The city is pushing Chicago Public Schools to refinance about $240 million in debt to balance its budget for the year, a move that some finance experts argue is fiscally irresponsible.

In a briefing with reporters Tuesday, senior aides to Mayor Brandon Johnson said the district could get the money released out of an existing debt service fund, which school districts use to pay off debt similar to a mortgage or a construction loan on a house. CPS borrows money by selling bonds and has to pay it back over time.

CPS could then pay it back with expiring tax increment financing money — tax money set aside to spur growth in neighborhoods — in two to 10 years, Johnson’s aides said.

But the city and outgoing CPS chief Pedro Martinez are in a tough spot, financial experts say.

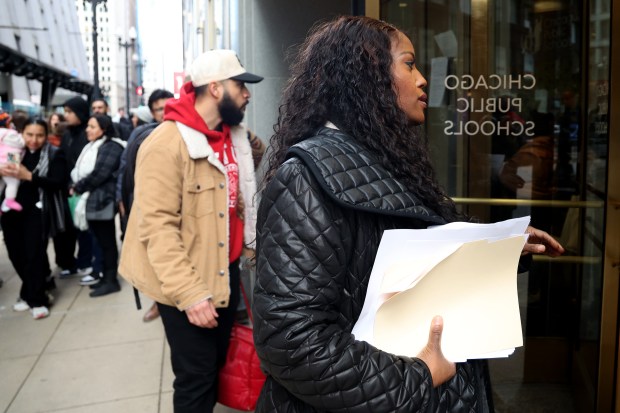

Due to a decline in federal funding and an increase in operating costs, the district is staring down a budget deficit of at least $500 million for the 2025-26 school year.

In a week, the school board will tasked with a difficult decision about how to balance its books. Board members have received advice from various financial firms and are waiting on another outside firm’s analysis to help understand the implications of that decision.

Six school board members told the Tribune they received an email at the beginning of March from the Board of Education’s bond attorney Lewis Greenbaum of Katten Muchin Rosenman warning against using debt to cover operating costs.

“We have reviewed the (Illinois) Constitution and applicable statutes concerning debt issuance by the District and we find no authority for the issuance of debt by the District to fund a budget deficit,” the email states.

Greenbaum’s email talks about the risks and challenges of borrowing under a budget deficit — where the amount of expenditures for the fiscal year is greater than the amount of revenues and reserve funds. Still, CPS’ proposal to restructure existing debt is different from issuing new bonds, according to financial experts.

Refinancing debt works in emergency situations, but the MEABF payment is less of an emergency so much as a “standard cost,” said Ralph Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability.

“It may get you through a budget cycle or two,” Martire said. “(But) it creates … fiscal stress that challenges your capacity as a public sector entity to continue funding your core objectives or services long-term.”

In July, Martinez settled the district’s budget without accounting for the costs of a $175 million pension payment for nonteacher staff or a new teachers contract. The mayor’s office acknowledged Tuesday that CPS is facing serious budget challenges this year, but said Martinez has committed to covering the Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund payment as well as the unsettled teachers contract.

The briefing with reporters came days after a budget amendment was posted online, part of the process for a governing body to account for those labor costs. Two budget hearings were scheduled for Thursday and Friday for the school board to hear from the public about how to best cover the gap, which Johnson’s top aides estimated to be around $240 million.

CPS began covering part of the pension payment five years ago as part of an effort to transition the district to an independent governance structure with a hybrid, half-elected, half-appointed school board, seated in January. District officials originally agreed to pay close to $300 million to the MEABF but Martinez negotiated the number to $175 million, according to the city.

CPS said in a statement that it has worked hard to minimize borrowing during the school year. Shifting funds to reimburse the city for a pension payment could increase the likelihood of cuts, furloughs, layoffs and a possible strike, district officials said.

“The district remains in a precarious position with no meaningful ability to use reserves or borrow for any budget gap closure,” a CPS spokesperson said in a statement.

Meanwhile, Jill Jaworski, Chicago’s chief financial officer challenged CPS’ bond attorney’s reservations on why it cannot take on more debt: “There is a manner in which they can come up with a plan of finance to do a borrowing, if that is fully necessary at the end of the day to meet their obligations to balance their budget.”

Asked for comment about the reservations, the mayor’s office didn’t immediately respond.

Complicating Johnson’s CPS agenda further is the looming exit of his top labor liaison, Bridget Early. The mayor’s spokesperson Cassio Mendoza on Tuesday confirmed her resignation, first reported by Crain’s Chicago Business, is effective at the end of the week.

