I was at the Polo Grounds. I saw the New York Mets.

As Lloyd Bentsen might have said, the Chicago White Sox are no ’62 Mets.

By the numbers, the White Sox likely will be considered the worst team in modern Major League Baseball history, breaking the Mets record of 120 losses in a season. There is no real excuse. In sports, we live by that common dictum that you are what your record says.

I saw the expansion Mets regularly and I was at Guaranteed Rate Field often this season — and there can’t be many of us who can claim they did, or perhaps given the shared futility I should not admit it — but these White Sox were not those Mets. Not even close.

These White Sox mostly played professional baseball, if precipitously lacking in talent due to the makeover — OK, rebuild. There, I said it. Media would point to the occasional Keystone Kops antics like when three guys collided in left chasing a popup. (Yes, I am making century-old references now.)

But those were rare. There wasn’t enough pitching; 35 blown saves? I know it’s easy to pile on and fall back on the snark with a loser. I’m sure I did in the Tim Floyd days with the post-Michael Jordan Bulls. But it seemed like these Sox players cared and tried fundamentally and wanted to be taken seriously. They just weren’t good enough.

The 1962 Mets weren’t either, but they were a clown car from the start, and we all couldn’t be happier. I still know the “Meet the Mets” jingle by heart and despite six weeks of practice never could memorize Walt Whitman’s poem “O Captain! My Captain!” in seventh grade and failed.

We had a team again, after losing the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants. We could see Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Stan Musial, Ernie Banks, Orlando Cepeda, Frank Robinson and Willie Mays, the National League becoming far more dominant because of its embrace of the Black and Caribbean players the American League mostly avoided until the late 1960s.

The tone was set for me at the expansion draft when the Mets used the first pick for journeyman catcher Hobie Landrith. Manager Casey Stengel explained that if you didn’t have a catcher the ball would roll to the backstop every time. Stengel had led the Yankees through the glory days of the 1950s. He said he was fired because he reached 70 and he didn’t intend to make that mistake again.

And they were off.

The Mets had seven catchers that season, including trading for Harry Chiti for a player to be named later. It turned out to be Chiti, traded back to Cleveland as that later-named player. There was Marv Throneberry, a light-hitting lefty first baseman who’d had a brief stint with the Yankees. Not particularly light on his feet, there were regular adventures and he was embraced as “Marvelous Marv.” Once he tripled and was called out for missing second base. Stengel ran out to protest, but the umpire said Casey needed to relax because Throneberry missed first base also.

But we couldn’t have been happier.

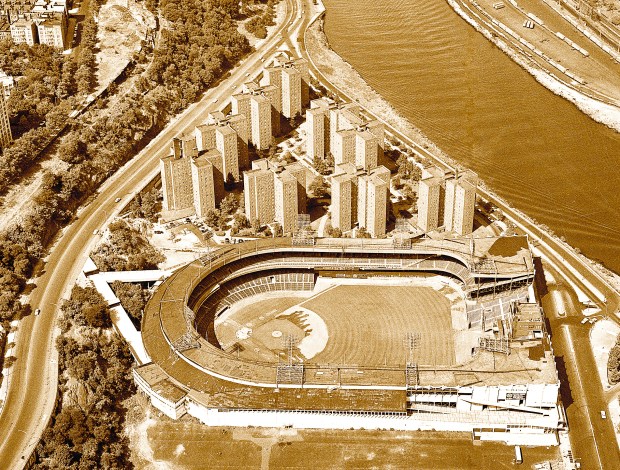

You didn’t go to the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan if you were from Brooklyn. The Dodgers traded Jackie Robinson to the Giants after the 1956 season, and he retired rather than play for the Giants. But now we finally got to see the famous dimensions, 250 feet down the lines where Dusty Rhodes had that pop fly walk-off to start the 1954 World Series sweep of the 111-win Cleveland team, and center field, where the locker rooms were, was more than 500 feet.

After the Dodgers snuck away, some of us migrated to the Yankees. The Giants were the rival; the Yankees were the patricians, like rooting for General Motors. But those were the Yankees of the Joe DiMaggio era. They actually were great fun in the ’50s, getting into bar fights most nights behind Billy Martin, and Mickey Mantle would have been the greatest player ever. He tore his ACL and MCL in the 1951 World Series and for his entire career, never getting it even diagnosed, was still the fastest player in the game and most powerful home run hitter.

We just couldn’t follow the Dodgers after owner Walter O’Malley’s treachery.

There was a joke told often in Brooklyn. You’re in a room with Hitler, Hirohito and O’Malley, and you have a gun with two bullets. Who do you shoot? Answer: O’Malley twice.

And then came the Mets.

Bill Shea was a lawyer and civic leader who led a committee to get a team after the Dodgers and Giants moved. It took him teaming with Branch Rickey starting a third major league, the Continental League, to get baseball to agree to an expansion, which became the Mets and Houston.

No one was pretending they’d be good. Shea said immediately they’d eventually get good players, just not yet. So for appeal, they signed a bunch of old Dodgers. Gil Hodges, Charlie Neal, pitcher Roger Craig, who went 10-24, and Don Zimmer. Former batting champion Richie Ashburn in his last season, and Marvelous Marv.

Forty-five players were on the roster that season.

It did continue for a while.

The Mets remained at the Polo Grounds for another season, and one of my favorites was in 1963 when a bunch of us were at a game and I was working hard to impress this girl who didn’t much know about baseball, explaining scoring and ancient concepts such as hitting behind the runner and bunting. I was feeling pretty proud of myself.

Then Jimmy Piersall comes to bat. No offense to DeMar DeRozan and Kevin Love, but Piersall was talking about mental health in sports 70 years ago. Of course, we weren’t very sensitive then. Anyway, Piersall hits a home run, turns with his back toward first base and proceeds to run all four bases backward.

“Why did he do that?” she asks. Heck if I knew. Turned out Piersall had told reporters when he hit his 100th home run he’d be running the bases backward.

The Mets moved to Shea Stadium in 1964 and began to take it seriously. They won the World Series in 1969 with one of the poorest hitting teams in baseball. But they built a brilliant pitching staff, which seems like what the White Sox are now trying to do. Remember, the worst-ever NBA team, the nine-win 1972-73 Philadelphia 76ers, was in the NBA Finals four years later.

No one is suggesting the White Sox will achieve success that quickly. But these things in sports are more layered than binary. You win, you’re a winner, and you lose, are you a loser?

Not so. The White Sox made all the right moves a few years back, and I kept reading about this potential Murderer’s Row of José Abreu, Yoán Moncada, Eloy Jiménez, Luis Robert Jr., Tim Anderson. They won a division and, well, we know what happened next.

Injuries, guys quitting, and well, you have to hit bottom. OK, maybe we didn’t think “core of the earth” bottom, but when you begin this process, as we’ve heard in the NBA, this is the result.

I saw the Sox taking it seriously, if not competently. Which perhaps is the greater indictment that they were trying to win. You just can’t do it with minor-leaguers.

Like Stengel said, without the losers where would the winners be?

Sam Smith is a former Tribune reporter and sports columnist. He covered the Bulls and NBA for the Tribune from 1987-2008 and now writes for bulls.com.