This wasn’t the speech Jose Wilson had hoped to give after making a run for Democratic committeeperson in Chicago’s 1st Ward.

Two months before votes were cast in the March primary, the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners booted Wilson from the ballot. Though Wilson had turned in nearly 1,700 signatures on his nominating petitions — knocking on doors for weeks last fall and winter — one of his rivals torpedoed Wilson’s candidacy by successfully challenging enough of those signatures to keep him off the ballot.

And so, at a sparsely attended January hearing inside a sterile government conference room, Wilson rose to deliver his last speech of the race, directing his frustration at a cutthroat Illinois balloting process a Tribune investigation found is overly complicated, limits voters’ choices and contributes to corruption that plagues government throughout the state.

“I don’t think it’s fair,” Wilson told election board members. “I don’t think it’s clear. I don’t think it’s transparent.”

It is, however, a system firmly entrenched in Illinois, one that makes it harder for people to qualify for the ballot than in many states and easier to get kicked off.

The system grants incumbents an inherent advantage over neophytes who are new to the arcane balloting rules, some of which were written by the same veteran politicians who now reap the benefits. Using a cadre of well-versed attorneys, insiders thwart challengers before the first votes are cast, often on questionable grounds.

It is, in essence, a way for the state’s political power brokers to control the options voters have to choose from even if they can’t control people’s actual votes.

As the Tribune continues to examine Illinois’ notorious political history in the series “Culture of Corruption,” the state’s convoluted ballot process provides a vivid demonstration of how generations of political leaders have leveraged election laws to stay in power even as corruption charges ensnared many of their chosen favorites.

Some of those leaders are facing corruption allegations today, including longtime House Speaker Michael Madigan, whose bribery and extortion trial got underway last week. He’s pleaded not guilty to a 23-count indictment, including an allegation that he helped coerce utility giant AT&T into hiring a former lawmaker — someone who received help from Madigan’s allies in knocking challengers off the ballot.

Defenders of the system argue it ensures only serious candidates appear on the ballot and that Illinois elections don’t devolve into chaos. In California, for example, more lenient rules have at times allowed dozens of people to run for governor or senator.

The counterargument is that the Illinois ballot process forces candidates to navigate a different kind of chaos, in a game played at all levels by all types. Barack Obama used it to win a seat in the General Assembly, launching his political career.

Obama chose that path; others get dragged in. Last winter, then-82-year-old Danny Davis, the veteran U.S. congressman, was summoned to a city elections hearing to refute a claim his campaign had forged Davis’ signature on election paperwork — an allegation for which Davis’ rival offered no evidence. The challenge was later dropped, and Davis won the primary against several opponents.

“It’s all a tactic,” a resigned and bemused Davis explained to a reporter. “Just delay, hold you back, keep you busy, spend your resources, and there’s no other purpose except for that.”

Disputing a candidate’s own signature was unusual. More commonly, candidates challenge voters’ signatures on nominating petitions, triggering lengthy hearings in which elections officials not only check yes-or-no questions such as whether a signer is registered to vote, but also make hundreds of judgment calls on whether a signature matches the one on file with the elections board.

The Tribune found multiple instances in which officials rejected the signatures of voters who not only insisted to a reporter that their signatures were legitimate but also swore to it in notarized affidavits.

Most candidates survive the challenges but are so drained of cash and energy that long-shot bids face even longer odds. And some, like Wilson, don’t even make it on the ballot.

Among those expressing frustration is state Rep. Kelly Cassidy, a Chicago Democrat who said she accepted assistance from Madigan’s legal team in one race before deciding to reject further help. Cassidy has since pushed legislation to reduce the required number of signatures and to create an electronic signature process where voter information could be checked when a signature is gathered.

“The game is rigged against folks without means,” she said, “and I think we’re better than that.”

Rules of the game

Here’s how the ballot challenge process works: A political candidate — or, more often, an ally — gets copies of all the election petitions filed by a rival, then scours the paperwork for any perceived deviations from a complicated set of rules in Illinois law about how signatures must be gathered and turned in.

