The harried search by the City Council and Mayor Brandon Johnson for ways to avoid raising property taxes — and in turn, the ire of their constituents — is leading them back to a question all too familiar in the halls of power in Chicago: Should they spare taxpayers financial pain and themselves political headaches now, even if it costs far more down the road?

Some officials are rallying around the idea of diverting surplus dollars from past years’ budgets that were set aside to keep the city’s pension funds afloat. The “advance” or “supplemental” pension payment Johnson wants for 2025 is $272 million, just shy of the $300 million tax hike he called for then abandoned last week in the face of an overwhelming council revolt against it.

Cutting that pension payment is among the most straightforward fixes floated to fill the gaping property tax hole in Chicago’s budget. But there are plenty of warnings against skipping it, including from Johnson’s budget team and municipal finance experts.

Among the potential outcomes they predict: Even bigger pension bills to pay later. Ratings agency downgrades for the city’s credit, making borrowing more expensive in the near term. A lingering budget deficit akin to this year’s $1 billion gap to fill in future years. Any of those outcomes would only add to the city’s — and ultimately, taxpayers’ — tab.

Politically, however, the $272 million is tantalizing. It would allow aldermen and the mayor to avoid the third rail of voting for a property tax hike, and also stay away from service cuts and layoffs that would draw immediate blowback from residents or powerful public sector unions. After his property tax increase fell unanimously Thursday in the council, Johnson told reporters Chicagoans don’t want cuts and he would not resort to firing city workers, but would not say what avenue he prefers to come up with the $300 million.

Regardless, the city will make its regular, required pension payments to its four funds in 2025, totaling roughly $2.6 billion.

“When you say supplemental it sounds like extra,” Chief Financial Officer Jill Jaworski said. But the city’s four pension funds are in such dire straits, the supplemental payments only help stop the bleeding, she said. Continuation of the smallish payments now would help shrink the city’s pension contribution tab by $3.9 billion through 2055, according to Jaworski.

Opting for more short-term fixes such as skipping this year’s property tax hike or using one-time revenues only means aldermen will be back at square one next year, with a structural gap to fill, Jaworski said.

Johnson’s budget proposal already relies on some one-time revenues, including a record surplus from special property tax districts around the city that will net $132 million and also offer some financial relief to Chicago Public Schools, which was at risk of sticking the city with an additional $175 million pension payment.

But those future carrots and sticks seem abstract to many aldermen who must face angry residents frustrated with rising bills. Compounding that worry are new property valuations mailed by Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi in recent months and the certainty that CPS — whose levy typically makes up half of Chicagoans’ bills — is raising its own property tax levy.

Though the city’s portion of the levy only makes up about a quarter of Chicagoans’ bills, aldermen and the mayor typically get the most heat.

Rising tax bills have been consistent, but not exponential in recent years. The median bill for Chicago homeowners stood at $3,811 this year, up from $3,285 five years ago and $2,575 a decade ago, according to data from the Cook County treasurer. The city’s median remains below the countywide median, $5,431. The jump for commercial properties has been more stark, with median bills nearly doubling from $6,646 a decade ago to $12,156 this year.

Median bills only tell part of the story, though, since increases can vary drastically between neighborhoods. Aldermen in gentrifying areas — including progressive mayoral allies such as Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez, 25th — have expressed some of the strongest opposition, but the pushback spans the ideological and geographical spectrum.

Sigcho-Lopez raced out of the City Council chambers just after Johnson introduced his spending plan to call for the advance payment to be cut. The Pilsen alderman has stood behind the call since and said Monday that Johnson’s administration had discussed with aldermen the possibility of making it smaller. He likened the choice to paying off a credit card or “putting bread on the table.”

And he’s not alone in questioning the additional 2025 payment.

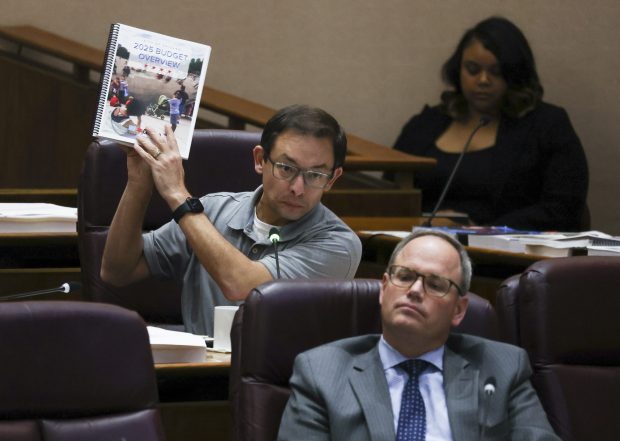

Ald. Mike Rodriguez, 22nd, who supports making the supplemental payment, made clear to the mayor’s team during hearings last week that others needed to be convinced. “You guys are going to have to make a great argument here to my colleagues on why (the supplemental payment) is important,” he said.

Johnson waved off questions about swapping out the advance payment early in the budget process, insisting he would not return to the “negligence” of past administrations.

“As much as we’re working to balance this budget in a responsible way, it is just as responsible to make sure that the retirement security for the people of Chicago is no longer questionable,” he said.

