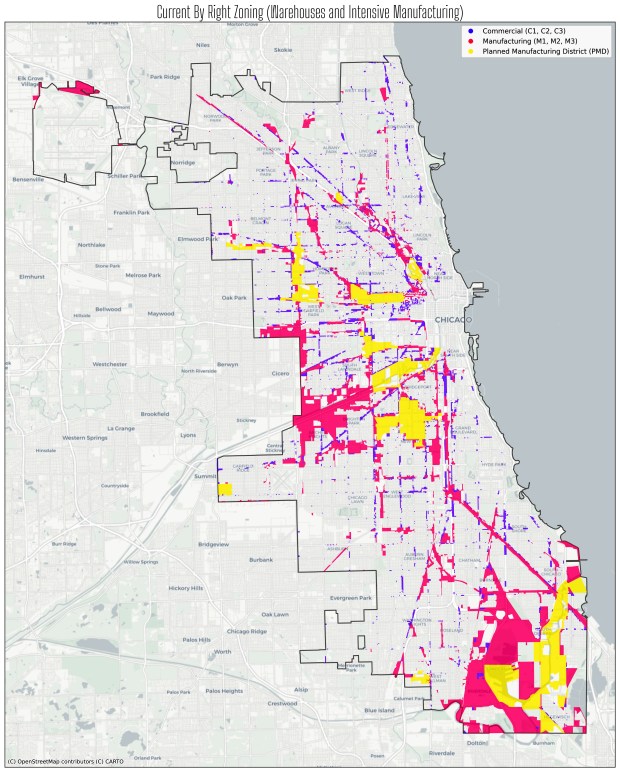

As communities are urging their representatives to support an environmental ordinance introduced in April to the City Council, a neighborhood group released maps showing large swaths of land across the city are currently zoned for commercial warehouses and industrial manufacturing that don’t require public notice or city approval to be developed.

Wards with the most land where this kind of use is permitted include the 10th Ward on the city’s Southeast Side, the 11th and 12th Wards on the South Side, the 25th Ward on the Lower West Side, and the 27th Ward on the Northwest Side.

“I was born and raised in the community, in Brighton Park, and we have a lot of manufacturing around our ward — and it was designed that way,” said Ald. Julia Ramirez, 12th. “The Hazel Johnson ordinance also considers the compounded impact that the community has already gone through.”

Named after the so-called mother of the environmental justice movement started over 40 years ago in Chicago, the ordinance would establish an advisory council to inform future environmental policy. Its main goal, however, would be to change zoning practices by requiring developers to study the possible cumulative impacts of a new project or an expansion, such as how it would affect public health in a community given already existing polluters, and meet with neighbors before applying for city approval.

It’s a tool, Ramirez said, to involve the community in decisions that will affect them.

“That’s the part that’s actually been missing from a lot of the discussions around development, up until now,” said Anthony Moser, board president of Neighbors for Environmental Justice or N4EJ, a grassroots nonprofit on the Southwest Side. “It feels very commonsense to me.”

The ordinance is the next step after the 2023 release of a cumulative impact assessment that analyzed how exposure to toxins, socioeconomic factors and health conditions vary throughout Chicago. That assessment was part of a voluntary compliance agreement negotiated with the federal government following a two-year federal investigation that found the city culpable of steering heavy industry away from white communities and into Black and Latino communities.

Currently, intensive industrial manufacturing of asphalt, corrosive acid, chlorine and insecticides, as well as warehousing, wholesaling and freight movement, are permitted in certain zoning districts. Under the ordinance, such developments would require special-use approval in those districts.

Moser said Chicagoans wanting to make relatively basic changes to their homes often need to obtain special zoning permissions.

“The idea that you don’t need any kind of permission to start a project that’s going to affect the whole neighborhood — I think, if ordinary people can deal with it, (developers) can too,” he said. “It’s not like this is suddenly going to prevent anything from being built here.”

When introduced to the City Council in April, the legislation was referred to the Committee on Committees and Rules, which has stalled hearings and voting, and will likely delay a review process that already takes months. Even after the ordinance passes, the city’s Departments of Public Health, Environment and Transportation still have to figure out what Moser called “the nuts and bolts” of the cumulative impact studies.

While 22 of the city’s 50 aldermen have reportedly expressed support for the ordinance, advocates say they’ll need at least four more votes to pass the bill. Strong proponents besides Ramirez include bill co-sponsor Ald. Daniel La Spata, 1st; Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez, 25th; Ald. Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez, 33rd; and Ald. Maria Hadden, 49th, who is also chair of the Environment Committee.

“If I were them, I would be thinking about it as a measure to mitigate political risk,” Moser said. “If a warehouse opens up down the street, people need to know about its cumulative impacts to know that they’re mad about it. And if they didn’t hear about (the project) first, they’re going to assume that the alderperson did know — even if they didn’t. … They’re going to assume you’re on the take.”

Ramirez said the ordinance would benefit her ward, and Black and Latino communities — “but really, all the city of Chicago.”

According to Moser, while some aldermen have said they will vote in favor of the ordinance when the time comes, they aren’t actively campaigning to pass it.

Some aldermen might be worried about the ordinance creating a longer, drawn-out zoning process that ignores businesses and creates more obstacles, Ramirez said.

“My argument to that is: You should put in the work before signing off on something,” she said. “Because, obviously, if there (are) legitimate concerns that we can make sure that we take care of, we should do that before allowing a permit.”

She said the new zoning rules will mean everybody wins at the end of the day.

“When you garner a lot of community support,” she said, “this at least allows us to get ahead of potential issues that may come up in the future, by addressing them earlier on.”

When the ordinance was finally brought before the City Council, it was almost a year after its planned introduction. And the yearslong process has not been without tension and disagreements. After the initial assessment in 2023, some South and West side residents said the report was flawed because a map identifying census tracts most burdened by pollution did not consider their proximity to Chicago’s 24 industrial corridors, where communities of color suffer from disproportionately prevalent chronic illnesses such as respiratory and cardiac disease.

More recently, some community activists blasted city officials for not making the ordinance available to the public beforehand — a move they called alienating after a mostly collaborative partnership with Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration. At the time, a spokesperson for the mayor said that city ordinances are not made public before their introduction.

Other groups, including N4EJ, have been more concerned with getting the ordinance passed first and working out the nitty-gritty of its implementation later.

“We’re hopeful to see this moving forward,” Moser said. “It’s been a long time coming.”