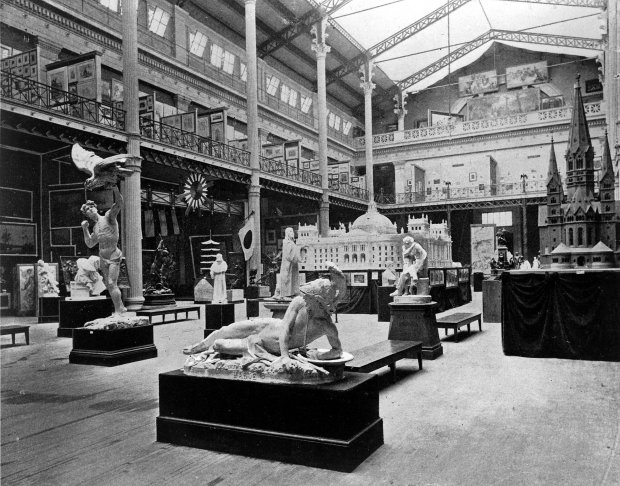

Once glorious, part of a shining showcase of classical architecture that became known around the globe as the White City, the bulk of the buildings that made up the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 had been emptied and abandoned after the World’s Fair closed in 1894.

Chicago bigwigs, many who’d been driving forces behind the fair, rounded up all the leftover exhibits and artifacts to form the basis of a museum that soon would receive substantial funding, and hence its name, from retail magnate Marshall Field.

Soon after, according to Chicago lore, the remaining White City structures burned down and that was that.

But that wasn’t really the end of the story, and some of the left-behind exhibition scraps may have contributed to another Midwestern phenomenon that had a global impact.

About 45 miles southwest of the World’s Fair’s Jackson Park site, a giant old barn is slowly decomposing along U.S. 52 just outside of the Will County village of Manhattan. Once part of a thriving livestock business, and then later a family hayride destination, the imposing structure now is the centerpiece of Manhattan Park District’s Round Barn Farm Park.

It’s not technically round, the barn has 20 sides. It was finished in 1898 and was supposedly constructed from wood salvaged from the World’s Columbian Exposition.

“That’s the story and people certainly stick to it,” said Jay Kelly, the Park District’s executive director. “We have no reason to believe it’s not true.”

In the years after the World’s Fair, treasures were consolidated in the former Fine Arts Building, now the Griffin Museum of Science and Industry. The Chicago House Wrecking company quietly moved in and began dismantling the fair’s skeletal remains.

“We prefer to go at the work with little publicity,” Chicago House Wrecking manager Maurice Rothschild told the Tribune in an Oct. 23, 1900 story about the company’s effort to secure the demolition rights to the 1900 Paris Exhibition in France.

“There are always people … who come to the fore with an outcry of vandalism whenever buildings of beauty and artistic value, like those of the World’s Fair and the Paris Exhibition are ‘wrecked.’ We have been troubled with incendiary fires more than once.”

The Paris Exhibition buildings, he said, were “on a more massive scale than were the Chicago buildings” and could net “at least 180,000,000 feet of lumber to be disposed of.”

Still the Chicago event’s haul “was a massive quantity of wood that came out of there, a phenomenal amount of material,” said structural timber expert Rick Collins, of Firmitas, a construction firm specializing in historic preservation projects.

The Galesburg-based company, which contracts on projects throughout the world, has “started to get a reputation for working on really big wooden buildings,” he said, including a slew of round and polygonal barns throughout the Midwest. That list includes the Littleton/Kingen Round Barn in central Indiana, which was damaged by a 2023 tornado, and another 20-sided barn in downstate Shelbyville.

The list now includes Manhattan’s Round Barn Park, where a $2.5 million renovation project is underway. Work on the barn itself is scheduled to start in April.

Collins said another previous contract involved a 12-sided church building in Morocco, Indiana, that had been built around the same time “and they had documentation they’d gotten lumber that was from the White City.”

In researching that project, he came across an old catalog from Chicago House Wrecking listing the materials available, much of it salvaged from the World’s Columbian Exposition. It was also built from the same “No. 1 doug fir free of heart center dense” timber he identified in the Manhattan structure.

“I never saw a lumber receipt or any documentation, but that’s the local folklore,” he said of the Manhattan connection to the World’s Fair. “If the material and timing fits together, then it’s a likely story.

“It seems like everything adds up, that it works.”

But even beyond the link to an event represented by a star on Chicago’s flag, the round barn is significant in its own right, Collins said.

“With polygonal barns, Illinois, Indiana and Iowa have the most in the world. Nowhere else in the world did this happen except the Midwest,” he said.

