want to finish the project, there has to be some flexibility.”

In addition, the national EPA is not a party to the highway administration’s agreement to expedite Belt Junction environmental reviews, said John Mooney, air quality director for EPA Region 5 in Chicago.

Mooney said the EPA can still intervene if expanding rail and truck traffic damages Chicago’s ability to meet federal air quality targets.

All this bureaucratic maneuvering comes too little and too late for Kenny Doss Sr., who lives on 66th Street north of Belt Junction.

He’s 50 years old with asthma and “very bad sinuses.”

But Doss, who owns a small trucking company, worries most about what trains and trucks are doing to his grandchildren.

“If they get air pollution at a young age, how are they supposed to grow?” Doss asked.

During a 90-minute drive through Englewood, Doss gestured toward burned-out buildings and vacant lots and talked about how — even on bright summer days — the neighborhood feels deserted.

He also rattled off the names of half a dozen intermodal terminals that are expanding on the South Side.

These include a Norfolk Southern yard where a grass-covered berm along Garfield Boulevard near the Dan Ryan freeway now prevents generations of former residents from turning south onto Normal Avenue.

If they could make the turn, they’d still be able to drive past hundreds of homesites the railroad has acquired to expand the yard.

Doss grew up about a mile away and often visited family and friends at the now-demolished homesites.

“Everything you ever knew as a kid, it was like it never happened,” Doss said.

“We see all these containers coming and going, but why does the community around the railroad look the way it does?” Doss asked. “We should be able to flourish just as much as the railroads.”

John Lippert is a freelancer.