Early’s official role — deputy mayor for labor relations — was created by Johnson on his first day in office as a nod to his administration’s focus on union outreach. But two years later, the inaugural job has been increasingly focused on one notable union: the Chicago Teachers Union, where Johnson cut his political teeth as an organizer.

After the mayor soured on Martinez over the MEABF pension and loan last summer, it was Early who served as a conduit between the mayor’s office and Johnson’s previous school board. The Tribune reported that in a Sept. 12 email sent to the board’s president and vice president, Early outlined a series of “talking points” on “board expectations from the mayor” for the rest of their term, including seeing the “CEO out by 9/26” and landing the CTU contract.

“It is okay if this is a lot to take on. If this feels like too much, we can work on an exit plan,” Early wrote at the end of her memo to Jianan Shi and Elizabeth Todd-Breland, who indeed resigned along with the rest of that seven-member board the next month.

Half a year later, Early is also heading for the exit, but without a CTU contract secured.

Martinez was fired without cause in December and is now presiding over negotiations as a lame-duck CEO until June, one that is actively working against the mayor’s $240 million CPS borrowing plan.

Early told Crain’s on Tuesday that the CTU contract is “nearing its conclusion.” But uncertainty abounds over whether the new hybrid school board has enough Johnson loyalists to shepherd his agenda over the finish line.

Previously the political director for the Chicago Federation of Labor, Early’s involvement in CPS matters makes sense given that CTU is one of the city’s most powerful unions and a top ally of the mayor. His previous deputy mayor for education, Jen Johnson, was the other top official in his administration with the most experience in that field as the CTU’s former chief of staff, but she stepped down in October.

Outside of that September memo to Shi and Todd-Breland, Early was in the room with the mayor during a November meeting at City Hall where Johnson allies chewed out Martinez over impending charter school closures. And last month, Early began disseminating a plan for the school district to accept the $175 million pension obligation and issue $242 million in bonds.

Public records obtained by the Tribune show that in the last couple months, Early also took the reins on corralling the hybrid school board — or at least part of it — on that endeavor.

Throughout February, Early met weekly with Johnson’s appointed board President Sean Harden and Vice President Olga Bautistia under the topic of “CPS BOE x MO,” her email records show. “BOE” stands for Board of Education, while “MO” stands for mayor’s office. In a Feb. 3 email to an executive assistant for the mayor’s office, Early wrote, “We do need these on a weekly basis for 30 minutes.”

Early also strove to schedule a weekly “Ed Meeting” with most of the Johnson-aligned members of the school board. Listed in the attendees across these check-ins are 10 of the mayor’s 11 appointees, with Cydney Wallace’s name missing as she was only brought onto the board in late February. At least two elected members who were CTU-endorsed were also invited: Jitu Brown, and Ebony DeBerry.

In total, six of the 10 members who were elected in November were backed by charter school interests or otherwise independent of the CTU. All of those members confirmed to the Tribune Wednesday they were not briefed by Early on the mayor’s CPS plan.

Board members will vote on the proposed budget amendment at a meeting March 20. Johnson needs two-thirds support from the 21-member board to pass a budget amendment, and the board president only votes in a tie. If the amendment doesn’t pass, that pension payment obligation will go back to the city. Johnson has until March 30 to balance his books.

In a post-City Council news conference Wednesday, Johnson refused to detail his backup plan if he loses the school board vote on his budget amendment. Instead, he all but accused Martinez of being dishonest if he succeeds in scuttling his CPS plan.

“I want to believe that the CEO did not come before the City Council and lie to them. I want to believe that,” Johnson said when asked what the city will do if CPS doesn’t absorb the pension payment. “You want me to answer that if the CEO lied to the City Council, what’s the contingency plan around someone being dishonest?”

Meanwhile, Johnson allies in City Council began collecting signatures for a message imploring Martinez to cover the MEABF payment during Wednesday’s monthly meeting. The letter carries no actual weight but has become a common mechanism for aldermen to exert defiance against the mayor’s CPS agenda.

Led by Ald. Jason Ervin, the mayor’s handpicked budget chair, and Jeanette Taylor, his education chair, the letter says they are “demanding CEO Pedro Martinez follow through on his commitment to the city of Chicago and reimburse Chicago Public Schools’ (CPS) portion of the MEABF payment.”

“We reject any attempts to pass the responsibility of balancing his budget onto the Council, or the taxpayers of Chicago, who we represent,” the letter says.

Martinez agreed to pay the pension payment at a City Council meeting in mid-October if he received $484 million in tax increment financing surplus money, allocated by aldermen after all funds have been pledged for projects within their district. CPS only received about $300 million in TIF surplus revenue when the district settled its budget in December.

Chicago Tribune’s Jake Sheridan contributed.