Did you know there’s a very specific reason we have a fall book season?

It’s not the only reason, but it’s the reason that set this cultural cycle in motion. Long story short: As New York and Philadelphia became hubs for publishing in the United States, there was a need to sell more books to a burgeoning Midwest — Chicago, St. Louis, Cleveland. The problem was the Susquehanna River and Erie Canal, the industry’s primary shipping routes. They were frozen roughly from Christmas to Easter. So starting in the mid-19th century or so, publishers would wait until the big thaw, particularly autumn, to release their big titles, ensuring new department stores like Chicago’s Marshall Fields and Detroit’s Hudson’s had plenty of books for holiday gifts.

“Geography is destiny,” Napoleon supposedly once said.

If the new fall book season looks overwhelming — Al Pacino’s memoirs, and a new Haruki Murakami epic? — if you’re about to triple your To-Be-Read pile, I guess blame the Erie Canal. Also blame a great time for biographies. An explosion of diverse voices. A horror renaissance. And no shortage of legendary authors waiting to break the ice.

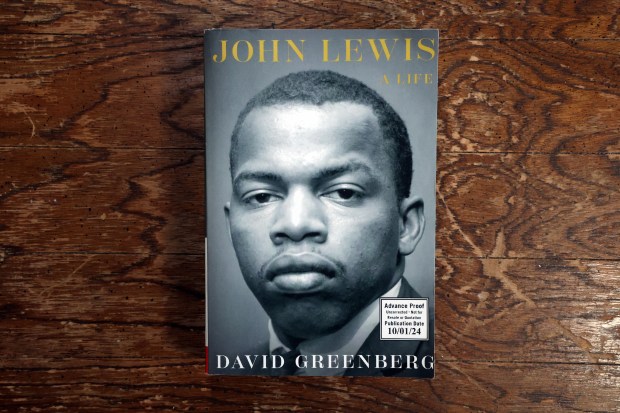

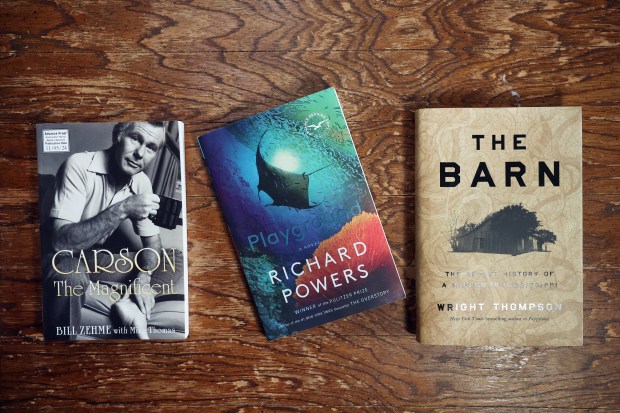

Bio-picks

Before he died last year, Bill Zehme, Chicago-based celebrity whisperer, was deep into a definitive biography of Johnny Carson, who gave Zehme his first interview after retiring from “The Tonight Show.” What Zehme finished (with Chicago Sun-Times writer Mike Thomas) makes up the core of “Carson the Magnificent” (Nov. 5), a lively account heavy on the talk-show legend’s rise to fame. Did you know Congressman John Lewis once went to New York Comic Con dressed/cosplaying in the outfit he wore to the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma? That and more paint the definitive, admiring images of “John Lewis: A Life” (Oct. 8), David Greenberg’s thorough portrait of the Civil Rights icon (who did interviews with Greenberg before his 2020 death). “Lovely One,” the new memoir by Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, shares some of the formality of that Lewis book — it gets personal, but not that personal. You don’t get much insight into the Supreme Court, but you do get a tender, old-fashioned stoicism from the first Black woman to serve on the nation’s highest court.

