The U.S. Department of Education has long been a target for government downsizers. Created by President Jimmy Carter to fulfill a promise to the National Education Association, it has faced calls for elimination since its inception.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan ran for president vowing to abolish it, but there was little support among congressional Republicans for doing so — until Donald Trump reignited the push for its dismantling. The DOE is the smallest Cabinet department with around 4,100 employees.

At first glance, the department’s future might seem uncertain, given Trump’s repeated promises to eliminate it and reports that he plans to sign an executive order to that effect — similar to his efforts to shut down the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). However, unlike USAID, the DOE is explicitly authorized by Congress and cannot be dismantled without congressional approval.

Democrats are claiming that closing the DOE would mean eliminating Title I and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) programs and other grant programs that, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, amount to around $30 billion in annual grants. While that is a significant amount, it equals less than 6% of what state and local governments themselves spend. Democrats also claim that Pell Grants, federal student loans, loan repayment and loan forgiveness programs administered by the DOE would also be abolished.

There is no indication that Trump intends to eliminate these programs. Even if he did, like any effort to dismantle the DOE, such actions would require congressional approval. That said, Title I and IDEA, along with numerous other programs, could be transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services, while the student loan program could be managed by the U.S. Treasury.

Many expect the White House to move the DOE’s Office for Civil Rights to the Department of Justice, arguing that this would weaken its ability to protect students against discrimination based on race, gender and disability. However, critics of the DOE contend that it has expanded its role far beyond its intended purpose and has promoted policies that limit state and local control over schools as well as parental rights.

Whether or not the Trump administration eliminates the department, the DOE’s priorities inevitably will shift. Maintaining the DOE under conservative leadership could allow for the expansion of school choice initiatives and greater parental involvement in educational decisions. Trump issued an executive order late last month, Expanding Educational Freedom and Opportunity for Families, which directs the DOE to prioritize school choice and expand the use of vouchers.

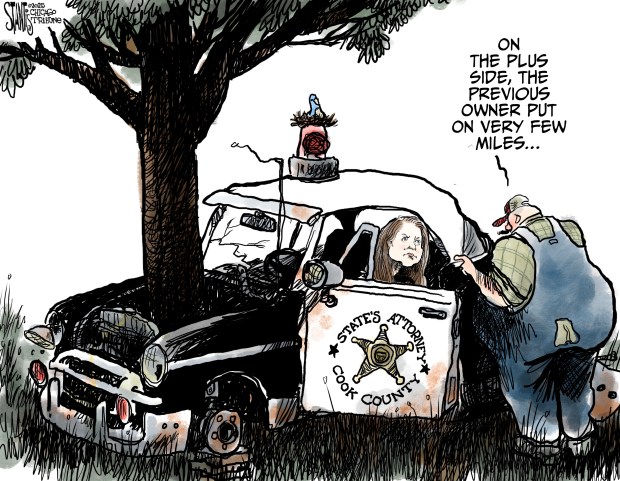

Frustration over teachers unions’ influence on the DOE has grown in recent years. Many low-income parents seeking alternatives to failing neighborhood schools have found little support from the department. The previous administration was criticized for policies that disadvantaged public charter and private school families, who are overwhelmingly Black, Latino and low-income, distributing federal COVID-19 relief and Title I funding.

Eliminating the DOE would certainly reduce federal interference in local schools, which escalated under Republican President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind (NCLB) initiative. NCLB mandated uniform math and reading standards and required states to make “adequate yearly progress” toward full proficiency by 2014. Democratic President Barack Obama’s Race to the Top program brought the country closer to a national curriculum, pressuring states to adopt Common Core standards and assessments.

Ironically, the same teachers unions now warning of disaster if the DOE is eliminated once aggressively opposed the department’s overreach. Unionized teachers even aligned with conservatives to block the Obama administration’s efforts to tie teacher evaluations to student test scores. Ultimately, NCLB was replaced by the Every Student Succeeds Act, which eliminated the adequate yearly progress mandate — the linchpin of federal control.

Restoring control of education to the states is not necessarily wrong or misguided. Federal oversight has often created bureaucratic obstacles rather than actually improving student outcomes. A more effective approach would be to hand over federal education funds to states in block grants with clear guidelines on how the money must be used. Meanwhile, the DOJ is far better equipped than the DOE to enforce civil rights protections.

Similarly, the Treasury is better suited to manage and oversee the federal student loan program. The DOE’s Office of Postsecondary Education primarily functions as a check-writing entity, facilitating the unchecked expansion of student loans while rubber-stamping accreditation bodies with minimal rigor — allowing all but a few colleges and universities to access federal funds regardless of their performance.

Any postsecondary programs deemed valuable by the new administration or mandated by Congress should be transferred to the Treasury, which can more effectively oversee taxpayer dollars. Taxpayer subsidies to higher education institutions that fail to serve students effectively should be reconsidered.

From its inception, the DOE was controversial — even among Democrats. Joseph Califano Jr., Carter’s secretary of health, education and welfare, opposed removing education programs from the broader welfare system, arguing that a stand-alone department would threaten higher education’s independence. Albert Shanker, longtime president of the American Federation of Teachers, also opposed the department, believing it would be ineffective and undermine state and local control of K-12 education. They were both right.

If the DOE’s primary objective was to improve education outcomes, it has failed spectacularly. Today, reading and math scores are near historic lows despite dramatic increases in funding. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, taxpayers spent nearly $190 billion in one-time federal education funding — on top of the almost $50 billion in annual DOE federal grants and almost $800 billion in state and local funding.

Real accountability is long overdue.

Paul Vallas is an adviser for the Illinois Policy Institute. He ran for Chicago mayor in 2023 and 2019 and was previously budget director for the city and CEO of Chicago Public Schools.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.