It’s clear within minutes of talking to Mary Margaret Rodriguez Decker that she may be 80 years old with more than her share of health issues, but this history-making politician and civil rights activist still has plenty of fight in her.

“I’ve had a lot of illness … I’m supposed to be in a hospital bed,” she told me on Monday, the morning after the Aurora Hispanic Historical and Cultural Foundation honored her at a presentation and reception at Casa Santa Maria on East Downer Place in downtown Aurora.

“But I’m a hustler. I’ve always been a rebel. It just comes natural to me. I know what’s right and what is wrong.”

After a couple minutes of reflection, Decker added, “I guess I’m also a history-maker.”

As the first elected Hispanic member of the Kane County Board – and two years before Cook County appointed Irene C. Hernandez as its first Hispanic county official – she is indeed a trailblazer.

Born in 1944 near the Mexican border in Crystal City, Texas, Decker came to Aurora at age 8, not speaking a word of English and a year after the arrival of her parents, who were founders of the Aurora Latin American Club and helped new immigrants settle into the suburbs.

So it’s no surprise that the young Mary Margaret Rodriguez would follow a similar path as a teenager, helping new arrivals get Social Security cards or jobs, not realizing at the time, she admitted to me with absolutely no guilt, that some of what she was doing was illegal.

After serving two years in the Army as a medical corpsman, she and new husband Stanley Decker – they met in the military – began raising their two children in Aurora. And Mary Margaret developed a highly successful career as the second Hispanic real estate agent and broker in the city, under the tutelage of Mary Lou Chapa.

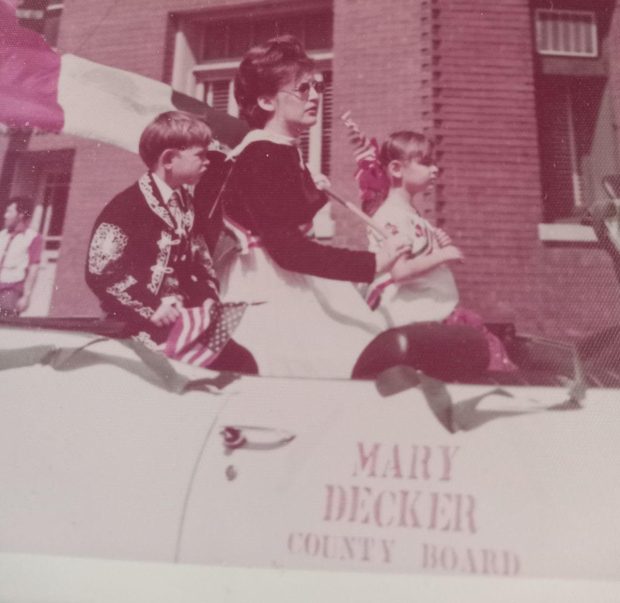

In 1972, upset with the way local leaders were paying little or no attention to the Hispanic residents of their community, 28-year-old Decker decided to run for the Kane County Board. Although there were three other Hispanics vying for the same spot, the mother of two young children counted on her light skin and Anglo surname to give her an edge in the race that, as both she and Aurora Hispanic Historical and Cultural Foundation President Alejandro Benavides insist, took place when racism was prevalent.

“Otherwise I never would have been elected,” Decker told me, pointing out a quote she gave to The Beacon-News soon after her victory that claimed the election results were “indicative of an ingrained prejudice. I with an Anglicized name, won, while Mr. Martinez and Mr. Plata lost.”

Decker proudly notes she’s never been afraid to say what is on her mind, which served her well on the Kane County Board as she continued to speak out on behalf of the Hispanic community. For example, Decker pushed for bilingual interpreters at government buildings and in schools. And she advocated for improved corrections and rehabilitation facilities. During her tenure, ground was broken on the new Kane County Adult Correction Facility that replaced the 100-year-old county jail.