Short, not shallow

The problem with fall is you’re ready to learn but the abundance of the season leaves little time for deep dives. Might I suggest the new Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose “Between the World and Me” was a generation-defining study of race? His latest, “The Message” (Oct. 1), just as slender and poignant, is centered on travel narratives (Palestine, South Carolina, Senegal) about the legacy of myth, censorship and country. “Bone of the Bone: Essays on America by a Daughter of the Working Class,” by Sarah Smarsh (2019 winner of the Tribune’s Heartland Prize), is a long-promised journalism collection about Americans just getting by that avoids straw men and glibness, with thoughts on dentistry, working at Hooters and arguing with Trump voters. “The Position of Spoons: And Other Intimacies” (Oct. 1), by ultra-prolific Deborah Levy, plays like a lunch with an especially sharp, scattered pal, with brief (often one or two pages total) thoughts on celebrity death, Collette, female friendships, lemons…

The stuff of the Midwest

“The Registry of Forgotten Objects: Stories,” by Chicago’s Miles Harvey, chair of the English department at DePaul University, has an addicting theme: A debut collection in which characters are about to disappear but the tactile things of their lives — Eudora Welty books, old buoys, strange tunnels — go on. If you’ve ever felt sort of haunted by something you own, you’ll relate. “A Reason to See You Again” (Sept. 24) by Buffalo Grove native (and #1000WordsofSummer project founder) Jami Attenberg, is not about objects, but by leanly tracing the collapse of a Midwest family from 1971 to 2007 (in a third of the pages of a Jonathan Franzen), she can’t help but linger lovingly over artifacts — like ashtrays, indoor malls, magazines…

The New Masters

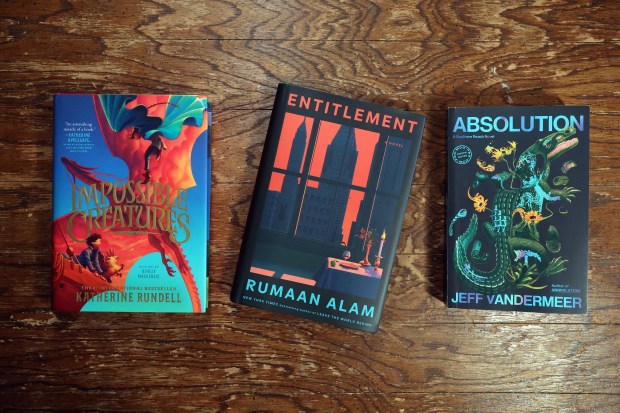

Booker Prize-winner Alan Hollinghurst (“The Line of Beauty”) returns to the territory once owned by Martin Amis with “Our Evenings” (Oct. 8), another devastating study of privilege, tracing the fortunes of a half-Burmese man from his scholarship days at a boarding school to his soaring future — setting off the reactionary spite of Brexit. Speaking of award-winners: Always-ambitious Evanston native Richard Powers returns to the environment for “Playground” (Sept. 24), another sprawling science epic that draws in entire worlds. Whereas “The Overstory” was set among trees, this is in the ocean, to tell the story of a set of people (including two Chicago students) on an atoll where floating cities are being tested. If Powers has remade the way novelists use the environment, Rumaan Alam revived the gilded moral parable. “Entitlement” (Sept. 17), like Alam’s bestselling “Leave the World Behind,” both cringes at crass unexamined wealth and longs for an easy frictionless life, telling the tale of a modest woman tasked with giving away a billionaire’s fortune. (“This was an illness,” she thinks late in the book, seeing new rooms only for how their size compares to smaller rooms.) For something less intense (but just as accomplished): “Death at the Sign of the Rook” is Kate Atkinson’s return to her Jackson Brodie mysteries, a very Agatha Christie-inspired tribute to big British mansions, lots of guests and one murder.

The best writer you’re not reading (yet)

Katherine Rundell is due, but it’s understandable why the name is not familiar. She wrote a devilishly fun biography of poet John Donne (“Super-Infinite”) but is best known (in England) for children’s books. This season, she delivers a bit of everything: “Vanishing Treasures: A Bestiary of Extraordinary Endangered Creatures” (Nov. 12) is composed of nearly two dozen hilarious strange, totally true essays about the natural world that summon real wonder. (“Hey,” I yelled to my wife while reading, “hermit crabs probably ate Amelia Earhart!”) The breakthrough, however, looks like “Impossible Creatures,” already a smash in Europe, a YA epic with the wisdom of Tolkien and the accessibility of Rowling. It’s set inside an island chain, hidden from mankind, where every mythological monster lives.

