In civics class, we’re taught the two-party system fits our nation perfectly. Yet third-party candidates and others have regularly been part of the quadrennial election. Third parties and splinter groups court voters who feel their issues have been ignored by Republicans and Democrats. Abraham Lincoln faced three opponents in 1860, and the U.S. seemed headed toward the European model of multiple parties and shifting coalitions.

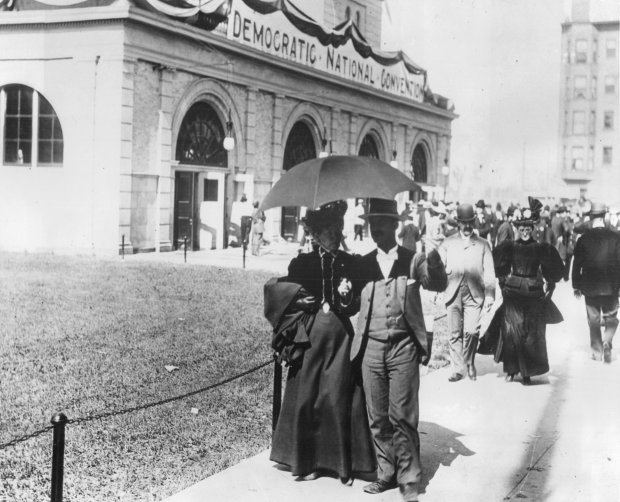

But on July 9, 1896, William Jennings Bryan endowed the two-party system with some life insurance. Stepping up to the podium of the Chicago Coliseum at 63rd Street and Stony Island Avenue, he demonstrated that reformers could profit from working within the system rather than fighting it.

Stretching his arms wide, he mimed Jesus’ crucifixion.

“You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns!” he thundered. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!”

Bryan played third-party politics to his advantage. A Democrat, he drew close to the Populist Party, a late 19th century reaction to big business’ domination of the two major parties.

“On all salient points Mr. Bryan is virtually a populist,” the Tribune wrote in 1894. “It was claimed during the Senate fight last fall that he joined the ranks of that party.”

Two years later, Bryan, a Democrat, and the upstart Populist Party both championed the same remedy for the debt load Americans incurred during three years of hard times: making silver, instead of only gold, an underpinning of the dollar. Western farmers pushed for the policy change because it would make it easier to get out of debt.

Eastern bankers and industrialists were opposed because their net worth would take a hit. Some blue-collar workers agreed. Increasing the money supply would inflate the cost of their groceries.

At the 1896 convention, Democrats on each side of the issue tried to unseat the other’s delegates. A leader or opponent of the “free silver movement” gave the principal address at each session.

Representing the pro-silver faction, Bryan spoke for the hard-pressed and unheard:

“We have petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated, and our entreaties have been disregarded; we have begged, and they have mocked, our calamity came. We beg no longer; we entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them.” William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic Party presidential candidate, stands on stage next to an American flag, circa Oct. 3, 1896. (Library of Congress)[/caption]

The Tribune reported that after hearing Bryan’s oration: “Three-fourths of the delegates stood upon their chairs and waved handkerchiefs, umbrellas and hats.”

But the Democratic Party’s old guard deserted en masse.

“On the very first roll call the zealous silver men were again reminded that the Democratic Party was divided,” the New York Times reported. Delegates favoring the gold standard refused to vote, including the entire delegations from New York and New Jersey.

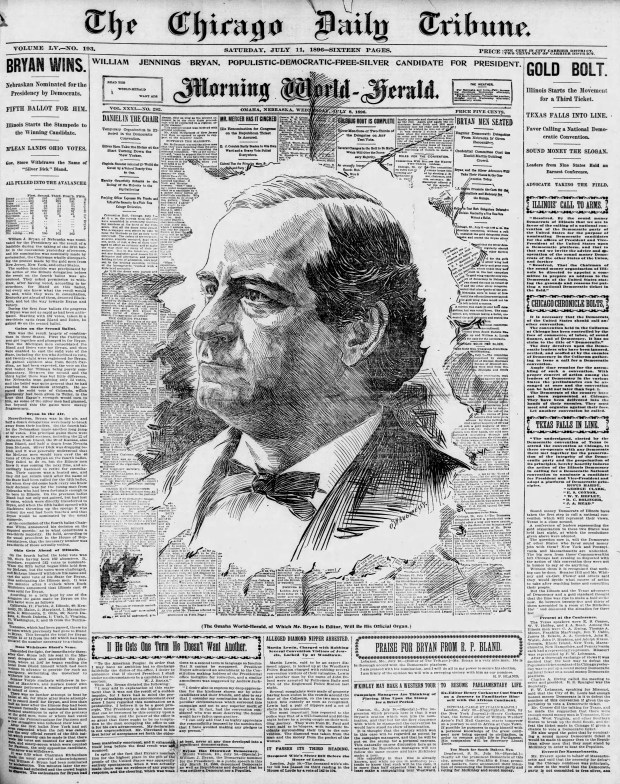

Their forfeiture gave Bryan the Democrats’ presidential nomination on the fifth ballot. The Tribune congratulated him with the headline: “Bryan Made a Lion.”

