In 1968, José “Cha-Cha” Jiménez enrolled in a course to earn a high school diploma to fulfill a judge’s requirement after a 60-day stint in Cook County Jail on drug charges.

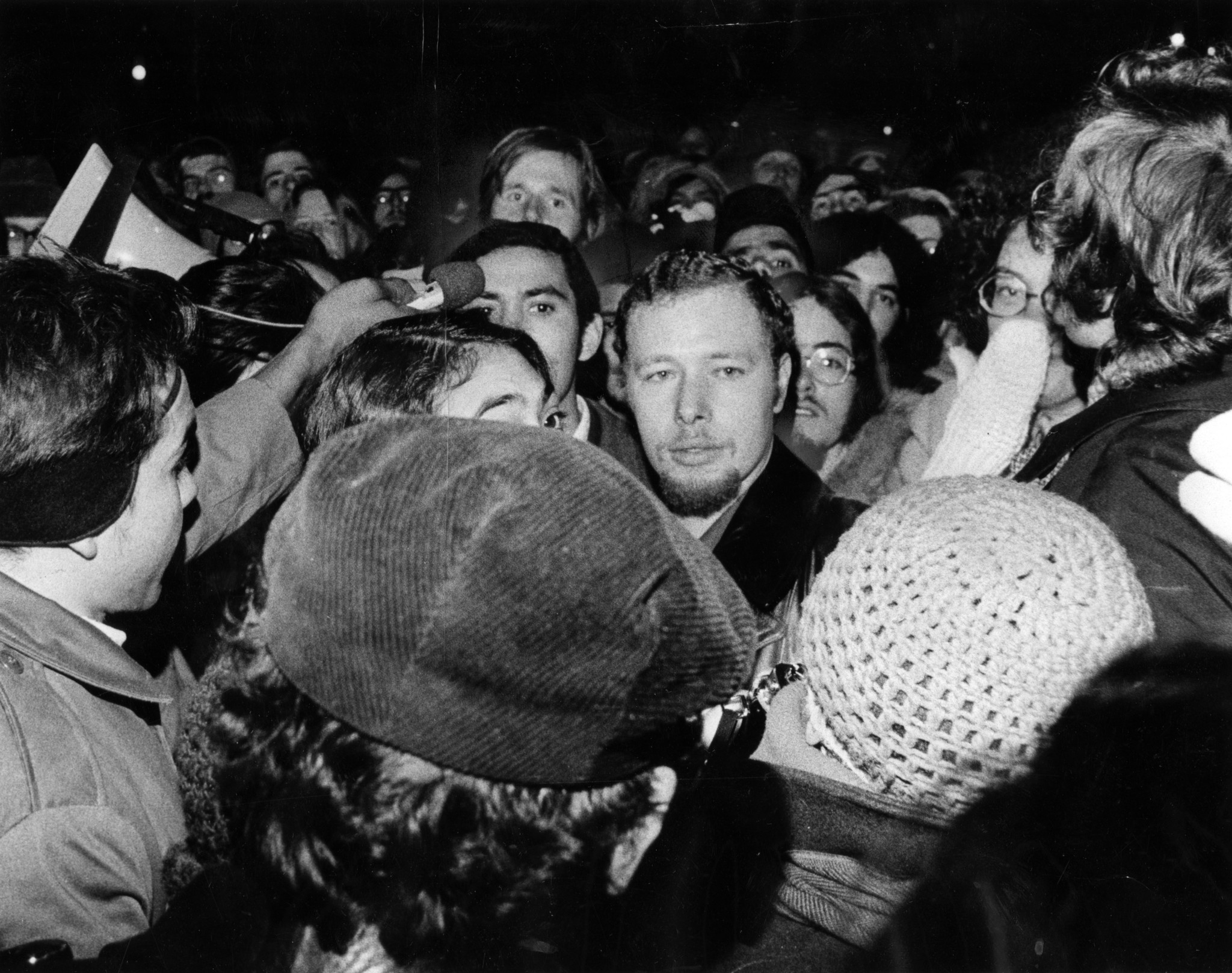

The teacher took the class to see the anti-war demonstrators drawn to Chicago by the Democratic convention that August, which both excited and confused Jiménez.

He could relate to young people taking on the cops, but he didn’t understand why they were cheering for the communist leader of North Vietnam. Overhearing Jiménez, a woman said she was a communist and invited him to a meeting of Chicago dissidents.

