Of the many people whose lives still cast shadows on our history, one of them is that of a little boy, a 14-year-old named Emmett Till who left Chicago full of playful life and returned, as his mother, Mamie, said in 1955, “in a pine box, so horribly battered and waterlogged that someone needed to tell you this sickening sight is your son.”

I hope you know at least some of the details of that boy’s life. I have written about him before, many have, but there are good reasons to do so again, for it is now possible to meet him and learn his sad story in two powerful ways.

On Nov. 23, the Chicago History Museum is opening a new exhibition, “Injustice: The Trial for the Murder of Emmett Till.” It will feature photographs of the youngster’s life in Chicago, his funeral and original courtroom sketches of the trial.

That trial was a sham. Two men — Roy Bryant, owner of Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market and the husband of the woman at whom Till supposedly aimed his whistle, and his half-brother, a hulking, 235-pound World War II veteran named J.W. Milam — were first charged with kidnapping. That became murder after the teenager’s dead body was found.

Neither Bryant nor Milam testified during a trial that lasted five days. In closing arguments, defense attorney Sidney Carlton told the jurors that if they did not acquit Bryant and Milam, “Your ancestors will turn over in their grave.”

The all-white, all-male jury (nine farmers, two carpenters and an insurance agent) deliberated for only 67 minutes. Reporters said they heard laughter inside the jury room. The verdict? Not guilty. One juror later told reporters, “We wouldn’t have taken so long if we hadn’t stopped to drink pop.”

The outrage at the verdict was expressed in headlines across the globe, in part because more than 100 reporters were there, from Chicago, across the country and from Europe. One of them was future Pulitzer Prize winner David Halberstam, who covered the story for a small Mississippi paper. He would come to believe that the murder/trial were “the first great media events of the civil rights movement,” and “at last (could galvanize) the national press corps, and eventually, the nation.”

It should be noted that before the year was out, Rosa Parks, a seamstress in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. Arrested and fined for violating a city ordinance, this compelled a young pastor named Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to call for a boycott of the city-owned bus company.

Another person in the courtroom during the trial was Chicago’s Franklin McMahon, who documented the proceedings in drawings that appeared in Life magazine. His stunning art is among the highlights of the museum show.

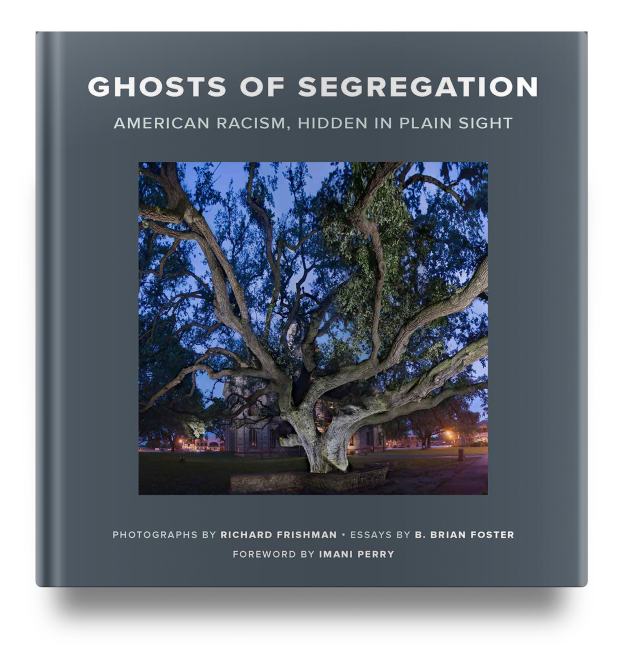

Know too that there is a new book that devotes some of its nearly 300 pages to Till but also to the larger sham of American racism. Its title says a great deal, “Ghosts of Segregation: American Racism, Hidden in Plain Sight” (Celadon Books). It is the work of former Chicagoan Richard Frishman, who traveled more than 35,000 miles across America over five years capturing with his camera such things as once-segregated bathrooms, beaches, churches, hospitals, graves and hotels.

In Chicago, he photographed the Dan Ryan Expressway; the Sunset Café, a prominent “Black and Tan” jazz club; as well as the site of the outbreak of the 1919 race riot. He also photographed Bryant’s Grocery, where Emmett’s story began, and the Black Bayou Bridge across the Tallahatchie River, where his dead body was found.

Frishman’s photos are captivating and thought-provoking. The book is beautiful in a haunting way and that was one of Frishman’s aims. In the book, he writes, “Look carefully. These photographs are evidence that structures of segregation and racist ideology are still standing in contemporary America. Our tribal instincts continue to build barriers to protect ourselves from people perceived as ‘other’ while overlooking our shared humanity.”

Critic Hilton Als has praised the book, writing, “Throughout (the book) the heart and mind are full to bursting with depth of feeling and depth of thought. I can’t imagine a more beautiful creation.”

When Emmett Till’s body was returned to Chicago, to the A.A. Rayner & Sons Funeral Home, with services held at the Roberts Temple Church of God, his mother made the brave decision to allow Jet magazine to publish a photo of the mutilated corpse and also decided to have a open casket, and so tens of thousands saw Emmett’s battered body. Some people prayed, some fainted and all, men, women and children, wept.

Now nearly 70 years later, Frishman tells me, “I am on a mission to open peoples’ eyes to the hidden and living legacies that surround us. History does not repeat itself; we repeat history.”

rkogan@chicagotribune.com