John Pica thought about that hot summer when Baltimore didn’t have enough money to open its public swimming pools and Peter Angelos anonymously wrote a check.

For Alan Rifkin, it was the drawerful of thank-you notes from not just law clients, but those who had reached out for help with their rent or getting into college.

And for former Democratic Gov. Parris Glendening, the memory was Angelos complaining to him about how little the state had paid him for his legal services and using the word “only” in reference to “$150 million.”

Those were among what sprang to mind when, in the space of the past four weeks, the family of the now-incapacitated Angelos sold first the Baltimore Orioles and then the renowned law firm that had won hundreds of millions of dollars for victims of asbestos.

The two local institutions were the source of much of the wealth the 94-year-old Angelos amassed over his active lifetime, as well as the political power he came to wield and the largesse he spread around.

But, while the dual sales secure the future of the team and the law firm, they don’t transfer the generosity and community and political engagement of one of Maryland’s most prominent citizens, say those who have worked with him over the years.

“In some respect, there will be a void,” said Rifkin, himself an influential attorney. “Someone like Peter Angelos, who was larger than life and so civic minded and philanthropic and a champion of so many folks who needed his help, is irreplaceable.”

Angelos retreated from his once high-profile public life as his health deteriorated, and as of about six years ago could no longer work or handle his affairs. A family feud erupted in 2022 in Baltimore County Circuit Court over control of his assets, and in its wake, pieces of his self-made fortune were sold off.

At the end of January, news emerged that David Rubenstein, a Baltimore native and private equity billionaire, had agreed to buy the Orioles in a deal that valued the team at $1.725 billion. And on Wednesday, a judge approved the sale of the law firm to three of its senior attorneys. The family also has sold several properties from Angelos’ large real estate portfolio, with One Charles Center, the downtown architectural landmark where the law firm is headquartered, still on the market.

The dismantling of the Angelos empire strikes Pica, a former Democratic state senator, as one more loss of “homegrown business leadership.” Baltimore once had a slew of banks, retailers and other major businesses that were locally owned and led, Pica said, harkening back to a time when, for example, a Mason ran Legg Mason.

“I think those individuals are not around any more,” said Pica, a former member of the Angelos law firm. “I think Peter’s the last one.

“It’s one less person who can pick up the phone and call the governor or call the mayor,” Pica said. “Peter made it an issue to become involved in civic activities and civic problems. He forged his will on Baltimore and Maryland politics.”

In this file photo, Orioles owner Peter Angelos and then-Gov. Parris Glendening speak at a news conference at Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

Famously workaholic and loathe to delegate, Angelos not only ran his legal and baseball businesses, but was ubiquitous beyond the courtroom and the owner’s suite at Camden Yards. He was a major Democratic political donor locally and nationally — with former Gov. Robert L. Ehrlich the rare Republican to receive his support — and was not shy about promoting his own interests in Annapolis and Washington.

On one occasion, he brought Orioles star Cal Ripken Jr. for extra clout as he pressed state lawmakers for legislation so narrowly targeted to benefit him that it was known as “the Angelos bill.”

A one-term Baltimore City Council member himself, from 1959 to 1963, his subsequent tangles with mayors and governors could be epic, over such things as his efforts to build a hotel near the convention center, downtown redevelopment plans that would threaten his own real estate holdings and a host of issues affecting the state-owned Camden Yards or his law firm’s litigation.

“Quite a character,” Glendening said dryly.

Glendening had to negotiate several disputes Angelos had with the Maryland Stadium Authority over issues like parking at Camden Yards and parity with the Ravens, and over how much the lawyer would be paid for handling the state’s litigation against tobacco companies.

Angelos’ initially was to receive 25% of any money recovered. But after the state received about $4 billion, it ultimately negotiated the fee down to $150 million. Glendening said he subsequently saw Angelos at an event in Baltimore, where the lawyer griped that he had been “cheated.”

While Angelos could sometimes be “plain nasty,” Glendening said, he was also generous. He expressed respect for all Angelos accomplished.

“I think the city owes him a lot, the state owes him a lot,” he said. “He was a mover. He was a shaker.”

Lainy LeBow-Sachs, a top aide to Democrat William Donald Schaefer during his terms as Baltimore mayor and Maryland governor, recalled the two men’s personal friendship and politically useful alliance. Angelos was Schaefer’s point man, for example, in the fight to get an NFL team back in Baltimore during some of the drought years after the Colts slipped away in the dead of night in 1984 and before the Browns were lured to town to become the Ravens in 1996.

“Schaefer knew he couldn’t do the job himself,” LeBow-Sachs said of the late politician’s approach to getting things done. “If you could do something for him, he loved you.”

“It’s one less person who can pick up the phone and call the governor or call the mayor.” — Former state Sen. John Pica

Loyal to the city he grew up in, the son of a Highlandtown tavern owner, Angelos gave generously to institutions like the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and the University of Baltimore, whose law school building bears the name of his parents. Beyond his wide range of institutional contributions and service on multiple boards were the often quiet donations to people who found themselves in a pinch and sought his assistance.

“Peter took enormous pride in the success of the Angelos law firm,” Rifkin said. “It wasn’t the financial success. He had a drawer in his desk of handwritten letters from people who he had helped. That gave him the most pride.”

The fate of the Angelos law firm was among the battles fought by his wife and sons. In June 2022, younger son Louis, a lawyer who had been managing the practice in his father’s absence, sued his older brother John, the Orioles’ CEO, and their mother, Georgia, over what he claimed were their efforts to control the family assets and deny him a fair share. Georgia Angelos then sued Louis for transferring the law firm to his name, which he said was necessary because of his father’s disability.

The fight landed the law firm in conservatorship in January 2023 and, the following month, family members settled the suits under undisclosed terms.

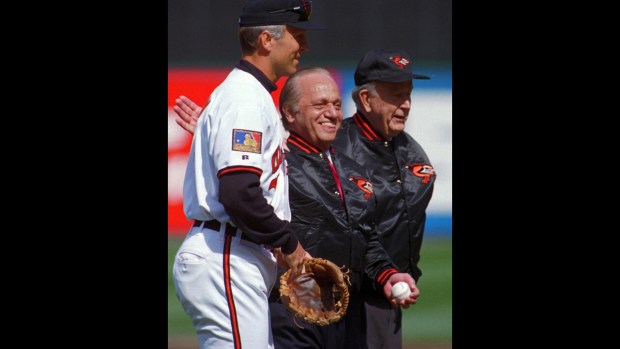

Orioles vs. Kansas City for opening day. as Cal Ripken, Peter Angelos, and then-Gov. William Donald Schaefer pose for a picture after throwing out the first pitch.

With Peter Angelos incapacitated and his firm transferring to three of its attorneys and the team to Rubenstein, it remains unclear what kind of public role his family might play in the future. The family members did not return requests for comments for this article.

It’s hard to imagine that they, or anyone really, would similarly dominate the civic and political landscape in quite the same way, some believe.

Life in the “fishbowl,” said longtime marketing executive David Nevins, “that’s clearly not for everyone.”

Nevins, during his time as president of the Center Club downtown, turned to Angelos, a member, with a proposal to create an Orioles pub within the fancy space. Angelos footed the bill and let the club use the Orioles name.

“Peter obviously enjoyed the very public stage of being a major league sports owner,” Nevins said, while the sale of the team and the law firm suggests his sons have chosen “to move on to do other things with their lives.

“Nothing lasts forever. Life goes on, and the world changes,” he said. “Sometimes your kids follow in your footsteps and sometimes they march to their own drummer.”