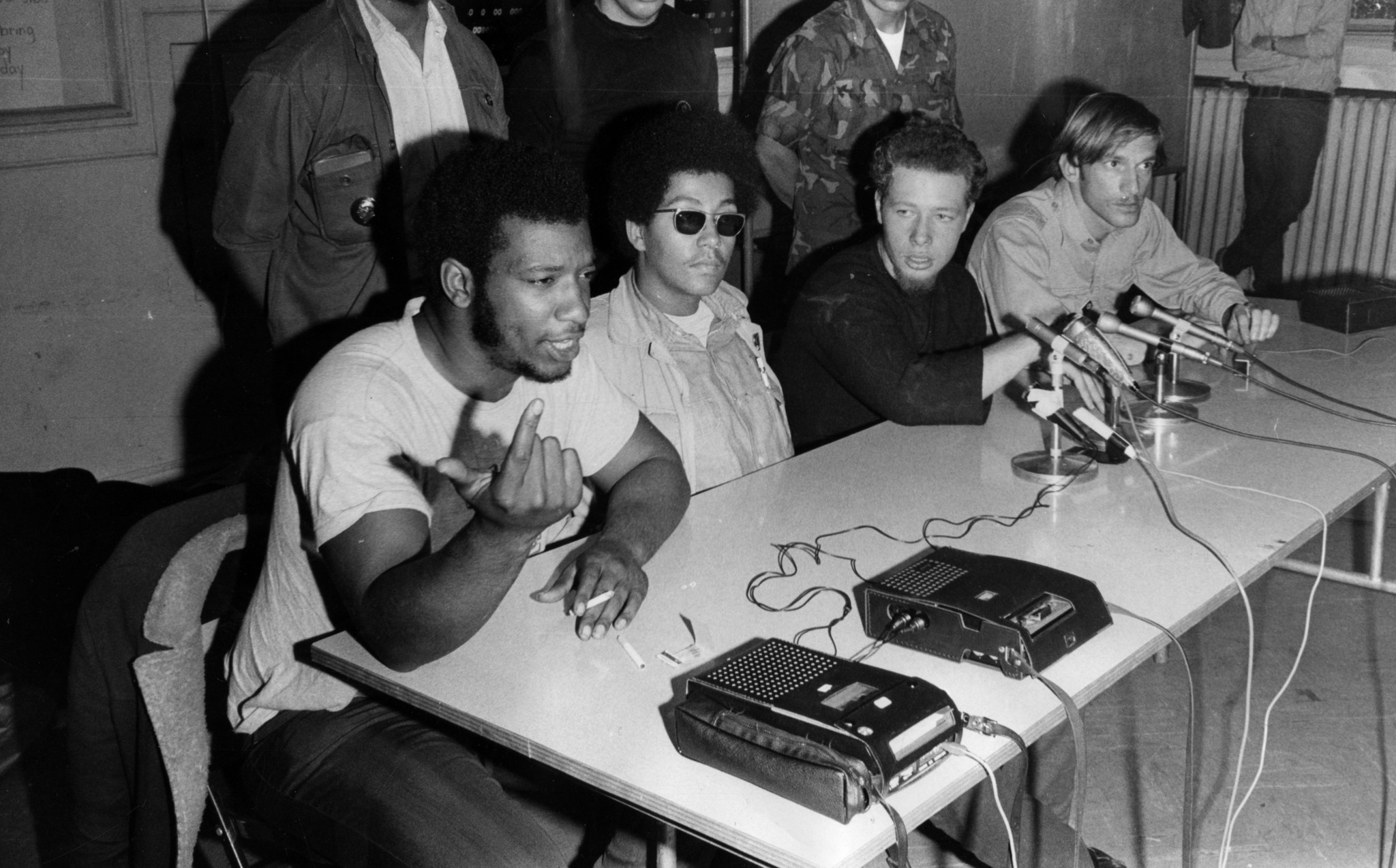

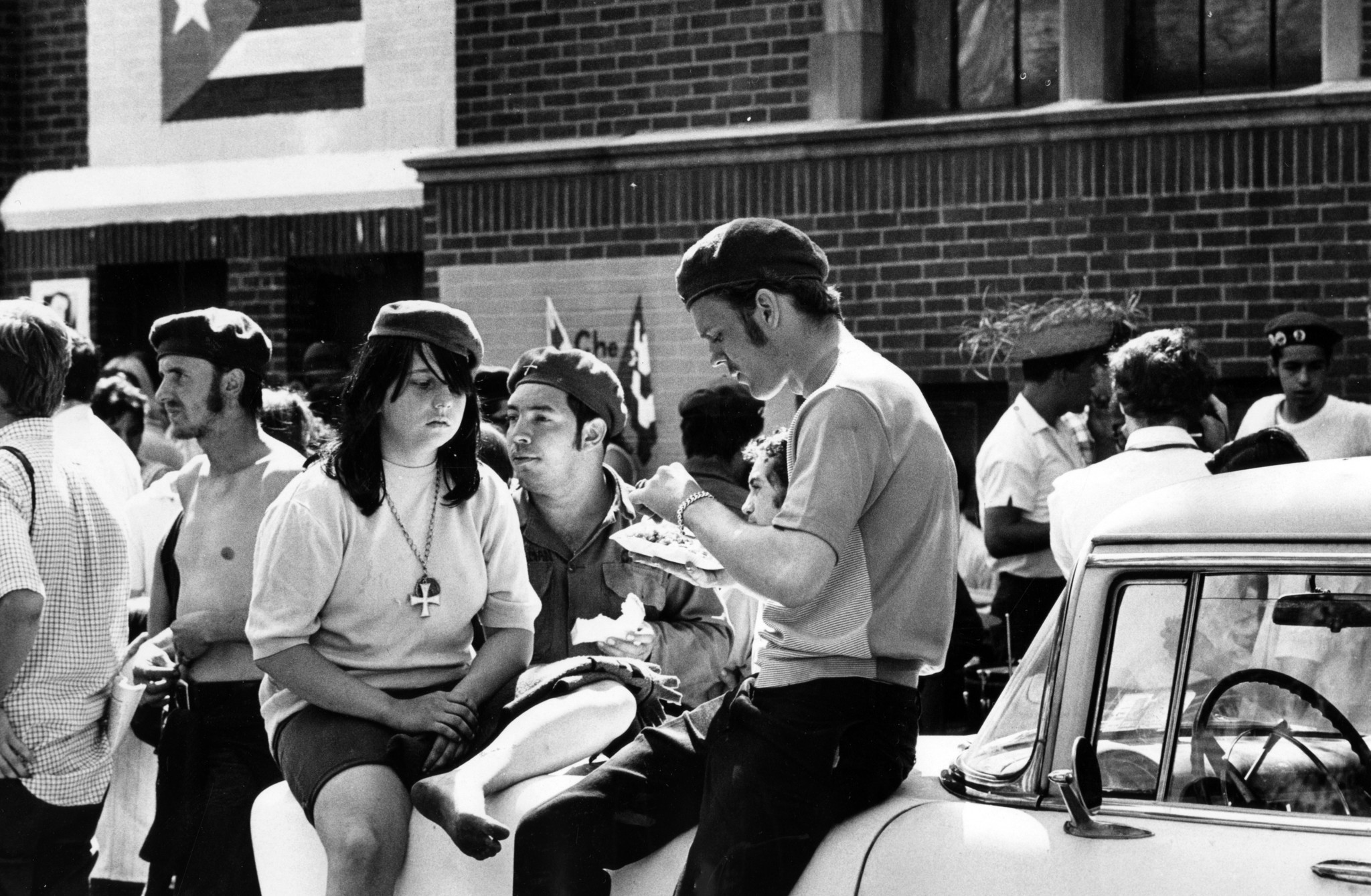

Jiménez — who in September 1968 re-established a Puerto Rican street gang in Lincoln Park called the Young Lords, transforming it into a political group modeled after the Black Panther Party that advocated for minority access to health care, education, housing and employment and expanded across the country — died Friday. He was 76.

His sister and caregiver Daisy Rodriguez announced his death on social media.

The high point of the Young Lords’ roller-coaster role in the turbulent politics of the 1960s and ’70s was Jiménez’s 1974 run for alderman of the 46th Ward. Afterward, they descended into obscurity, rarely credited for the voice, however fleeting, they’d given to a community silenced by poverty and isolation.

At the time of the Young Lords’ zenith, when Lincoln Park was one of the most impoverished barrios, or Spanish-speaking quarters, of the city, the group could “call a march” overnight and get 1,000 people to come out the next day, Omar López, the Young Lords’ minister of information and a longtime comrade of Jiménez, said Saturday.

In an era before cell phones and social media, the large response showed how good the Young Lords were at getting the word out.

According to the Library of Congress, the Young Lords was a multiethnic group inclusive to Black Americans, women and LGBTQ+ people. The activism of Jiménez’s followers drew recognition from Puerto Ricans across the country, and Young Lords chapters were established in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and other cities.

The group also rallied for Puerto Rican independence. Sept. 23, the day Jiménez re-established the Young Lords, was chosen deliberately because it was the anniversary of a 19th-century revolt against Spanish rule in Puerto Rico.

López said Jiménez was a leader who wanted to “defend” his community and began with the immediate issues facing it, which in Lincoln Park was housing.