Streets of dreams

“In this real world, you and I live not so far from each other,” writes Haruki Murakami in his first novel in six years, “The City and Its Uncertain Walls” (Nov. 19). That’s not a bad way of describing his latest (or any of his novels). It tells the story of libraries and Dream Readers who review our dreams — and if that sounds vague, you’ve never read this eventual Nobel Prize winner. Comparably, “The Great When” (Oct. 1) — about a parallel London that must never be revealed — is straightforward, yet as effectively moody as you might expect from author Alan Moore, best known for his benchmark comics “Watchmen” and “V For Vendetta.”

Speaking of megalopolises

The one must-read Chicago history of the season: “The Daley Show: Inside the Transformative Reign of Chicago’s Richard M. Daley” reads much more critically than you might expect considering the author is Chicago political staple Forrest Claypool (a Daley chief of staff). But this is a readable, even compelling, account of how an administration flopped (the parking meter fiasco), bullied and scored. Still, it has nothing on “Paradise Bronx: The Life and Times of New York’s Greatest Borough,” one of the year’s best, a delightful amble (literally at times) by the great Ian Frazier, who mixes traditional history, shoe-leather reporting and the random detail that explains a lifetime of hustling, art-making and gentrification.

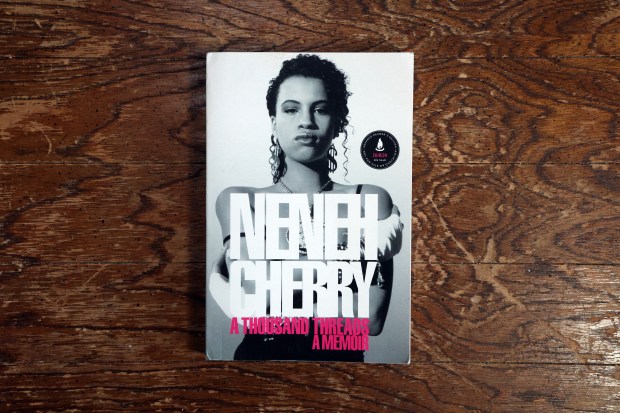

Footnotes no more

“A Thousand Threads” (Oct. 8) is not really the memoir of Neneh Cherry — best known as the one-hit wonder behind the great 1989 single “Buffalo Stance” — but a snapshot of a music family (her step-father was jazz great Don Cherry), over decades, from Sweden to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. Likewise, “Welcome to Pawnee: Stories of Friendship, Waffles and Parks and Recreation” (Nov. 24) is only tangentially the autobiography of Chicago’s Jim O’Heir, best known as the Santa-like Jerry, human doormat of “Parks and Recreation.” It’s more of a warm reminisce of a beloved show, full of backstage lore and guest commentary.

Picture pages

“Einstein in Kafkaland: How Albert Fell Down the Rabbit Hole and Came Up With the Universe” is Evanston cartoonist Ken Krimstein’s playful follow-up to his Holocaust bestseller “When I Grow Up.” With a dip into dream logic, and lots of historical truth, Einstein and Kafka meet in Prague, on the cusp of world-changing ideas. It’s a light walk into the academic year, but far from a slight one. Charles Burns’ graphic novels have long lived in the liminal land between reality and dreams — with an added heap of body horror. Maybe no more so than his ethereal new “Final Cut” (Sept. 24), about a group of friends awkwardly tip-toeing around their unsaid feelings while shooting a no-budget remake of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.”

Our town, every town

There’s no shared connection between Elizabeth Strout’s “Tell Me Everything,” Louise Erdrich’s “The Mighty Red” (Oct. 24) and Richard Price’s “Lazarus Man” (Nov. 12), other than this: Each is a major statement by a major author, and each is less about its characters than how entire communities mesh. Price, always underrated, returns after a decade with the intertwining stories of the tenants, cops and neighbors affected by a building collapse; it’s a terrific read. Erdrich, who won the 2021 fiction Pulitzer for “The Night Watchman,” focuses on a set of people living on North Dakota’s Red River; Strout, winner of the 2009 fiction Pulitzer, returns to a small town in Maine. Nothing much happens in these novels, except everything happens.

