Theaster Gates stared hard at a room full of furniture.

There were credenzas, chairs, desks, chests, a cube resembling an office refrigerator. Behind them, framed correspondence, photographs. Much of it came to him in 2010 after Johnson Publishing Co., home of Ebony and Jet magazines, vacated South Michigan Avenue. An office tower’s worth of furnishings, loose magazines, books, art and history needed a new home, and fast. Johnson Publishing was going through the final pains of watching its traditional place on newsstands vanish. So Columbia College stepped in and bought 820 S. Michigan. Johnson had occupied it since the early 1970s. It was the first building in downtown Chicago owned by a Black man. It’s still the only downtown skyscraper from a Black architect (John Warren Moutoussamy).

But Gates got a lot of the stuff from the landmark building. At least 15,000 objects in total, roughly 6,000 square feet of office ephemera, the majority of it from the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

Thinking of those frantic days when the building was closing, he smiled sadly:

“I am always thriving in decay.”

He said this in the lobby of the Stony Island Arts Bank near Jackson Park, the Prohibition-era savings and loan building he bought in 2012 for $1. Soon after, he raised the money, restored the imposing old bank for $4.5 million and turned it into a home base for the Rebuild Foundation, his innovative group that has, among other projects, created the Dorchester Arts + Housing Collaborative on 70th Street and the Kenwood Gardens on 69th Street.

Last week, for the first time, Gates began exhibiting a chunk of those Johnson possessions. Through March, it will occupy all three stories of the Stony Island Arts Bank, from the lacquered phone bank of the Johnson lobby to publisher John Johnson’s personal workout gear. Gates titled the exhibit “When Clouds Roll Away: Reflection and Restoration From the Johnson Archive,” mixing in his own works with a handful of pieces he owns by Kerry James Marshall, Ellsworth Kelly, Barkley Hendricks and others. It’s a stylish window into halcyon times, when magazine publishing exploded with life.

But the piecemeal dismantling of Johnson Publishing — Gates recalls it with a wince.

Then a shout.

“When the transition was happening, Johnson wasn’t shown in the best light,” he said. “The word ‘bankruptcy’ was used a lot. It was spoken of ‘being sold off in parts,’ that there was a ‘breakup of the company,’ and I remember thinking, ‘No one is also talking about its 70 years of Black excellence, its 70 years of Black dignity.’ We were just calling it a dinosaur that fell. There was little on the (expletive) good years! The way that John Johnson participated in the creation of Black wealth for so many across this country!”

He lowered his voice to whisper and said, “These are my personal feelings,” then got loud, as if wanting every assistant and staff member and visitor in the building to hear:

“But I wished this city could have given more to the Johnson legacy! So we could have immediately recognized that building as a historic landmark! Right away! And just gotten that (expletive) for whatever Columbia paid for it! Pennies on the dollar! Pennies! If we could have just cared more! Even if we didn’t know what to do with it immediately! The wealth of this city, they could have gotten together and said, ‘Here is the legacy of the first Black man on Michigan Avenue!’ Everything looked ripe for an amazing museum.”

He lowered his voice.

“And that perfect storm didn’t happen.”

He sat back in a red barber chair, John Johnson’s barber chair.

“Anything movable, we got,” he said. “But who wants John Johnson’s barber chair? How does one make sense of such an object? It’s hard to recognize this as valuable. It took years to parse all of it. But I have learned to see the value in gross accumulation.”

As you enter the Arts Bank now, to the right, there’s a small office vignette, a chartreuse footstool, leather couch, credenza, a crystal jar; to the left, a towering silo, constructed by Gates, containing hundreds of bound copies of Ebony, hardcover, color coded, sorted by decade, the spines of each displaying a series of lines from a poem by Gates.

In one room: John Johnson’s Fiat-size desk (lacquered).

On another floor: John Johnson’s 1950s belt exerciser, designed to jiggle way fat.

On the second floor: The entire Johnson Publishing library, cataloged, floor to ceiling.

Parts of the collection have been shown before, including the desk, at the Arts Bank, but not on this scale. Linda Johnson Rice — CEO of Johnson (who herself founded the influential Ebony Fashion Fair) — said walking into the exhibit “struck a major emotional chord.” She was reminded of her parents, her past, her professional future — all at once.

“What’s so exciting,” she said, “is how Theaster uses it to preserve the legacy of Ebony and Jet while simultaneously letting it live as a new form, for a new audience. You see the forward-thinking design, and my parents were major art collectors themselves, and here is it all reimagined by an African American artist they would likely supported, too.” The building, the interior design, its furniture, she said, “was all so far ahead of its time.”

Each of the nine floors of the Johnson Publishing Building was color coded. John Johnson’s floor was all red. The typewriter at the reception desk was covered in a red leather crocodile pattern. What we think of now as midcentury furnishings occupied most rooms. There were walls covered in wood from Africa. Visitors were greeted by a Richard Hunt sculpture, commissioned for the building. (It’s now on exhibition in Japan.)

The Ebony Test Kitchen — described once as “Afrocentric modernism” — went to New York City’s Museum of Food and Drink, then moved last year into the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Johnson’s massive catalog of photographs became a hot item at auction, and was inevitably acquired by Getty Images — though Gates, who had been outbid on the photos, was allowed to scan about 20,000 images and 35 mm film, mostly from Johnson’s archive of photos of women.

