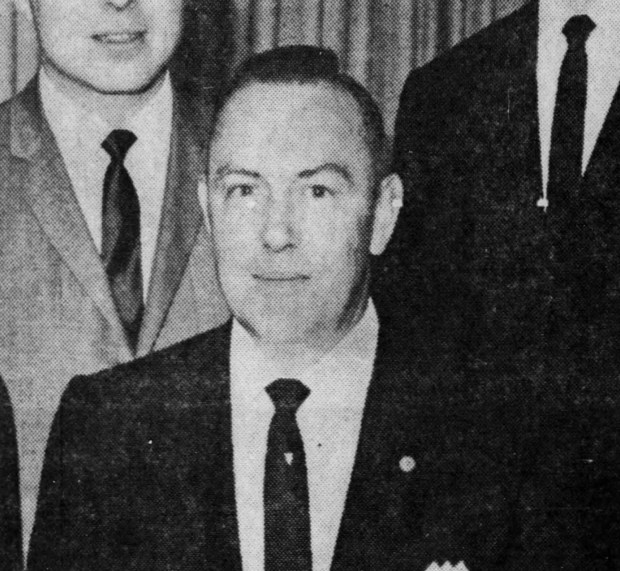

Chicago’s Pullman neighborhood likely would look much different if not for the efforts of Americo L. Lisciotto, a draftsman who lived on Champlain Avenue.

The Italian immigrant was behind an effort to save part of the neighborhood from demolition as the first elected leader of the Pullman Civic Organization.

Though his story isn’t well known in most of the Chicago area, his memory was brought to life last weekend by the Pullman House Project, which offered tours of his former home, along with the Pullman House Project Welcome Center and coffee shop at 605 E. 11th Street.

Lisciotto’s former home at 11121 S. Champlain Ave., on display just in time for National Park Week, includes the furniture and artifacts that a working-class Italian family might have owned. On the wall there’s a 3-D light box of Venice’s grand canal and a side table is topped by an ashtray and Lucky Stripes cigarettes. The television is a 1949 model and a rotary phone is part of a table and chair arrangement. An album by Mario Lanza is ready to play on the old record player.

Lanza “was an opera singer, did a lot of movies,” said retired architect Mike Shymanski, a founding member and past president of the Bielenberg Historic Pullman House Foundation who helped organize and lead the tour. “In the 1950s he was a heartthrob.”

Both Shymanski and his wife, Pat Shymanski, a former attorney who is president of the Bielenberg Foundation, have lived in the community for years and volunteered countless hours to ensure its place in history. Pat Shymanski can also be found making coffee drinks and scones in the welcome center’s coffee shop.

In the Lisciotto home, there are chenille bedspreads in the two small bedrooms. The former kitchen/dining room, which was used for cooking, eating, entertaining and more, was also the room where Lisciotto helped plan meetings that proved crucial to the character of the Pullman neighborhood. An urban redevelopment plan in the 1960s would have bulldozed swaths of homes George Pullman had built around 1880 to house workers at his railcar factory.

The Pullman neighborhood was “a little different from any other factory town,” said Alfonso “Nino” Quiroz, of the Pullman House Project, who helped create the tour program.

“This one was special because he hired an architect and landscape designer and created the homes to almost resemble train cars,” he said. “(The homes were) very well built, same color scheme, really focused on detail.”

Like other volunteers, Quiroz grew up in the neighborhood, though he now lives in New York. His family came to Pullman in 1906 and many of his ancestors worked for Pullman. His parents still live there.

By the 1960s Pullman’s homes were becoming run down, and the company was on its last legs. The popularity of passenger train transportation had dwindled as airline travel gained purchase, and the city wanted to relocate heavy industry to the Lake Calumet area not far from Pullman, Quiroz explained.

“They thought Pullman would be a perfect area to redevelop as warehouses and use that to really entice the development of this whole new industrial area,” Quiroz said.

When area residents got wind of the plans, Lisciotto encouraged residents to spruce up their homes and organized a neighborhood cleanup. He didn’t want to move, and he didn’t want his mother, who lived next door, to be relocated either.

That resistance and preservation effort ended up having big results.

“The reason it’s so important is because this is where the seed of the National Park was born for Pullman,” Quiroz said.

The restoration of Lisciotto’s home went down to the flooring, where volunteers uncovered the original flowery linoleum after old carpeting was stripped.

“Those are some of the fun things about restoring an old house,” said Shymanski, who worked in urban planning and was central to bringing this home back to life. “We love history and think it’s very important to preserve places. “(Pullman) has such a strong identity as a place. It has a visual unity, all made of brick and has lots of row houses.”

Volunteers from the Pullman House Project have restored other structures from the 1880s and 1890s and the group plans to showcase period homes from the 1920s and 1940s at future events.

As for the Lisciotto home, even the original wooden floors are visible in some rooms.

“If they could only talk,” said Gary Meredith, of Cedar Lake, Indiana, who grew up in Pullman and was on the tour with his wife, Christi. “Great memories.”

Meredith, a retired carpenter, remembers being 12 and helping his dad repair plumbing in the former Hotel Florence, another landmark. He also remembers the closeness of the neighborhood and a former grocer who helped out residents with credit.

“All the older people in the neighborhood, he would let them have groceries and pay when they got their paychecks,” he said.

Former Pullman resident Anita Ferguson grew up just a few doors from the Lisciotto family and has fond memories of Americo and his wife, Maria. She was a playmate of their son, Lenny, and daughter, Cathy.

“We were kids in the neighborhood,” said Ferguson, who lives in Texas. “The neighborhood was Italian and Polish. You could walk down the street and hear both of them.”

Ferguson returned to her hold neighborhood for the tour with childhood friends and fellow Pullman kids Beverly Bravo and Denise Fattori-Alcantar. She said when she visited previously she noticed some homes were looking rundown, but that was changing.

“I’ve been pleased to see how the neighborhood was refurbished,” said Ferguson.

The efforts underway in the neighborhood are fitting for a place that’s one of a kind, Pat Shymanski said.

“Pullman was intended to be viewed as a comprehensive place, not just a house here and a house there,” she said. “Its uniqueness comes in its streetscapes and designs that were developed for the construction of the houses.”

Janice Neumann is a freelance reporter for the Daily Southtown.