“The Puerto Rican community was constantly being moved out and pushed out of neighborhoods,” López said. “And I think that was the first stance that he felt needed to be taken, and especially because it was affecting the families and the families of the members of the gang.”

Jiménez was born Aug. 8, 1948 — the same month as Fred Hampton, the Black Panther Party leader who was killed at age 21 in a Chicago police raid.

Before Jiménez’s move to Chicago as a child, his family lived in Michigan, where they worked as tomato pickers, López said.

“Before I finished the eighth grade, I was moved nine times by these developers and forced to attend four different elementary schools,” Jiménez recalled in 1974 when he ran for alderman.

While serving his 60-day sentence in Cook County Jail in 1968, Jiménez read books by Catholic mystic Thomas Merton and Martin Luther King Jr.

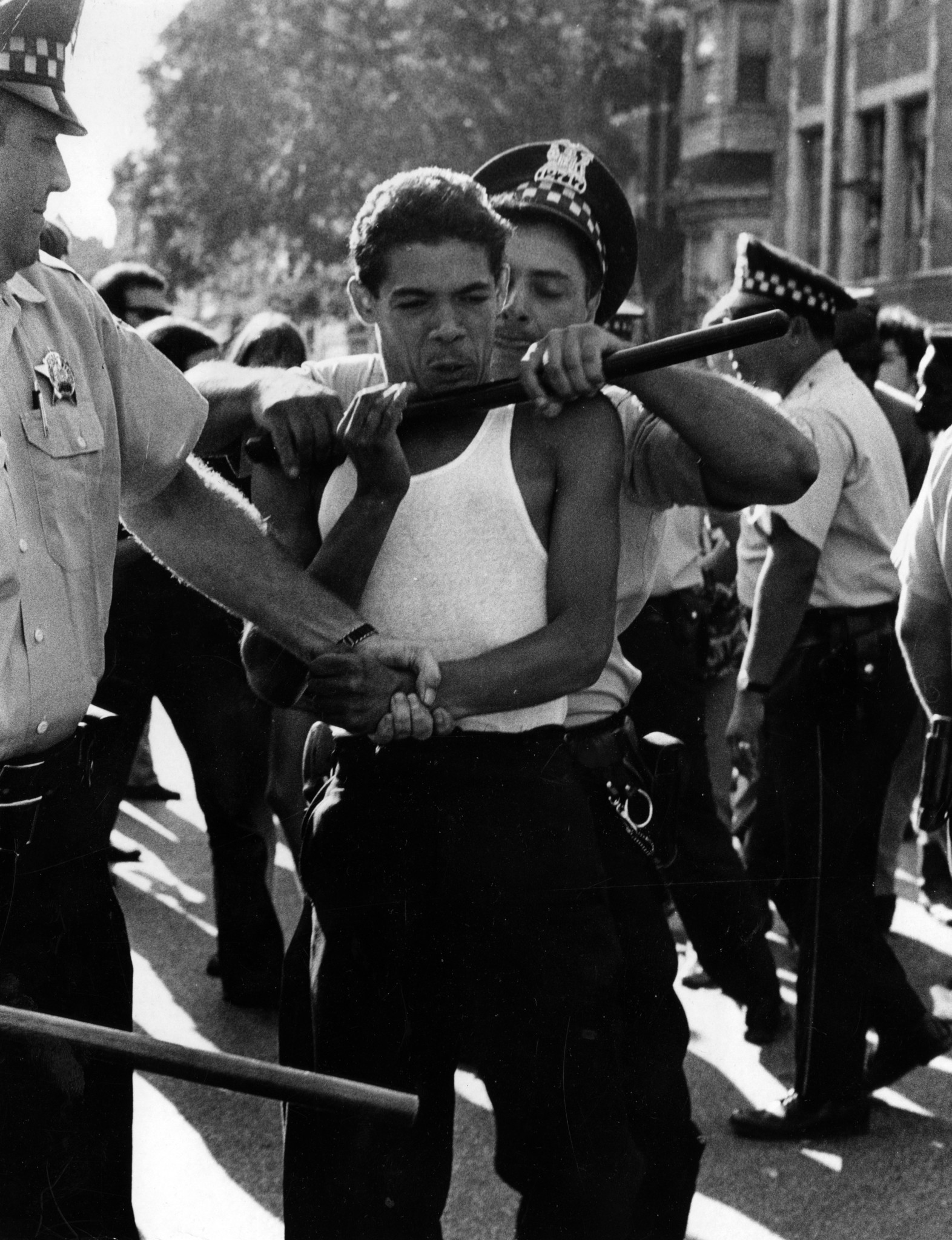

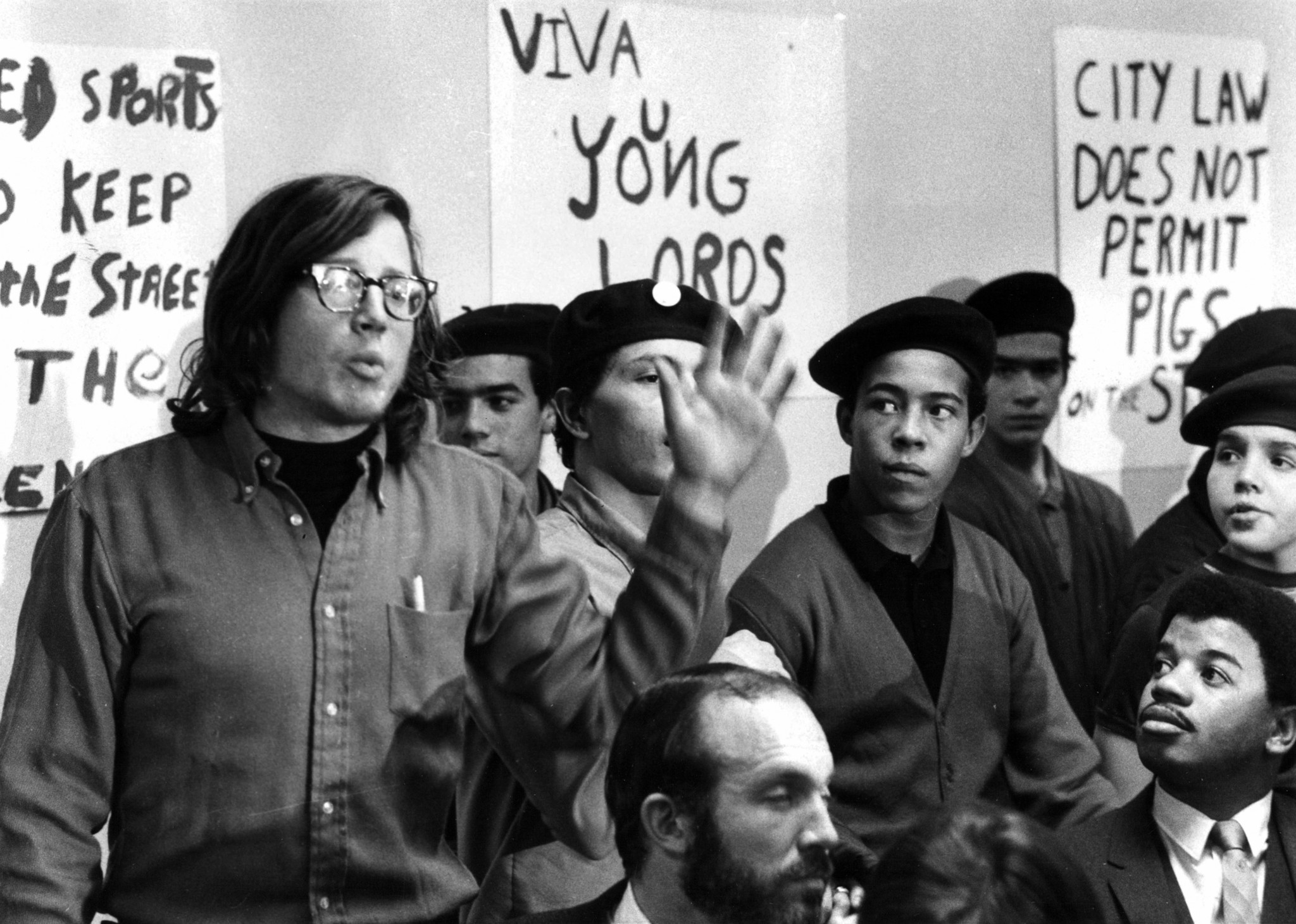

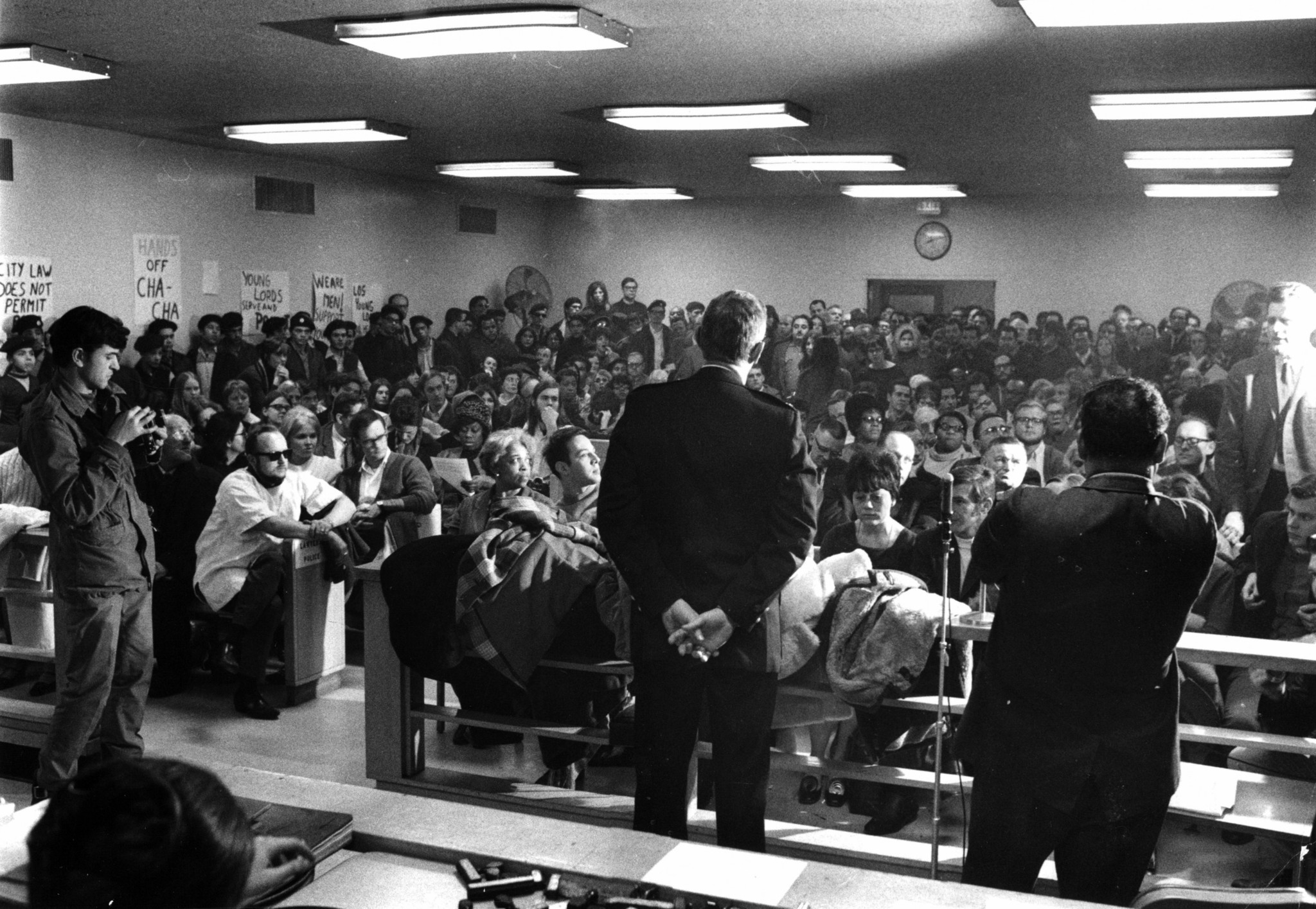

Shortly after the re-establishment of the Young Lords, known afterward officially as the Young Lords Organization, the group was imitating the Black Panthers’ confrontational tactics. In January 1969, the Tribune reported that the Young Lords threw chairs and yelled “Puerto Rican power” and “down with urban renewal” at a meeting of a group appointed by Mayor Richard J. Daley to supervise the redevelopment of Lincoln Park.

López, whose involvement in the group goes back to when it was a gang and who as minister of information oversaw all the propaganda that came out of the group, said the transition from gang activity to political activity didn’t happen all at once.

The May 1969 fatal shooting of a Young Lords member by an off-duty police officer during a controversial encounter, López said, was the watershed moment in his mind.