Famous lives, fresh takes

“Survival is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde,” one of the year’s best, is the biography that Lorde — too often known by a line here, a quote there — needed. Wandering, unorthodox, Alexis Pauline Gumbs melds her prodigious mind to Lorde, illuminating how the activist/poet saw her own life as inspiration, long after her death in 1992. English biographer Craig Brown — “150 Glimpses of the Beatles,” “Ninety-Nine Glimpses of Princess Margaret” — never met a life he couldn’t have a blast with, splintering narrative, inserting cultural history, essay, jokes. “Q: A Voyage Around the Queen” (Oct. 1) takes on Queen Elizabeth II the way most people knew her, through jewels, lyrics, wedding lore, anecdotal encounters. Similarly, culture writer Rob Sheffield’s “Heartbreak is the National Anthem” (Nov. 24) is an impressionistic portrait of Taylor Swift, a slender one, not remotely definitive, but rather, more interesting — the first serious attempt to place Swift inside a music history.

Interior design

The first words you read on the inside flap of “The Repeat Room” (Sept. 24), Jesse Ball’s new novel, is “Franz Kafka” — Ball, a longtime instructor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, is indeed an accomplished chronicler of bureaucratic hell. But “The Repeat Room,” about a justice system in which a juror inhabits a defendant’s life, melds Ball’s experimental ambition into a sorta thriller in new ways. Like Ball, Garth Greenwell moonlights as a poet. “Small Rain,” his latest, tells the story of a poet whose sharp debilitating pains drag him through, yes, a Kafkaesque health system.

Return to form

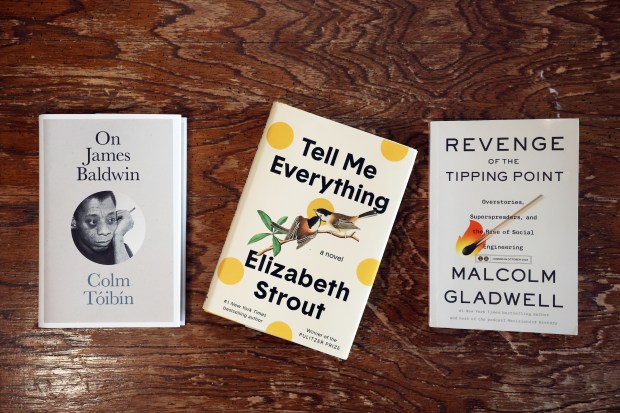

“A new set of theories, stories and arguments about the strange pathways that ideas and behavior follow through the world.” That’s how Malcolm Gladwell describes “Revenge of the Tipping Point” (Oct. 1), written to mark the 25th anniversary of his mega-seller “The Tipping Point,” but also, I suspect, to fine tune the overly-tidy conclusions that marked his illuminating premises. Subjects this time include “Will & Grace,” bank robberies and rugby teams. Like Gladwell, everyone assumed Jeff VanderMeer moved on from his greatest hit, the Southern Reach trilogy (best know by its Natalie Portman adaptation “Annihilation”). “Absolution” (Oct. 22) is a 400-plus page addendum, tying up (some) loose ends of a dreamy series that drew its power from iffy-answers about Florida’s quarantined Area X.

Fresh eyes

A single book can remap your world. Exhibit A: Sarah Lewis’ “The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America” (Sept. 17), no less than a revelatory history of how, from the Civil War to the early 20th century, Americans crafted images of race, filtering out contradictions to arrive at something simplified. Ben Macintyre, who perfected the nonfiction-espionage genre, returns with “The Siege,” retelling the forgotten six days in 1980 when armed men took over the Iranian embassy in London; it reads like a missing piece to the Middle East puzzle. “Fierce Desires: A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America,” by scholar Rebecca Davis, is an absorbing sorta-secret road trip through the ways in which contemporary fears about identity and sexualized culture have 400 years of antecedents, profiling the subcultures, pioneers and anti-sex crusaders who still echo through generations. In the 70 years since Chicago’s Emmett Till was tortured and murdered in Mississippi, you’d assume no stone’s been left unturned. But Wright Thompson’s remarkable new account, “The Barn” (Sept. 24) — the title being a nod to his family farm, 20 miles from the killing — considers the ugly history of the region’s residents, and the inevitability of the crime.

