John Herbert Dillinger arrived in the Chicago area in July 1923, for a respectable reason — he joined the U.S. Navy. But few knew the enlistment was an attempt by the machinist-in-training at Naval Station Great Lakes to beat an auto theft charge in Indiana. Or, that he would desert his ship, the USS Utah — and military life altogether — while it was docked in Boston just six months later. That left a dishonorable discharge on Dillinger’s record and set him on a course of violence.

The son of an Indianapolis grocer started by targeting what he knew best — a grocery store in Morgan County. When he was apprehended, Dillinger confessed to the misdeed at his father’s urging. Convicted of conspiracy to commit a felony and assault and battery with intent to rob, he was sentenced Sept. 15, 1924, to serve 10 to 21 years in an Indiana prison. His accomplice Ed Singleton, however, pleaded not guilty and was sentenced to just two years in prison. Dillinger was paroled almost nine years later. Embittered by his time behind bars, he took to robbing banks like a crooked Robin Hood during the Great Depression

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Dillinger and his gang (which included Lester “Baby Face Nelson” Gillis, John “Red” Hamilton, Harry “Pete” Pierpont and Homer Van Meter) terrorized the Midwest from September 1933 until July 1934. During that time they killed at least 10 people, wounded seven others and staged three jail breaks — killing a sheriff during one of them.

Dillinger ducked the authorities until 90 years ago this week. His Chicago whereabouts were given up by a woman desperate to clear her own name. Here’s a look back at how the Tribune reported the notorious gangster’s demise.

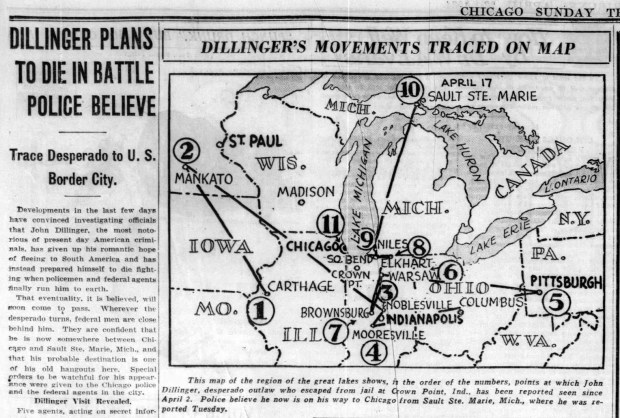

Dillinger’s travels

Dillinger’s love Evelyn “Billie” Frechette was arrested in Chicago during an April 9, 1934, raid and held on a $60,000 bond after the pair fled a March 31, 1934, a shootout with police in St. Paul. She told police Dillinger was also at the hotel where she was captured, but FBI chief Melvin Purvis “categorically denied” that.

As Frechette was flown back to St. Paul (where she would attempt her own escape) to face charges of harboring a criminal, Dillinger and his cronies were engaged in a shooting rampage with federal agents at a lodge by the Little Bohemia resort in the north woods of Wisconsin. Dillinger fled as two men were killed and four were wounded in the incident near Mercer, Wisconsin, leading some to criticize Purvis and his agency for their “criminal stupidity” in their failed efforts to bring the hooligan to justice.

As Dillinger sightings popped up around the Midwest, Frechette was convicted along with a Minnesota doctor and nurse who treated his wounds. She served two years in prison and took part in a “crime show” to teach young people about the futility of illegal misdeeds.

‘Lady in red’ drafts a plan with investigators

Anna Sage, nicknamed the “Woman in Red,” at the Sheffield Avenue police station in July 1934. Sage had been with John Dillinger when he was shot and killed by FBI agents outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago on July 22, 1934. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

Despite Justice Department rewards totaling $15,000, Dillinger had lived a relatively normal life on Chicago’s North Side. He often had dinner at the Seminary Restaurant at Lincoln and Fullerton avenues. He went to a Cubs game at Wrigley Field and pulled one of his trademark bravado stunts by saying hello to his lawyer, who was chatting with a police officer.

Dillinger’s new girlfriend was a red-haired waitress and prostitute named Polly Hamilton. Hamilton’s landlady Anna Sage, a Romanian immigrant originally named Ana Cumpanas and operator of a house of ill repute on the North Side, has gone down in history as the “Lady in red.” (We’ll explain why in the next item.)