Given the complexities, it’s rare for even the most diligent candidate to turn in a perfect set of paperwork. Maybe a page lacked the right signature of a campaign worker. Or there was a typo in the candidate’s name. Or the office wasn’t described precisely the right way. It’s a nitpicker’s delight.

But most time is spent going through a candidate’s petition line by line to see who signed in support of having the candidate’s name on the ballot, then checking those signatures against voter information kept by the county.

Rivals check to see if the person who signed is a registered voter or if they are registered at the address listed on the petition. They also check to see if the signers live outside the boundaries of the district the candidate wants to represent. Those are the most common reasons a signature is rejected.

Often challengers level a different allegation, one that is easy to make and can take much longer to refute: that a signature on the petition isn’t genuine.

To pursue any of these allegations, candidates typically find a proxy willing to put their name on the challenge and hire a lawyer from among a dozen or so who specialize in this kind of work to formally pursue the case. Often the challengers suggest a wide range of potential misdeeds, like throwing spaghetti against the wall to see what may stick.

Elections agencies are duty-bound to hear the challenges. And for each election cycle, taxpayers must cover the costs of not only agency employees but also contractors hired to serve as hearing officers, court reporters and handwriting experts. For the March primary, the city, county and state elections boards collectively paid $230,000 in outside fees.

Challenges don’t occur only in big races. This summer, nearly one-third of would-be Chicago school board candidates were chopped from the ballot after a challenge process involving high-profile political operatives and lobbyists. And a 2013 Tribune investigation documented how some suburban leaders stacked local electoral boards with allies who knocked rivals off the ballot over trivial and debatable paperwork mistakes.

Incumbents who fail to master the system risk getting booted by a savvy newcomer. That’s something state Sen. Alice Palmer learned in 1996, when Obama, then a little-known civil rights lawyer, filed challenges that pushed Palmer and three other competitors off the Democratic primary ballot as she ran for reelection.

Obama’s efforts gave primary voters just one choice for a job that took him to the General Assembly, followed by the U.S. Senate and the White House.

When asked about the challenges during his first White House run, Obama fell back to a common defense: Rules are rules, and if you can’t follow them, you don’t deserve the job.

“My conclusion was that if you couldn’t run a successful petition drive, then that raised questions in terms of how effective a representative you were going to be,” he told the Tribune in 2007.

The origins of this system can be traced back more than a century, to ballot reforms that began as an effort to limit the role of machine politics.

In the late 19th Century, unscrupulous political factions printed their own ballots and then paid, pressured or tricked people — often immigrants who spoke little English — into voting for those choices. Good-government advocates pushed for Illinois to join a wave of states that printed an official ballot, set up rules for who qualified and let people cast their votes in secret.

“So members of the machine, they don’t know who you voted for,” explained Twyla Blackmond Larnell, an associate political science professor at Loyola University Chicago.

Secret balloting, however, soon led to different forms of corruption, particularly in Illinois. In the mid- to late-20th century, the Democratic machine in certain Chicago precincts boosted vote tallies of favored candidates by filling out ballots for people on the rolls who hadn’t shown up to vote — sometimes because they were dead. An undercover Tribune investigation led to federal charges in the 1970s and helped shut down that type of corruption.

But state laws continue to offer powerful politicians another way to help control who gets into office: aggressive ballot challenges.

Federal courts can stop states from enacting laws so draconian they violate citizens’ right to ballot access. But the courts generally give lawmakers wide latitude, agreeing that states can have legitimate concerns about frivolous candidates. Illinois’ process has continually passed legal muster.

New York also allows candidates to try to kick rivals off the ballot, although one key difference is that New York typically requires fewer signatures on petitions. Running for mayor of New York City requires just one-third of the 12,500 signatures needed to run in Chicago, even though New York has triple the population.

