Julie Harris had never been tested for lung cancer. A low-dose CT scan, the only recommended screening for adults at risk of developing lung cancer, was not something she’d ever found time to do.

But when her primary care doctor recently suggested a new blood test to help look for signs of the disease, Harris was intrigued. She had her blood drawn the same day, in the same building as her doctor’s appointment.

“It was something that was accessible at the moment, so it was like, ‘Sure, let’s go ahead and do that and see how the results are,’” said Harris, 67, of Pekin. Harris, who is a longtime smoker, said if the results are positive, she’ll get a low-dose CT scan next to screen for the disease.

“Science just keeps moving forward,” she said.

Harris is among the first group of patients in Illinois to get the blood test as part of a pilot program at health system OSF HealthCare, which is offering the test at 18 locations. OSF leaders hope the blood test will improve early detection of lung cancer, which kills more people in the U.S. than any other single type of cancer.

OSF’s adoption of the blood test is part of a growing movement in medicine to use less invasive screenings to look for signs of cancer in patients, especially patients who may be reluctant to undergo more traditional, involved tests. A number of blood tests to help detect various types of cancer are now in development, according to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. Some health systems, such as OSF, are starting to offer the blood tests to patients, while others are waiting with cautious optimism for more long-term data on the tests.

“This is the future,” said Dr. Jared Meeker, a pulmonologist at OSF, said of the new blood test.

The blood test being used at OSF is not meant to replace a low-dose CT scan, which involves lying on a table that slides in and out of a type of X-ray machine.

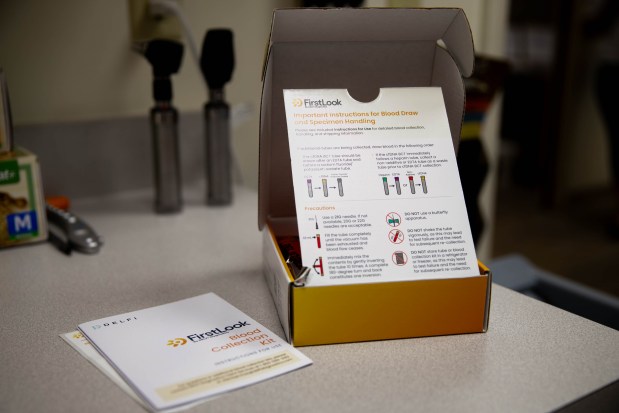

The FirstLook Lung blood test, developed by Delfi Diagnostics, based in California and Maryland, cannot diagnose lung cancer. But doctors hope that patients who might not want a CT scan – perhaps because it would require too much time, travel or effort – will consent to undergoing the blood test. If the blood test comes back positive, indicating a possibility of lung cancer, OSF leaders hope patients will then be more likely to agree to a low-dose CT scan.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that people at higher risk of developing lung cancer get low-dose CT scans annually. Higher-risk patients are those who are between the ages of 50 and 80 who have been moderate to heavy smokers, who are current smokers or who quit within the past 15 years. But only about 4.5% of those people actually got low-dose CT scans in 2022, according to an American Lung Association report.

“If everyone who was eligible for low-dose CT scanning was having it already, our test wouldn’t be helpful,” said Dr. Peter Bach, chief medical officer at Delfi. “The problem we have is they’re not, so what we’re trying to do is accelerate the conversations between them and their doctors about low-dose CT and inform them.”

The blood test works by looking for patterns of DNA fragments in the blood that could indicate lung cancer. If a person has lung cancer that would be detectable on a low-dose CT scan, there’s an 80% chance the blood test will come back positive, while if the blood test is negative, there’s a 99.8% chance the person does not have lung cancer, Bach said.

Delfi is seeking approval of its test from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which in recent weeks announced it plans to more tightly regulate laboratory developed tests. Until now, it’s primarily been the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services regulating laboratory testing. Delfi says the blood test has breakthrough designation from the FDA, which is a designation meant to help speed up the development, review and assessment of certain devices and products.

The blood test is not covered by health insurance, and Delfi declined to give a price. OSF leaders say they are still working out the pricing but are aiming to make the test as accessible as possible to patients. Neither OSF nor Delfi would say whether patients now undergoing the test at OSF are being charged. Low-dose CT scans are covered by health insurance.

Blood tests made by other companies to help detect cancers have list prices of about $900 to $950.

OSF doctors hope the blood test will lead to earlier detection for patients with lung cancer. The five-year survival rate for people with very small tumors that haven’t spread to the lymph nodes is 90%, but the five-year survival rate for people with lung cancer that has spread to other organs is only 7%, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

“No one wants to diagnose Stage 3 and Stage 4 lung cancer,” Meeker said. “It’s devastating.”

Patients might not always fully understand the implications of late diagnosis, said Dr. Tim Vega, chief population health officer at OSF.

“People think, ‘I’m smoking, if I get it, I’ll just check out very quickly,’” Vega said. “They don’t realize it could be years of difficulty for them and their families.”

At OSF, about 33% of eligible patients already receive low-dose CT scans — far better than national numbers — but still not as high as doctors would like, Vega said.

OSF leaders are looking toward the success of Cologuard as a model of how the new blood test might help patients. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Cologuard about 10 years ago as an at-home screening test for colon cancer. Patients mail a stool sample to a lab, which then analyzes it — a much quicker and less invasive task for patients than undergoing a colonoscopy.

As with the Delfi blood test, a positive result from Cologuard is not a cancer diagnosis, but means a person may have it and needs further testing. OSF started offering Cologuard to patients a few years ago and found that when patients get positive test results, they almost always agree to have a colonoscopy next, Vega said.

OSF isn’t the only health provider with high hopes for the blood test.

The White House recently noted, in an announcement about President Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot, that Delfi is working with the Indigenous PACT Foundation to improve lung cancer screening among American Indian tribes in the Pacific Northwest. Delfi is also working with City of Hope on a clinical study, funded by the American Cancer Society, to improve lung cancer screening in underserved Los Angeles County communities.

Doctors are keeping an eye on other types of blood tests as well, watching how they perform. Companies Grail and Guardant Health also offer blood tests to help detect various types of cancer.

University of Illinois Cancer Center is now involved in a clinical trial to help study Grail’s blood test, which screens for a cancer signal shared by multiple cancers.

“I still think that we have a long way to figure out how these types of tests fit into the broader context of cancer prevention and screening, but it’s very exciting,” said Dr. Ameen Salahudeen, an assistant professor of medicine at University of Illinois at Chicago, a member of the UI Cancer Center and an investigator in the trial, which is sponsored by Grail. “I never want to see someone with advanced cancer that could have been caught sooner, so personally, I believe that tests like these will have a role in the future.”

Dr. Rajat Thawani, an assistant professor of medicine at University of Chicago Medicine and thoracic oncologist, said such blood tests are promising, but before they’re adopted widely, more long-term data is likely needed about whether the tests can help lead to better quality and length of life for patients.

“There’s a lot of excitement in the utility of how it’s going to play out in the future, but I think right now we have to make sure it actually leads to a meaningful change in the longevity of patients,” Thawani said.

If the Delfi blood test makes a difference at OSF, leaders hope to offer it throughout the health system within a year, said Ryan Luginbuhl, OSF service line vice president for oncology services. OSF HealthCare has nearly 160 locations, including 16 hospitals, in Illinois and Michigan. Most of its locations are in central and northern Illinois, and the system includes OSF Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Evergreen Park as well as primary care, practices and urgent care centers in the Chicago area.

“We will do everything we can when we hope this proves to be effective … to get this to as many patients as possible,” Luginbuhl said.