Sage had befriended Hamilton and offered to trade information about the outlaw’s whereabouts to authorities to avoid deportation over her activities as a madam. Purvis said he’d see what he could do but made no promises.

July 22, 1934: Ambush

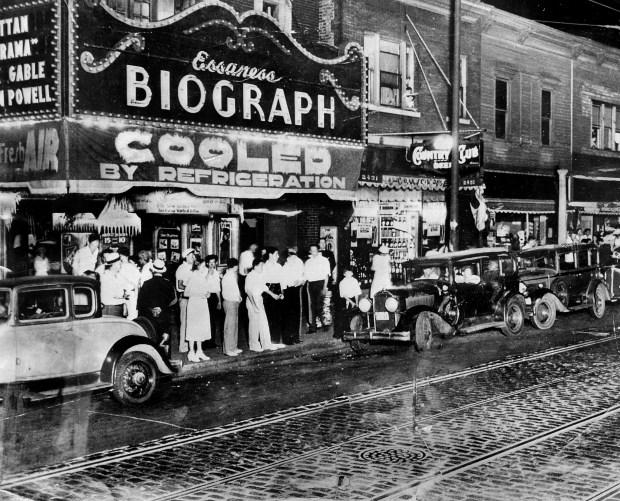

The Biograph Theater on Lincoln Avenue in Chicago around the time that John Dillinger was shot and killed nearby. (Chicago Tribune archive)

The city was in the grip of a weeklong heat wave, and the mercury that day had reached 101. Twenty-three people died of the heat on this date, but the death that drew the most attention was that of a 31-year-old Indiana man who, on his birthday a month earlier, had been declared Public Enemy No. 1 by the FBI.

In the heat of that July, movie houses advertised that they were “air-cooled.” Perhaps that’s what made Dillinger decide to take Hamilton and Sage to a movie that evening.

They went to Chicago’s Biograph Theater (now known as Victory Gardens Theater), 2433 N. Lincoln Ave., to see “Manhattan Melodrama,” a gangster movie starring Clark Gable. Dillinger was wearing a straw hat, white shirt, gray tie, white canvas shoes and gray trousers.

Outside the theater, about 16 federal agents and East Chicago police officers took up positions.

When the picture was over around 10:30 p.m., the trio left the theater and turned south on Lincoln Avenue in the direction of Sage’s apartment on Halsted Street. The artificial lights of the marquee made her orange skirt appear deep red — earning her “Lady in red” nickname.

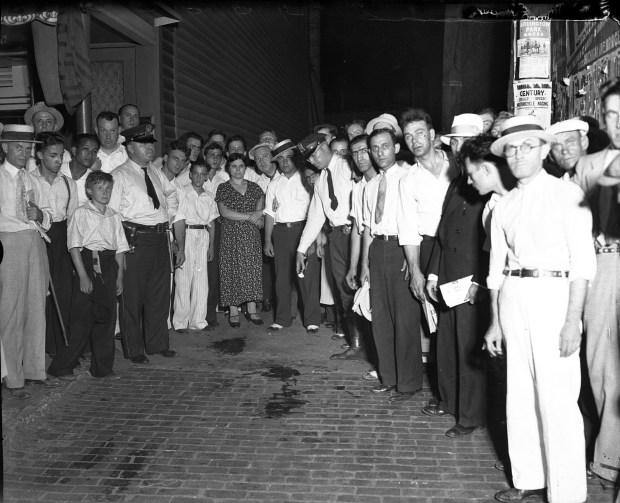

A crowd gathers around the blood stain from John Dillinger in the alley behind the Biograph Theater in Chicago in 1934. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

As the three walked south on Lincoln, Dillinger realized he was walking into a trap, pulled an automatic pistol from his pants pocket and bolted for the alley. Shots were fired . One bullet hit him in the back of the neck and exited through his right eye. That shot killed him. It apparently was fired by East Chicago police Sgt. Martin Zarkovich’s .38-caliber revolver. The weapon was bought by a San Francisco man at a 1998 auction for more than $25,000.