Decker was also the first chair of the Aurora Latin American Citizens Committee, which focused on assisting Spanish-speaking people with problems concerning city and county affairs.

That group was created after the 1973 mass arrest of local Hispanics at the Hi-Lite 30 movie theater by U.S. Immigration agents, who had learned that the Montgomery drive-in had become a gathering place for Aurora’s growing Mexican population on Sundays because it showed Spanish-speaking movies.

According to news accounts, many were roughed up, and more than 80 were arrested or deported. Decker, who admits even today she’s “not afraid of anyone or anything,” led rallies attended by hundreds of protestors demanding justice, which garnered media attention from across the Chicago area.

Among the 50 or so invitation-only guests at Sunday afternoon’s reception was Juanita Wells, who recalled her eye-witness account of the event at the drive-in theater.

“I happened to be driving by. It was sad. Children were everywhere … it is similar to what we are seeing today,” Wells remembered, referring to the controversial ICE raids under the current White House administration

Benavides, a historical researcher and social activist with a doctorate in education leadership, says it was that drive-in raid – another occurred in 1997 with 62 arrests at the Aurora Dry Cleaners – when political activism in the area “began to rise.” As Hispanics became more empowered, they began to confront government officials, making more demands, including for economic opportunities, he added.

People like Decker, he told me, are the epitome of “historical resilience,” a term used to describe the ability of a group to withstand, challenge and demonstrate perseverance in the face of oppression.

According to Benavides, the Aurora Hispanic Historical and Cultural Foundation was founded last year after “much encouragement from people” following the ribbon-cutting ceremony honoring the landmark status of the C.B.&Q. West Eola Mexican boxcar camp and Austin-Western Historical Immigrant Working-class Neighborhood. After his book “Olivia: Boxcar-Camp Girl & Visionary of La Hispanidad” was published last year, he told me, more people suggested the creation of a Hispanic historical organization to focus on preserving and educating the community.

The story of Margaret was the foundation’s first event and was held last weekend in conjunction with the Mexican holiday Cinco de Mayo, a symbol of Mexican pride and identity.

“Margaret’s story is not over yet,” declared Benavides, referring to his colleague Antonio Ramirez, history professor at Elgin Community College who compiled the “Chicagolandia Oral History Project” with his students, and in doing so, stumbled across Decker’s story that he writes makes her “likely the first Latinx person to be elected to prominent office in Illinois.”

His project, according to Benavides, will be part of an exhibit, “Aqui en Chicago,” beginning Oct. 26 at the Chicago History Museum.

“I’m still on cloud nine” after receiving so much attention, said Decker, who stepped down after two years on the Kane County Board because of health-related mobility issues that made it hard for her to access the government building, which at the time was not handicap-accessible.

Now relying on a motorized scooter to get around in Crystal City, where she’s lived for the last 50 years, Decker told me she was determined to attend last weekend’s reception, even if it meant “coming here in my hospital bed.”

“My legs are weak. I can’t do anything about it,” she said. “My body is gone but not my mind.”

Decker seems genuinely humbled by all the attention she’s received as of late. But she also realizes that her story, her legacy, is important – particularly for young people who she views as critical in continuing the work local trailblazers began.

As Ramirez noted in his history studies, the Latino population, which has grown significantly, particularly in Kane County, is still vastly underrepresented in elected offices in Chicago’s suburbs and across the state, and that, just like in Decker’s time, their “voices struggle to be heard.”

Indeed, at the reception a passionate Cynthia Martinez, eighth-grade history teacher at Fred Rodgers Magnet Academy in Aurora and the 2024 Kane County Educator of the Year, lamented the low turnout of Aurora Hispanic voters in elections, which led to a discussion on what can be done to get more involvement.

Decker, who was brought to tears at this presentation, had a short but critical piece of advice for the impressive number of young people who came to see and meet the rebel lovingly known as “Magucha.”

“I did my part,” she said. “Now it is up to you.”

dcrosby@tribpub.com