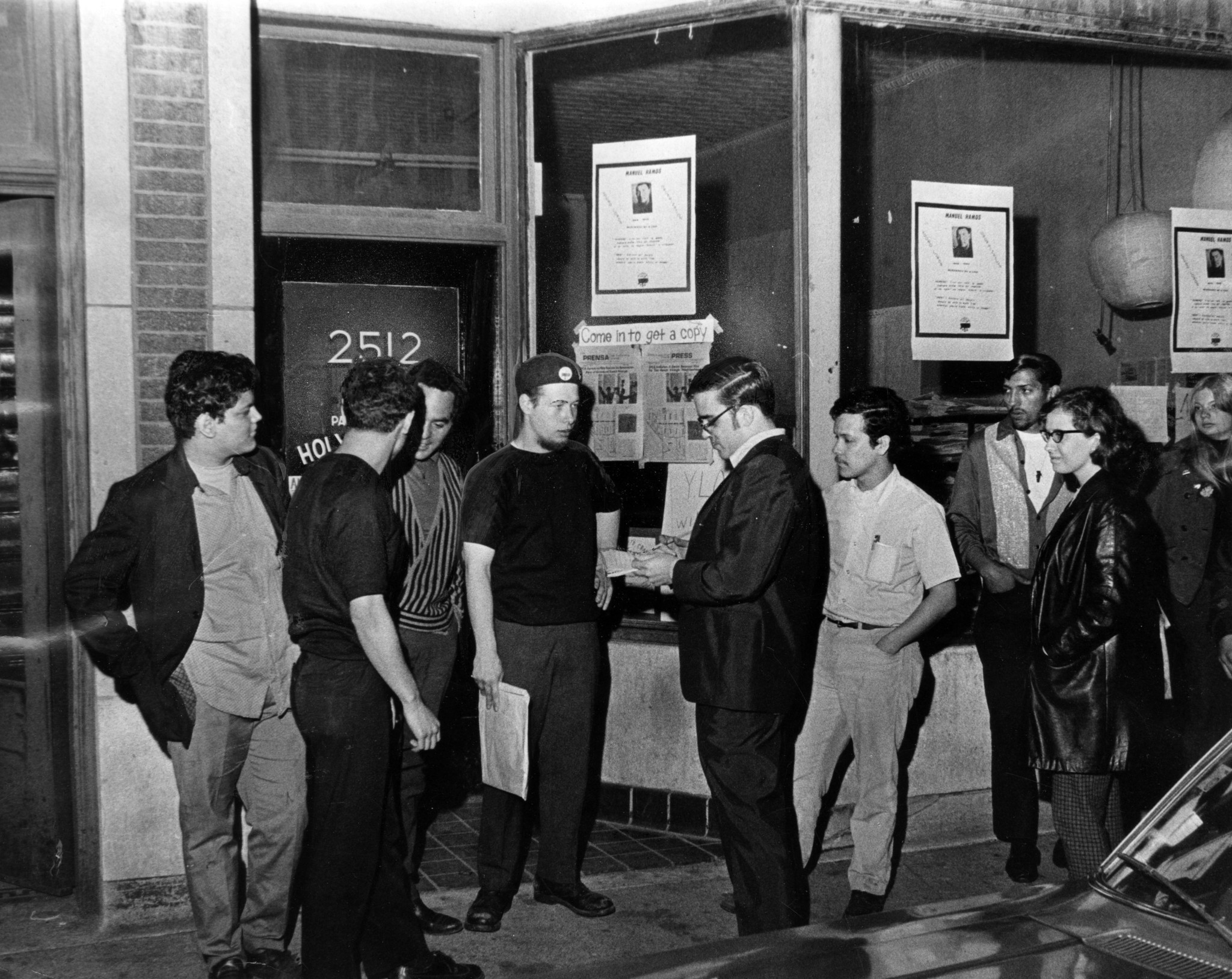

At midnight on May 15, 1969, a group of around 20 Young Lords marched into the administration building of McCormick Theological Seminary and demanded $601,000. The venerable Lincoln Park institution, at 800 W. Belden Ave., was renamed in honor of their slain member. Most of the intruders sported berets, which then marked radical activists.

After a several-day stalemate, the Young Lords left and the seminary agreed to negotiate with a “Poor People’s Coalition.”