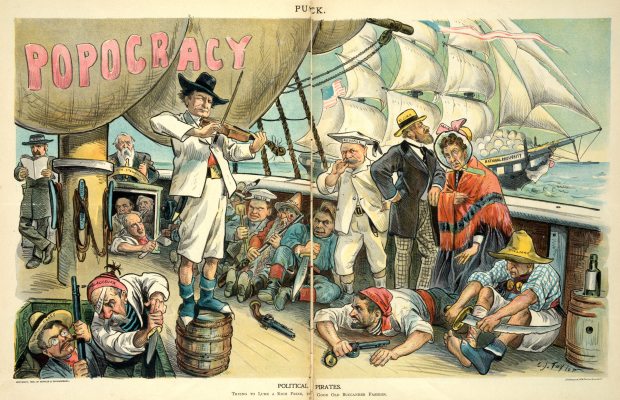

The Peoples, or Populist, Party named Bryant their candidate as well. The Democratic Party was split. Wisconsin’s hard-money Democrats endorsed Bryan with a counterattack on the Populists who, the Tribune wrote, “hailed his nomination with delight as a harbinger of success to their communistic theories.”

The staunchly Republican Tribune made clear its feelings about Bryan.

“Careful and impartial investigation of the personal, political and professional record of William Jennings Bryan will convince anyone that he is not fit to become President of the United States,” the paper wrote a couple of weeks after the convention.

Old friends and new enemies dubbed him “Popocrat,” since he was straddling two parties. He was also known as the “Boy Orator of the Platte,” an honorific reflecting his precocious mastery of public speaking. Born in Illinois, Bryan moved to Nebraska, a state bisected by the Platte River, after law school.

He knew the agony of blue-collar constituents who had lost a farm to the vagaries of commodity prices or a parched growing season. As a candidate, he was preaching a solution to debtors’ plight that was rejected by the incumbent president, Grover Cleveland, a fellow Democrat. Many workaday voters didn’t buy the argument that tampering with the monetary system would yield a better tomorrow.

Bryan’s support by Democratic officials was shaky from the day he left for New York, where a “notification ceremony” for his nomination was planned in Madison Square Garden. “Not over twenty persons, including the hotel attaches, gave him a cheer or a ‘God speed’ at the hotel, but no one went to the Union depot,” to see him off, the Tribune reported on Aug. 10, 1896.

In New York, a screaming and stomping audience filled the Manhattan arena. But New York’s mayor was a no-show. Wall Street tycoons and showbiz luminaries dodged photo shoots. The highest ranking official willing to introduce Bryan was an obscure former state treasurer.

The Tribune gloated over Bryan and U.S. Secretary of State John Carlisle simultaneously visiting New York. Yet Carlisle, a Democrat, didn’t huddle with Bryan, a Democrat running for president.

Carlisle left New York, the Tribune noted: “Without apparent consciousness that the boy orator who has undertaken to whip the money changers from the temple of Popocracy was within a thousand miles of the metropolis.”

Bryan’s campaign was doomed. Newspapers distributed the idea that he was a subversive whose radical proposals would kill what was left of America’s economy. That subjected Bryan to a witch hunt similar to the redbaiting after World War I and World War II. Major newspapers that leaned Democratic said they couldn’t support Bryan because of the platform he was running on.

After Bryan’s New York appearance, his advisers met with him.

“All day long Senator Jones, Governor Stone, and others talked with Bryan over the results of the Madison Square celebration and attempted to convince him that he should not continue his eastern trip,” the Tribune reported.

He rejected their advice. He wasn’t deterred by the defection of Democratic allies.

“The humblest citizen of the land when clad in the armor of a righteous cause is stronger than all the hosts of error that they can bring,” Bryan said in his Chicago convention speech.

By Election Day, he’d made 250 speeches, creating a prototype for whistle-stop campaigns. The turnout was high, reportedly 90% in some precincts.

William McKinley, the Republican candidate, won both the popular vote and the Electoral College, although he carried only one more state than did Bryan, who got 47% of the popular vote.

The Populist Party ticket, made up of Bryan and a running mate, received a thin and meaningless slice of the vote, and with that essentially disappeared. The Democrats went on to nominate Bryan as their candidate twice more.

He lost both times.

Sign up to receive the Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter at chicagotribune.com/newsletters for more photos and stories from the Tribune’s archives.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com.