Thus came to end Dillinger’s long and infamous career in crime, including 11 months at the top of the country’s “most wanted” list. Souvenir seekers dipped handkerchiefs in Dillinger’s blood.

Sage got a $5,000 reward for her role, but not the deal she wanted. She was deported to Romania in 1936 and died there 11 years later. Frechette was still behind bars when Dillinger was killed.

The corpse with an audience

Betty Nelson and Rosella Nelson view the body of John Dillinger while in bathing suits at the Cook County morgue in Chicago. In the days after Dillinger was killed on July 22, 1934, massive crowds lined up outside the morgue to get a glimpse of the notorious public enemy. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

The 5-foot-7, 31-year-old man’s toe tags indicated that his was the 116th corpse brought to the Cook County morgue in July and that he was delivered by 37th District police on July 22. But this stiff was different — Dillinger’s body commanded attention wherever it went.

It was first taken to Alexian Brothers Hospital at West Belden and North Racine avenues, then to the Cook County morgue at West Polk and South Wood streets, where a crowd again gathered.

Another crowd, an estimated 5,000 people, gathered in the 4500 block of Sheridan Road in the Uptown neighborhood because people believed Dillinger’s body was there. Yielding to popular demand, officials allowed the people to come inside the morgue, in long lines that snaked down a flight of stairs to a basement room.

A July 23, 1934, story about the public reaction at the morgue opened: “‘There he is!’ These words were whispered in awed tones early this morning by a young woman, not more than 19 years of age, as she, with a dozen other persons, pressed her face against a ground level meshed window of the county morgue.”

Under the July 24 headline, “Throngs fight for glimpse of dead Dillinger,” the Tribune reported on the macabre, carnival atmosphere: “The Cook County morgue at Polk and Wood streets was a lively spot yesterday and last evening as crowds of spectators jammed in to get a view of the body of John Dillinger. For several hours they swarmed, pushing and shoving, down the steps leading from the first floor to the basement, where the body lay. Policemen shouted and members of the public shouted jovially back as they descended.”

The officials were in no hurry to close down this circus. When the undertaker hired by Dillinger’s family arrived to take the body, the coroner told him to come back the next day. “You can’t get near it now — too many curiosity seekers around,” he said.

The Tribune reported that people went through the line more than once, including one woman who said: “I’m disappointed. Looks just like any other dead man. But I guess I’ll go through once more.”

During the night, two layers of plaster of Paris were placed on his face resulting in a death mask. (Today it’s owned by Chicago businessman Ed Hirschland.)

Professor D.E. Ashworth lifts a plaster “death mask” off the face of John Dillinger while his students watch on July 23, 1934, at the Cook County morgue in Chicago. Ashworth, of the Worsham College of Mortuary Science, had told employees at the morgue that he had permission to create the mask, but he did not. Ashworth and his students were ousted from the morgue, and the partially completed mask was confiscated by the police. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

His body was left on display for another half-day before “six husky men picked” it up, and “forming a flying wedge, they pushed spectators aside and fought their way to the hearse.”

Dillinger’s body was driven to the bank robber’s small hometown near Indianapolis by his father and half brother and the undertaker. Once there, it was again put on display. The Tribune reported that “virtually the entire population of Mooresville, which totals 2,300,” viewed the body.

The burial ceremony at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis — which is also the final resting place of President Benjamin Harrison — was intended to be private but was marred by thousands of curiosity seekers and the roar of airplanes hired by newspaper photographers.

Even in his final resting place, Dillinger had company. Cemetery officials posted a round-the-clock guard to deter grave robbers and morbid souvenir hunters.

Dillinger: The enigma

The prolific crime writer Jay Robert Nash has argued in a pair of books — “Dillinger: Dead or Alive?” (1970) and “The Dillinger Dossier” (1983) — that Dillinger did not die July 22, 1934, most others do believe he fell dead and bullet-ridden in that alley.

In July 2019, the Indiana State Department of Health approved a request from Dillinger’s nephew, Michael C. Thompson, to have the remains dug up and reburied at Crown Hill Cemetery, according to officials. But the cemetery objected. Dillinger’s family filed but then dropped their lawsuit seeking the right to open his grave. Thompson is a frequent contributor to the Facebook group named The John Dillinger Died for You Society.

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com