“This is me looking out for my children,” Johnson said. “I don’t want (my 10-year-old daughter) to have to worry about whether or not she’s going to be responsible for a debt that her father could have handled and dealt with when he was in charge.”

But with budget pressure mounting, Johnson’s finance team did acknowledge they had asked Aon to look at the impact of reducing the 2025 payment by 10%, 20%, or 30%. The city’s Department of Finance has an ongoing contract with Aon for actuarial services, benefits consulting and risk management consulting, according to the city’s contract database. A 30% “haircut” to the payment would save the city $81.6 million next year, but cost it an estimated $1.3 billion over the next 30 years, the mayor’s budget team said in a memo distributed to aldermen this week.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot established the advance pension payment policy in her final budget. Using roughly $700 million in surplus dollars left over from the 2022 and 2023 fiscal years, she signed an executive order designating the surplus be sent to the city’s pension funds on top of the more than $2 billion statutory payment already in the budget.

Even though the city had dedicated billions more to its pension funds since 2015, those contributions were still short of what the funds needed to tread water.

Instead, they sold off investments to pay out benefits. The Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund, for example, “liquidated portfolio assets by approximately $321.3 million, $366.3 million, and $471.1 million in fiscal years 2021, 2020, and 2019, respectively,” according to a city financial analysis from spring 2023. Selling off investments drives down funded ratios, only exacerbating the need for more money.

After aldermen approved the supplemental payment under Lightfoot, ratings agencies — which essentially provide grades so bond buyers can assess a city’s investment quality — applauded the move. The change triggered Moody’s to return the city’s rating back to investment grade from junk status, Lightfoot budget officials wrote in her outgoing forecast, saving millions in future borrowing costs.

The policy marked “a decisive shift away from an era where the city balanced budgets at the cost of a deteriorating balance sheet,” Moody’s wrote. The city estimated each bond upgrade saved $100 million for every $1 billion in borrowing.

Those same agencies are closely watching to see what Johnson and the City Council decide.

Chicago’s pension debt already makes the city an “extreme negative outlier” in the bond market, Fitch Ratings analyst Michael Rinaldi told the Tribune. Another Fitch analyst, Ashlee Gabrysch, likened the city canceling its advance payment to only paying the minimum on a credit card.

The decision would contradict the assumptions analysts have made to upgrade Chicago’s rating in recent years, Rinaldi added. “Skipping it in one year, it may signal that they sort of lack the commitment, sort of the fortitude to make those tough decisions, to stay the course,” he said.

The city’s current rating is “highly dependent” on making the payment, he added. “It could potentially get worse, which is hard to see, because it’s already a pretty dire situation.”

“Short-term thinking” caused Chicago’s pension liabilities to soar, Gabrysch said.

“Which essentially means that the city isn’t able to make investments, and new administrations aren’t able to necessarily fund their policy priorities, because there isn’t revenues to cover those additional spending items,” she said. “That is a choice that the city sort of makes explicitly and implicitly in deciding to make these short term fixes.”

To S&P Global Ratings, forgoing the payments is an “unsustainable budget practice that prioritizes short-term relief over long-term stability and could have negative credit implications,” lead analyst Scott Nees wrote in a statement. Moody’s Ratings has previously described cutting the payment as one of several “factors that could lead to a downgrade.”

There are two reasons rating agencies might frown on a move away from the advance, said Amanda Kass, an assistant professor in DePaul’s School of Public Service whose work has focused on public finance and pensions.

“The credit rating agencies look very favorably on the city putting extra money into the pension systems because it helps shore up the system’s finances faster. A move away from that is potentially a negative for the finances of the pension systems,” Kass said. “But another reason is the advance pension payment plan was using savings from 2022 and 2023 to make those advance payments. So if the city instead uses that money for other things in the budget, it’s using one-time revenue for recurring spending. It’s plugging a hole in a short term without addressing the structural imbalance.”

Kass noted the projected longer term savings are just that: projections. Liabilities are constantly recalculated to account for fresh costs, when investments rally or drop, or assumptions change. That’s what happened earlier this year: the city’s overall pension liability jumped to $37 billion because of the cost of a birth-date change in benefits for Chicago police and a change to how much the funds assumed they would get back from investments over the years.

Matt Fabian, a partner at Concord, Massachusetts-based Municipal Market Analytics, said given the city’s tight budget, it is constantly at risk of “downward pressure” from ratings agencies. But as long as the city makes its state-required payments, “I think we’re good,” he said. “The city has been on the right path. The extra payments that Lightfoot was making were good when the city had money. It doesn’t mean that you have to keep making them, either.”

Still, Fabian said it would be wise for the city to undertake “slow and steady” property tax hikes to both keep up with inflation and not shock the system. Key to that is showing the political conviction to stick with it. Lightfoot pushed through an inflation-tied property tax hike, but abandoned it in her final year in office. Johnson also skipped it last year.

Northwest Side Ald. Daniel La Spata said that when budget negotiations began he was in support of cutting down the advance payment. Now, he thinks there “isn’t a way around” making it in full.

“It sounds nice. It sounds like it makes sense,” La Spata said. “It isn’t worth what we think we would save.”