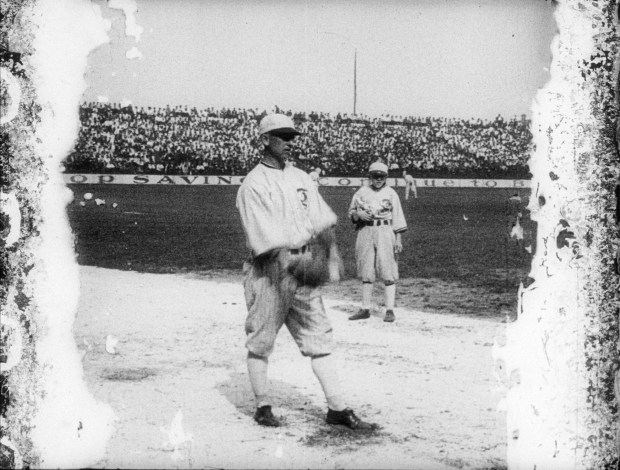

The 1919 Chicago White Sox — considered by some baseball historians as one of the greatest teams ever to take the field — were heavy favorites to beat the Cincinnati Reds in the World Series.

But in the best-of-nine series (Major League Baseball decided to expand from the best-of-seven format because of postwar demand), the Reds dominated.

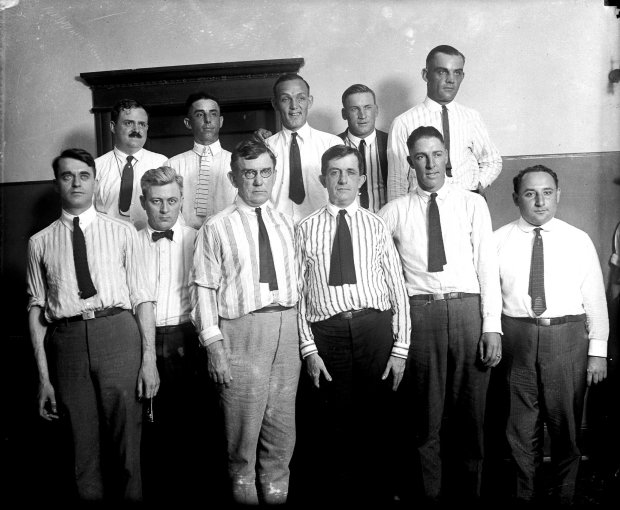

There had been rumors and reports that the fix was in, and indeed the Sox’s performance was suspect. A year later, eight Sox players were charged with conspiring with gamblers to throw the World Series.

In 1921, all were acquitted by a jury that deliberated for just 2 hours, 47 minutes.

A day after their acquittal, however, MLB Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis ruled the players allegedly involved — Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Happy Felsch, Chick Gandil, Fred McMullin, Swede Risberg, Buck Weaver and Lefty Williams — would be banned for life from organized baseball.

A century later, the team is still tagged the Black Sox. Here’s what to know about the scandal.

What happened during the 1919 World Series?

During the regular season, Sox pitching ace Cicotte won 29 games and slugging outfielder Jackson batted .351. So going into World Series, the Sox were heavily favored by the bookies.

They were offering 13-20 odds on the Sox, which meant a bettor had to put up $20 for a chance to win $13. Conversely, a $7 wager on the Reds would yield $10, which attracted the professional gamblers who don’t like leaving money matters to chance.

Game 1 demonstrated they were getting value for their alleged bribe money. It was played in Cincinnati, and the Sox lost 9-1. As the Tribune reported: “They missed hit-and-run plays twice in the first two innings, the very kind that they have been turning against the other American League clubs all summer, and the very kind of plays that have made the Sox such a strong offensive team.”

“I don’t know what’s the matter, but I do know that something is wrong with my gang,” Sox manager Kid Gleason said after Game 1. “The bunch I had fighting in August for the pennant would have trimmed this Cincinnati bunch without a struggle. The bunch I have now couldn’t beat a high school team.”

Here’s how the Tribune covered the whole series.

The Black Sox Scandal remains a popular topic for historians and entertainers, spawning books and movies such as “Eight Men Out” and “Field of Dreams.” But as the legend grew, so did the myths — such as that of owner Charles Comiskey being a miser, forcing his players to seek compensation through gamblers.

- How 8 White Sox players fell from grace and were forever marked the Black Sox

- 5 misconceptions about the scandal, including the myth about Lefty Williams and a hitman

- Flashback: Why the story of 1919 Black Sox scandal still resonates

What happened at the 1921 trial?

When the Sox lost the series, Comiskey acknowledged rumors that some of his players hadn’t been trying and offered $10,000 to anyone who could prove the accusation. He revealed he had hired detectives to investigate the alleged scandal.

“I am now very happy to state that we have discovered nothing to indicate any member of my team double crossed me or the public last fall,” Comiskey told the Tribune on Dec. 14, 1919.

Two weeks later, Comiskey walked back his assertion that there hadn’t been any monkey business. Then guilt pangs brought Cicotte to Comiskey’s office.

“Yeah, we were crooked,” the pitcher sobbed.

“Don’t tell me,” Comiskey said. “Tell it to the grand jury.”

According to Cicotte, the scheme wasn’t hatched by gamblers who seduced naive players, as it’s often said. His teammate Gandil was the architect. He recruited the other players and marketed the scheme to the underworld.