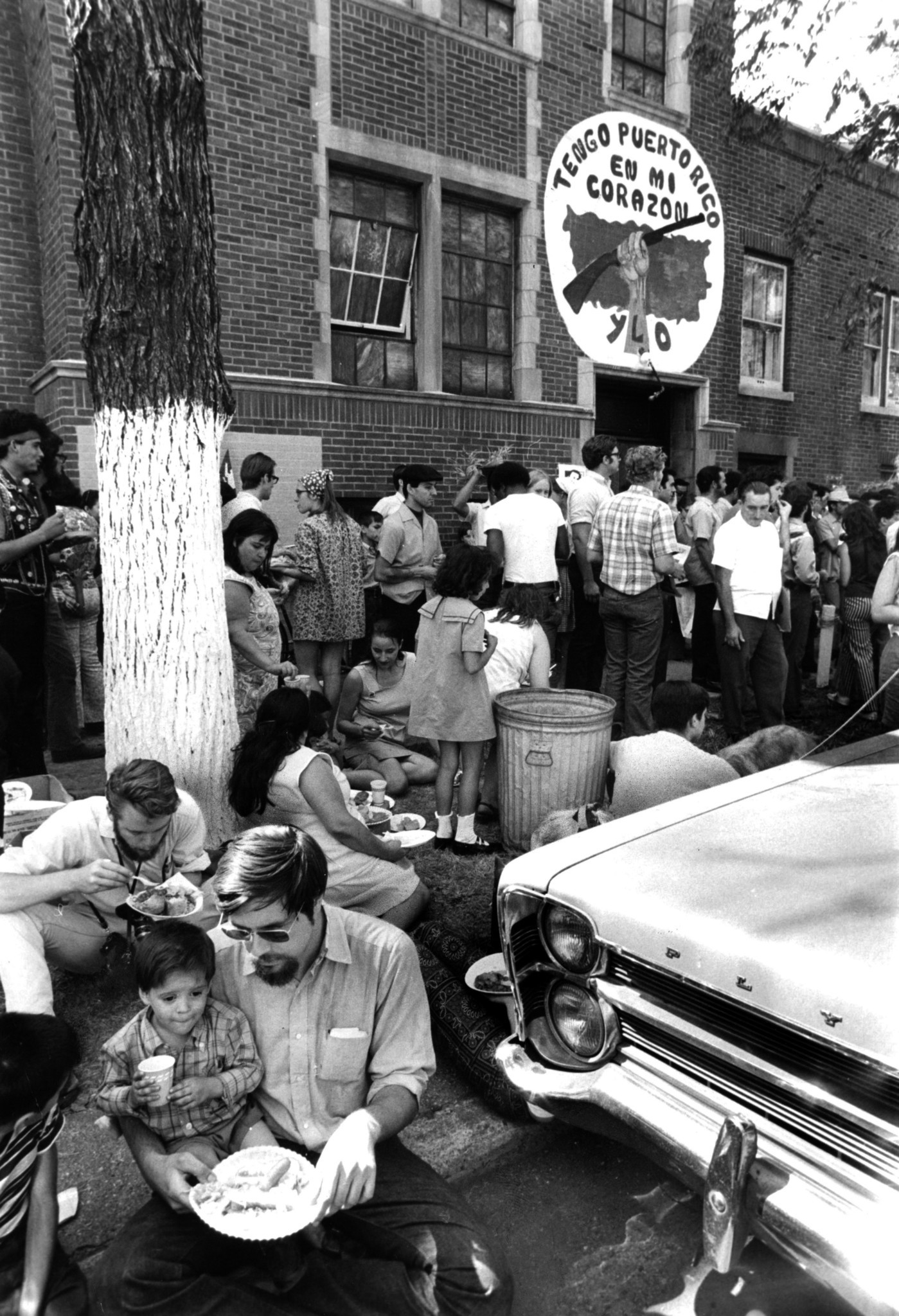

In June 1969, the Young Lords occupied the Armitage Avenue Methodist Church. Eventually renaming it the “People’s Church,” they immediately set up a day care center in the basement and later added a medical facility and a breakfast program for poor children. They also established a “People’s Park” on vacant land earmarked for development and organized tenants’ unions.

As the political group began to organize, it wanted to start addressing the community’s needs beyond housing, like health care, sustenance and child care, López said.

“In the process we were finding out that there was an entire system that was really in cahoots not to allow the Puerto Rican community to thrive in Lincoln Park,” he said. “And then as a result of that, the takeovers of McCormick Theological Seminary and the Methodist church (happened).”

López said he remained connected with Jiménez and talked with him a couple of months ago. During their conversations, López would refer to himself as the former minister of information and Jiménez would chastise him, saying the work of people like the Young Lords was still needed, López said.

“The organization doesn’t exist per se,” López said. “I think a lot of the members are still around, and they’re still active in different issues around the city here in Chicago — and around the nation. The spirit and the vision of the Young Lords is still alive.”

During a June 2022 ceremony, Jiménez passed the torch to a group called the New Era Young Lords, according to Paul Mireles, deputy chairman of Illinois for the new group.

“As long as we base our movements in love, we’re moving in the right way,” Mireles, 44 said Saturday. “And that’s what I get from ‘Cha-Cha,’ from the conversations I’ve had with ‘Cha-Cha.’ He had a lot of love and pride for the people in the community.”

In the fall of 2024, UrbanTheater Company put on a play telling the story of Jiménez and the Young Lords in Humboldt Park.

Rodriguez, Jiménez’s sister, shared on social media that a public visitation will take place from 3 to 8 p.m. Thursday at Pietryka Funeral Home on West Diversey Avenue.