“The idea was you can use systems that were being developed during the Industrial Revolution — hay tracks and trolleys, different conveyor systems, movement of hay, manure, grain. Those came into play during the Industrial Revolution and you could no longer do things like that inside big, heavy timber barns. People tried to promote round and polygonal barns as the best way to use modern conveniences.”

Round and polygonal barns were marketed as being better suited to take advantage of machinery that would make livestock management easier, delivering hay from the upper levels to cows and horses in stalls ringing the walls below.

Manhattan’s huge, 20-sided barn was imposing — it’s the largest such structure in Will County and one of the largest in the country, according to the Park District. But Collins said it also represents “the industrial revolution’s reframing of how we viewed agriculture with machines — the first major change in agriculture since medieval times.”

“It’s a big deal,” he said, “not only for the Midwest, but it’s a big deal for the world. What the Midwest was doing in the 19th century shaped agriculture for the entire world for the next hundred years. What we were doing in 1890 in Illinois became the standard. It was the first move toward industrialized agriculture.”

Kelly, the Park District director, said the barn was primarily used for cattle for much of its early life, first by John Baker, who designed the barn and had it constructed. After a 1917 tornado damaged the barn and destroyed his farmhouse, Baker and his wife, Mary, died within two years, and the farm was purchased by Joliet doctor Arthur Lee Shreffler, who “was noted to have the best Guernsey herd in Will County,” according to Park District materials.

In the 1950s, much of the property was sold to Frank and Delores Koren, who in the 1980s transformed the farm into a recreational destination with a petting zoo, pumpkin patch, hay rides and museum. The round barn was converted seasonally into a haunted house. In the 1990s, the Korens led a successful effort to designate the barn as a Will County Historic Landmark. It was sold to the Park District in 2008.

“The barn is truly an icon to the region — Manhattan, Will County and beyond,” Kelly said. “For the people of this area, the Round Barn is very much a part of their lives. They worked at the farm or they visited the farm. People tell stories about ice skating out at the pond, or visiting the pumpkin patch.”

Shannon Forsythe, the district’s superintendent of recreation, said the story surrounding the deaths of the barn’s original farm family illustrates the impact of the Round Barn.

“A tornado in 1917 tore off the top level, and Mary and John passed away very shortly after it, it’s said, because of the heartbreak at the devastation,” she said. “To me, that’s a little heartwrenching, and it speaks to how much people have loved this place since the very beginning and up to now. You still hear it over and over again — everyone has a memory of being at the pumpkin patch as a kid, or maybe if they are older, maybe how they were working out there, about moving the hay around and how hard it was.”

Though never structurally at risk of collapse, the White City wood isn’t in great shape. Daytime sunshine leaks through chinks between boards and the building’s connection to its foundation appears tenuous in spots. The upper floors have long been off limits for safety reasons, and the barn itself was closed for a while.

Among the issues, Collins said, is the barn’s poured foundation “has led to a host of problems with the lower walls.” So the company will “lift it up and put a new foundation under it.”

“It’s pretty straightforward,” he said. “It’s not a lighthouse or a block in downtown Chicago. It’s a big building when you stand next to it, but it’s not as heavy as moving a brick house in Lockport.”

They’ll also reframe some of the walls and replace sections of purported World’s Fair lumber with rough sawn Douglas fir custom ordered from a West Coast sawmill.

If everything goes well, the work should be done by the end of the year, Kelly said.

The plan, he said, is to bring the barn up to code so it can be used for Park District programs and rented out for weddings and other events.

“Our number one goal is to preserve it for its historical value, but then to make it functional to the point where we and the community can use it,” he said.

It’s a rare resource, given that the era of round barns only lasted a few decades.

Collins said the same industrial forces that dotted the Midwestern landscape with round and multisided barns also made them obsolete. Factory farms gradually replaced many family farms; barns grew even larger and reverted to being boxy.

“By the end of World War II, agriculture has changed night and day from what it was when this was built,” he said.

His company, Firmitas, has done work on a wide range of structures, including a 1400s-era mosque in Greece. Manhattan’s Round Barn, he said, is just as important as that medieval structure.

“We live here, so we don’t think about it,” Collins said. “It’s important to the world. What was happening with agriculture here changed the course of world events.”

For Forsythe, of the Park District, the Round Barn’s impact is more personal.

“It’s all about the people who went before us, and what we can learn from them,” she said. “I’m in awe of these places that were built without power tools or any modern technology.

“We want to make sure people understand how people lived before, and what we can learn from them and the incredible feats they were able to accomplish.”

Landmarks is a column by Paul Eisenberg exploring the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at peisenberg@tribpub.com.