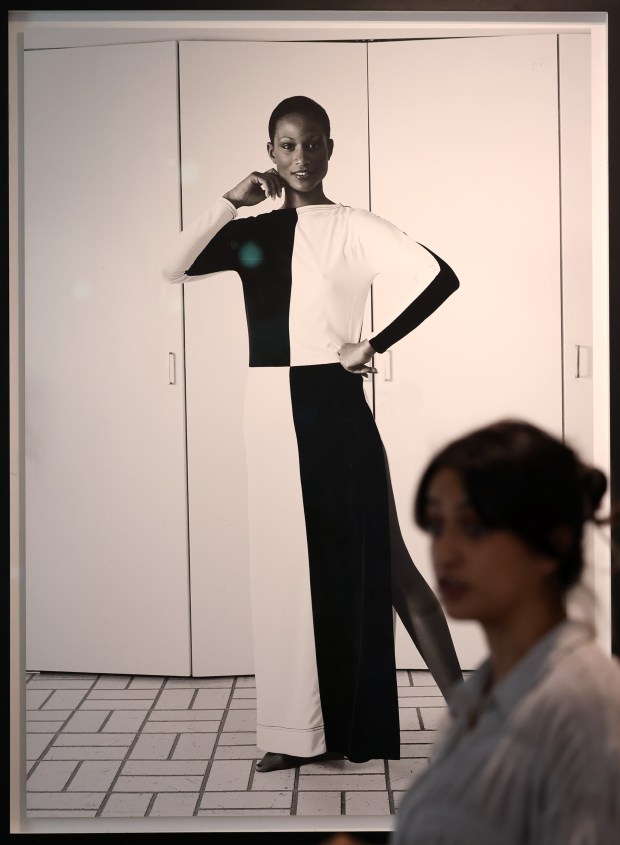

Those scans became the backbone of “Facsimile Cabinet of Women’s Origin Stories,” a long wooden installation, a peaked chest, containing about 3,500 photos, primarily made by Ebony’s Isaac Sutton and Moneta Sleet Jr. Visitors are invited to remove images (each framed in black wood) and arrange them on a shelf above the storage space. Photos of Black models, celebrities and performers, but also NAACP executives and businesswomen, children playing and everyday parents merely soaking their feet.

In the moments before Gates’ exhibit opened, Gwendolyn Hatten Butler, a longtime Chicago investor and financial director for a large array of institutions, brought Gates a framed 1990 Ebony article that featured Hatten Butler as one of the most influential Black business leaders in the country. It fit exactly into Gates’ need for the show to explain the way that Johnson Publications reflected a variety of everyday experiences.

“Look at you!” he cried, staring at the article. “You were fine! Still are!”

“That was two husbands ago,” she said with a laugh.

Hatten Butler said later that when she first moved to Chicago in 1977, she was an Ebony reader mostly because “their coverage of Black business was not only aspirational but gave me the confidence that I could pursue finance — and not only survive but thrive.” When she first went to the Johnson Publishing Building, however, she was struck by how “futuristic” it looked, how “floor after floor, they saw this office space itself as art.

“To see it now exhibited as actual art, that brings it full circle.”

Though Johnson Publishing launched in 1942, with a mission to chronicle Black lives as they truly were lived, it didn’t have a towering local building until 1971.

“My father saved 10 years just to buy that land,” said Johnson Rice. “There was nothing in the South Loop then. So everything about the building was done in an exacting way.”

Interiors were by famed designer Arthur Elrod, whose own Palm Springs, California, house was stylish enough to be featured in the James Bond movie “Diamonds are Forever.” Elrod, who had designed the Johnsons’ apartment, requested the job. (Johnson Rice lives there today.)

John Johnson died in 2005 at 87. Barack Obama, then a U.S. senator, spoke at his funeral. Five years later, the building was sold to Columbia College for $10 million; it has since been redeveloped by new owners into condominiums. Six years ago, it was finally granted National Historic Landmark status. Soon after, Ebony and Jet magazines were sold, while Johnson Publishing itself filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection in 2019.

Gates recalls scrambling to salvage what he could back in 2010.

“Linda invited me in, and I had 20 days and that invitation was loaded — you needed not only a place to store this, but the logistical knowledge of such important pieces. My studio team went in — plus hired guns expert at deconstructing so much beautiful shelving. So much was built into the architecture that you had to take large pieces of wall with you just to remove some things. You had to choose the cut to save the body.”

They even took wallpaper and carpet.

What followed was a dozen years of slow, expensive restoration. What’s on display at the Stony Island Arts Bank is just a sample. They have whole filing cabinets full of thank-you letters to John Johnson, by Harry Belafonte, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright. Those are not out.

Gates is already thinking of leaving some furnishings in place after spring, swapping in new pieces, permanently integrating Johnson Publishing’s legacy with his own. “Today it’s an exhibition. In six months, I’m hoping it’s more casual and lived-in, like a lounge.” Right now, he said, “it’s slipping back and forth between an art installation and historic presentation.” Not quite a museum, not quite an office, either.

“Eventually, it’ll be history in service to the present and future, and we’re getting there.”

“When Clouds Roll Away: Reflection and Restoration From the Johnson Archive” runs through March 16 at the Stony Island Arts Bank, 6760 S. Stony Island Ave. More information is at rebuild-foundation.org