Your brain on parenthood

If the literature of understanding kids is robust (and often eye-rolling), the literature of just trying to exist and stay sane as a parent feels kind of nonexistent. That’s why I devoured “Lifeform” (Oct. 22), by actor/comic Jenny Slate, as if it were a strange and very funny email from a good friend. Maybe you can relate: After becoming a mother during the pandemic, she wrote an ode to her dishwasher, imaginary letters to doctors (“Do I have a crack running down from my dome to my flippers?”) an essay on eating yogurt. It’s a lovely set of essays on an impossible-to-describe mindset. “Childish Literature” (Oct. 8), by Alejandro Zambra (“Chilean Poet”), though more grounded, considers fatherhood, beginning with the truism that some fathers “lose their ability” to exist outside of their offspring and become self-appointed “spiritual leaders” of children. If that sounds serious, his subjects are decidedly earthy, childhood memory, screen time, losing touch with the obsessions of your previous life…

Lit lives

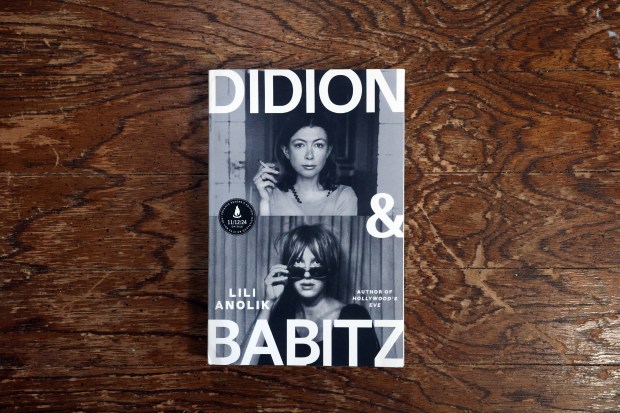

It’s not hard to find thoughtful words on James Baldwin, but if you’re going to read one appreciation — this is Baldwin’s centenary — “On James Baldwin,” a slender essay collection by Irish writer Colm Tóibín, is a good start, a smart novelist’s consideration of how an even better writer’s work touched his life and work. For a much messier literary relationship: “Didion & Babitz” (Nov. 12) is Eve Babitz biographer Lili Anolik’s dueling account of the frenemy-ship between Joan Didion and Eve Babitz, ‘70s-bred breakthrough writers whose daring works are experiencing their umpteenth revival. At the other end of the pen: “The World She Edited: Katharine S. White at the New Yorker” is the credit that White — who did as much in the magazine’s early years to define its intelligence as her famous husband (E.B. White) — has long deserved. The revelation of this finely-researched biography is how transformative she was toward a generation of women authors, becoming a center of gravity for all 20th century fiction.

Bloody good

Mariana Enríquez’s 2023 epic “Our Share of the Night” was a word-of-mouth hit, but if word never got to you, try “A Sunny Place for Shady People” (Sept. 17), the Argentine writer’s new collection of Latin American horror stories, including a town run by ghosts (“The neighborhood has changed since I was little”), melting faces and reminders of dictatorships and the disappeared. Other ghosts of a sort: “Good Night, Sleep Tight” is the latest excellent batch of weird stories by Brian Evenson, whose underrated, apocalyptic night terrors tread the fertile ground between George Saunders and Gabriel García Márquez. This new collection is less excited about AI than your boss may be. For a single unsettling tale: “Pay the Piper” is the latest beyond-the-grave collaboration between Evanston’s Daniel Kraus and late filmmaker George A. Romero. Kraus, who previously completed Romero’s unfinished “Living Dead” novel, found “Pay the Piper” in Romero’s papers. But no zombies this time — swamp monsters.

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com

- Movies for fall 2024: Our film picks and questions about everything from “Wicked I” to “Joker II.” (Michael Phillips)

- TV for fall 2024: Our top 20 shows coming down the pike, including a hospital comedy from the creator of “Superstore.” (Nina Metz)

- Theater for fall 2024: Our top 10 upcoming titles from “Potter” to “Pericles.” (Chris Jones)

- Dance for fall 2024: U.S. premieres at Joffrey and the Harris, plus Hubbard Street does Fosse. (Lauren Warnecke)

- Live music for fall 2024: Iron Maiden, Usher and a return for Billie Eilish. (Bob Gendron)

- Classical and jazz for 2024: The hidden, the one-offs, the thoroughly unmissable. (Hannah Edgar)

- Museums for fall 2024: 10 can’t-miss exhibitions to check out this season. (Hannah Edgar)

- Art for fall 2024: Top 10 exhibitions at AIC, DePaul and the Cultural Center. (Lori Waxman)