Bill Melton, the first Chicago White Sox player to hit 30 home runs in a season and the first to lead the American League in homers, died Thursday at age 79.

The Sox said Melton, who played eight of his 10 major-league seasons for them, died in Phoenix after a brief illness.

Melton’s playing career ended early, at age 31, because of recurring back problems. The always blunt and outspoken Melton, who often battled with the Chicago media during his playing days, later became a Sox TV analyst.

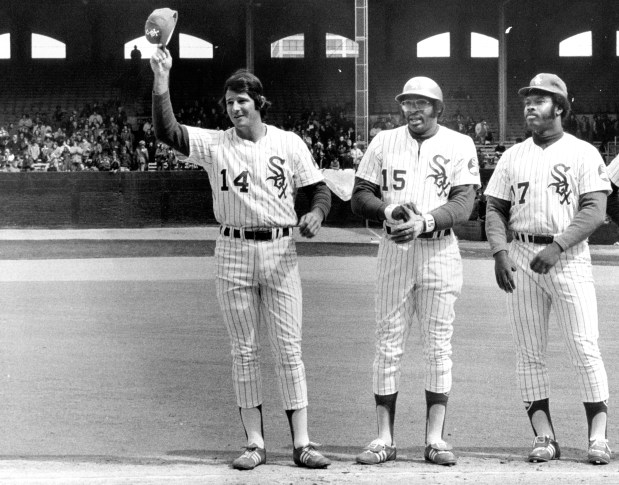

“Bill Melton enjoyed two tremendous careers with the White Sox,” Chairman Jerry Reinsdorf said in a statement. “His first came as a celebrated home run king for White Sox teams in the early 1970s, where ‘Beltin’ Bill’ brought power to a franchise that played its home games in a pitcher-friendly ballpark. Photos of Bill wearing his home run crown and others of him posing with ballpark organist Nancy Faust still generate smiles to this day.

“Bill’s second career came as a well-liked and respected pre- and postgame television analyst, where on a nightly basis Sox fans saw his passion for the team, win or lose. Bill was a friend to many at the White Sox and around baseball, and his booming voice will be missed. Our sympathies go out to his wife, Tess, and all of their family and friends.”

Melton was born on July 7, 1945, in Gulfport, Miss. He attended Citrus College in Glendora, Calif., which is where Sox scouts found him and signed him to a professional contract. He made his major-league debut with the Sox on May 4, 1968, at age 22.

A converted outfielder, he was less than graceful at third base, his primary position with the Sox, but he felt his bat more than compensated for his glove work.

“In the old days you were just a clunker,” Melton told the Tribune in 2016. “All you had to do was just stand out there, cement yourself in the ground, and as long as you hit home runs and RBIs, they didn’t care if you caught it or not. Now the game is a lot more about defense. There’s so much athleticism. You see how valuable that is because there are so few of them.”

Melton’s value wasn’t universally appreciated during his time with the Sox. His tenure with the team was marked by hurt feelings and physical pain.

“When we lost 106 games (in 1970), it was humiliating,” Melton recalled. “They said we were the worst team in baseball and I was the worst third baseman.”

Melton hit 33 homers in 1970, the first Sox player to reach the 30-homer mark in a season. He followed up with 33 more in 1971, becoming the first Sox player to lead the league. He also made his lone All-Star team that year.

Melton’s chase for the AL home run title was loaded with drama and came down to the final game of the ’71 season.

“I was in a battle with Reggie Jackson and Norm Cash. I had 30 and they had 32,” Melton recalled. “I hit two home runs the last night game of the season, so I tied them. But I had one game remaining on a Wednesday afternoon (against the Milwaukee Brewers at Comiskey Park). I’ll never forget it. It was Sept. 30, and it was like 95 degrees.”

To give Melton as many at-bats as possible, Sox manager Chuck Tanner put him in the leadoff spot.

“The game started at noon and I hit a home run,” Melton said. “Being the first White Sox player ever to lead the league in home runs and the first White Sox player ever to hit 30 homers — it sounds so minute now. But at that time it was a pretty good feat.“

That was about as good as it would get for Melton. A back injury limited him to 57 games in 1972 and nearly ended his career.

“The pain … the ache inside, was something else,” Melton recalled. “First, those three months on my back. I couldn’t sit up for five minutes to eat. Then back on the floor.”

Melton underwent a rigorous rehab program and bounced back with a 20-homer season in 1973.

“I had my doubts,” he said. “I was scared to death, to be honest, because I had lost the feeling in my leg.”

Melton was batting .299 with 13 homers and a team-high 58 RBIs at the All-Star break that year and felt he should have been voted onto the All-Star team or at least selected as a reserve. When neither came to pass — he finished a distant second in fan voting to the Baltimore Orioles’ Brooks Robinson — he felt snubbed.

“I don’t think the Chicago press backed me up enough,” he said.