When the players were tried in 1921, Jackson repudiated his confession, and he and Weaver noted they had batted .375 and .324 in the Series, respectively. So the charge of throwing the series made no sense.

The jury acquitted them and the other defendants. But all eight players were banned from professional baseball by Landis, a Chicago federal judge who was newly installed as baseball’s first commissioner with a mandate to clean house.

What has changed since the ban?

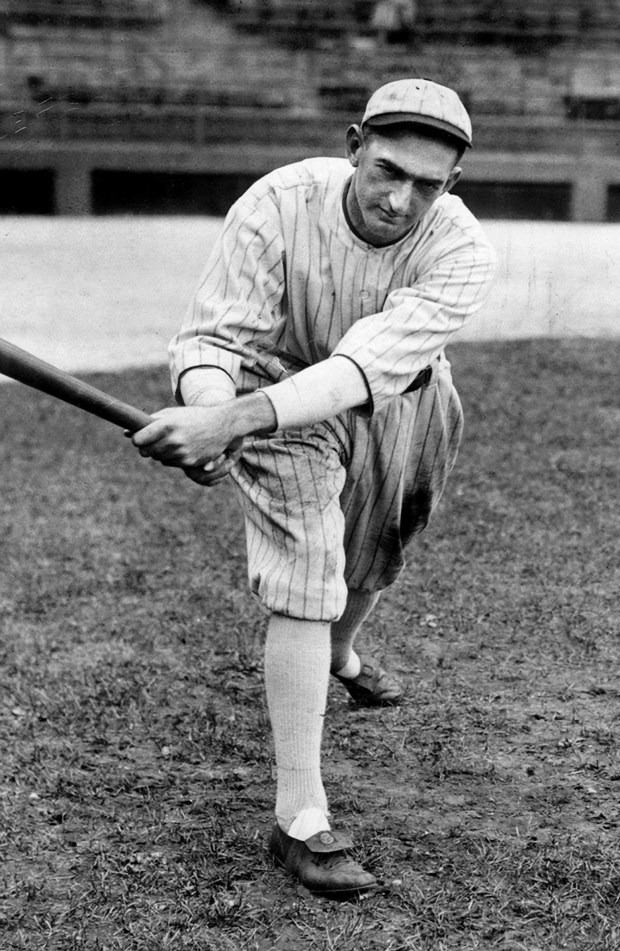

Commissioner Rob Manfred reinstated Jackson and the other seven banned Sox players — as well as MLB career hits leader Pete Rose — on May 13, making both Jackson and Rose eligible for the Hall of Fame.

Rose’s permanent ban, also related to a gambling scandal, was lifted eight months after his death and came a day before the Reds were to honor him on Pete Rose Night.

Manfred announced he was changing baseball’s policy on permanent ineligibility, saying bans would expire after death. Several others also had their status changed by the ruling, including former Philadelphia Phillies President William D. Cox and former New York Giants outfielder Benny Kauff.

Under the Hall of Fame’s current rules, the earliest Rose or Jackson could be inducted would be 2028.

The Sox issued a statement that with the reinstated players’ ability to be considered for the Hall of Fame, the team “trust(s) that the process currently in place will thoughtfully evaluate each player’s contributions to the game.”

Shoeless Joe’s legacy

To Jackson’s family, the punishment never fit the crime.

“The things that people get away with now, this is like nothing,” Debra Ebert, Jackson’s great-niece, said in 2019. “If someone would just listen to us …”

Mike Nola, a historian and board member at the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum in the ballplayer’s hometown of Greenville, S.C., said in 2019 there were no immediate plans for a new advocacy campaign.

But Nola said at the time that the board had recently heard that MLB or the commissioner’s office might not be the best direction for the long-shot remedy. He said that because all of the Black Sox players are dead, MLB might believe it doesn’t have jurisdiction over “lifetime bans” and that petitions or advocacy might be better directed toward the Hall of Fame.

“It’s not like if they reinstate Joe he’ll come out of a cornfield and play ball,” Nola said. “It just doesn’t work that way.”

- Commentary: ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson and me, an unexpected Black Sox tale

- 100 years after the Black Sox scandal, MLB — now aligned with a gambling partner — owes Buck Weaver and Shoeless Joe Jackson another look

Buck Weaver’s family’s push for reinstatement

For almost 30 years in 2015, Patricia Anderson had lived in a scenic, rural Missouri town about 100 miles southwest of St. Louis.

But in her living room, she was surrounded by images of her youth on the South Side of Chicago, where she was raised by her uncle — former White Sox third baseman Buck Weaver.

“Living with Buck, it was a wonderful way to grow up,” Anderson said. “He was my idol.”

In 2015, Anderson and her family launched their latest attempt to clear the name of Weaver.

“Pete Rose was a great player and we understand why baseball is considering his reinstatement,” said Sharon Anderson, Patricia’s daughter. “But our family can’t give up on Buck.”

Take a tour of local Black Sox landmarks

Chicago is home to many places associated with the Black Sox scandal to check out:

- Cook County criminal courthouse, 54 W. Hubbard St.

- Charles Comiskey’s grave, Calvary Cemetery, Evanston

- Ray Schalk’s grave, Evergreen Cemetery, Evergreen Park

- Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ grave, Oak Woods Cemetery

- Buck Weaver’s grave, Mount Hope Cemetery

- Site of old Comiskey Park