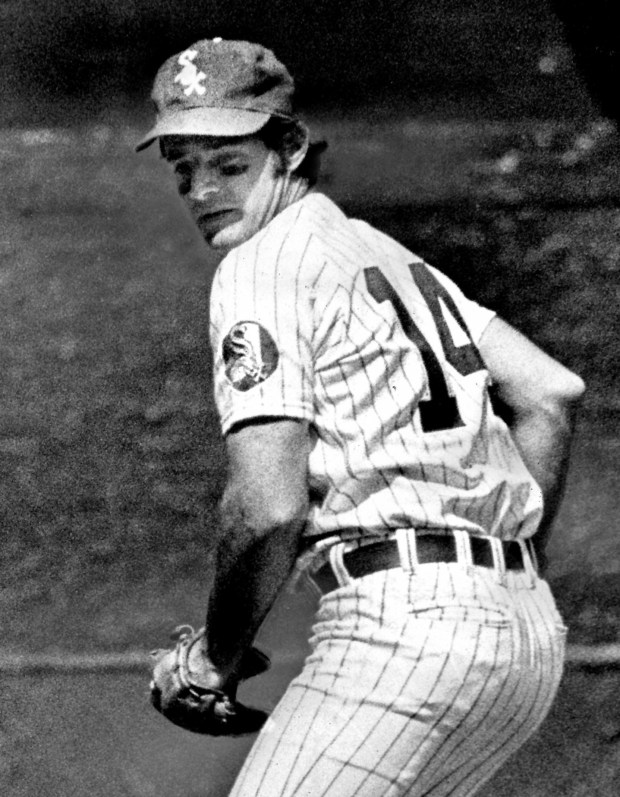

White Sox third baseman Bill Melton during a game against the Yankees on Sept. 11, 1968. (Ed Wagner Jr./Chicago Tribune)

After the Sox acquired veteran third baseman Ron Santo from the Chicago Cubs before the 1974 season, Tanner said he planned to keep Melton at third and use Santo as a designated hitter.

Melton was asked during spring training if he would accept those roles being reversed, considering Santo was a nine-time All-Star, albeit at the end of his career, and a five-time Gold Glove winner.

“That would upset me,” Melton responded with typical honesty. “But later, if I’m not doing the job … that would be something different.”

The Santo deal irked Melton, as did the frequent criticism he received from play-by-play man Harry Caray. Melton was especially irritated by a quote from Caray that appeared in a column by the Tribune’s Gary Deeb: “It’s pretty tough not to be critical, especially when (Melton) loafs on the job.”

“There are 25 guys on this team who are sick and tired of (Caray),” Melton said in 1975. “We keep our criticisms of him in the clubhouse, though. We don’t blast him like he blasts us. But I’ve finally had it and I can’t keep it in any longer.”

The Melton-Caray feud reached new heights after the broadcaster questioned Melton’s baserunning during a 1975 game in Milwaukee.

“He harped on it and harped on it, and all I was doing was playing heads-up baseball,” Melton said. “I’m tired of going everyplace and hearing that Caray is jumping all over me on every broadcast. Then he comes over to me (not long after the Milwaukee game) real sarcastic and says, ‘What’s wrong, is little sweetheart Billy upset over something?’ I could have popped him one.”

Taking their cue from the popular Caray, fans started to turn on the former home run champ.

“The people of Chicago are down on me now, but I just want them to know that I’m trying,” Melton said. “I’m busting my butt. I’m not trying to strike out, I’m not trying to pop up, I’m not trying to be traded. But if I was, the reason I’d be happiest to leave is because of that man (Caray) upstairs.”

Melton’s former teammate Ed Herrmann, who had moved on to the New York Yankees by 1975, offered his perspective of the feud: “Something’s got to happen soon. It’s been going on too long. Either Melton, Caray or Chuck Tanner will go. I’m just glad I don’t have to hear that stuff anymore.”

As the ’75 season wound down, Hermann’s words became prophetic.

“Bill has admitted that it’s become hard to play here,” Sox general manager Roland Hemond said that September, “that some of the fun has gone out of it. And I’m sure that his name will be brought up (in trade discussions) during the winter. Both he and Kenny (Henderson) have undergone unwarranted criticism all season. When it starts from opening day, you wonder why.”

The Sox decided to make a clean sweep. On Dec. 11, 1975, they traded Melton to the California Angels. Henderson was traded to the Atlanta Braves. Tanner reportedly was offered a demotion but chose to take the managing job with the Oakland Athletics.

And Sox owner John Allyn fired Caray. But after Allyn’s deal to sell the team to Bill Veeck was approved, Caray was reinstated.

Melton, who lived in California during the offseason, expressed relief at his trade to the West Coast.

“I’ve been waiting for this for two years,” he said when reporters reached him at his home in Mission Viejo. “I had to get out of Chicago.”

Melton eventually returned — ironically as an outspoken and occasionally critical broadcaster and analyst for Sox games.

“(Caray’s) criticism was more personal,” Melton said in 2005. “If I made it a personal issue, I wouldn’t be in the business. The media exposure now is huge, and anything can be taken out of context.”

Joe Knowles is a former Chicago Tribune sports editor.