Other places don’t encourage political rivals to attack opponents’ petitions. For example, in California elections officials, not rival candidates, vet the paperwork. If errors are found, candidates are allowed to correct them. And if some signatures get tossed, candidates get time to find replacements.

Illinois, however, chose a far different path.

A crushing exercise

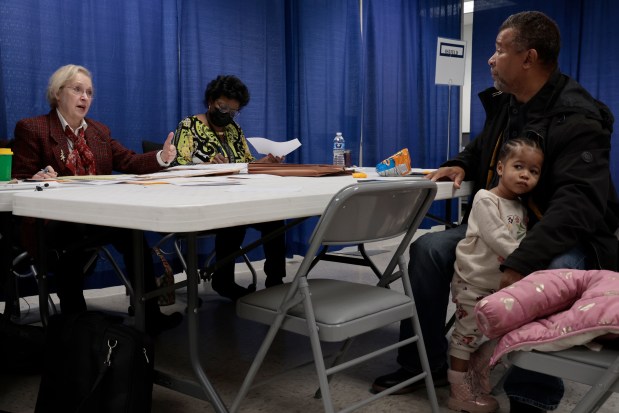

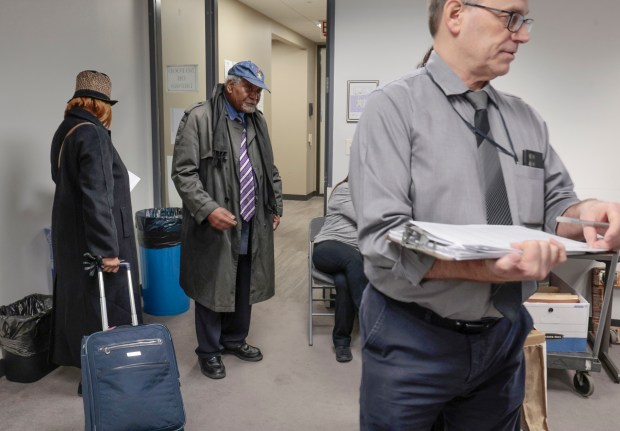

On a Monday morning a week before Christmas, hearings that help decide the course of Illinois democracy were playing out on two floors of the George W. Dunne Cook County Office Building at 69 W. Washington St., across from Daley Plaza.

In a basement conference room, and another room eight floors above, sat a series of rectangular folding tables, the kind you’d find at a church potluck, sandwiched together in sets of two to form makeshift courtrooms.

As candidates and lawyers came and went, the atmosphere felt relatively informal — like a mix of speed dating, traffic court and a law school reunion.

At one point, Davis could be spotted off to the side. Wearing a navy suit, the 14-term congressman sat on a folding chair next to a sample ballot box topped with a container of Clorox wipes.

The oldest member of Chicago’s congressional delegation was there because of Chicago Treasurer Melissa Conyears-Ervin, who wanted to take Davis’ seat in Congress. Her allies, aided by her husband, veteran West Side Ald. Jason Ervin, 28th, had filed challenges to Conyears-Ervin’s rivals on the Democratic primary ballot, including Davis.

In Davis’ case, the challenge was particularly startling: that Davis’ campaign workers had forged his signature on campaign paperwork. Doing that could be a felony, but the Davis campaign brushed off the allegation as a mere annoyance.

“They couldn’t find anything to really challenge the signatures (on my petition), so they came with this way-out notion of challenging my signature,” Davis told the Tribune, with the baritone chuckle of someone who’s survived more than four decades in Chicago politics.

Davis eventually testified, while sitting at one of the folding tables, that he did sign his own paperwork and did so in front of a notary as required. Davis’ attorney also had the congressman repeatedly sign a sheet of paper for later comparison to the signature on the paperwork.

The $200-an-hour hearing officer, a retired state appellate court judge, took it all very seriously. At one point he indicated for the record that Davis was signing his name on “orange-colored paper, eight-and-a-half by 11.” A court reporter documented that statement along with everything else said at the 32-minute hearing.

Davis’ case didn’t end that day, as the challenger’s attorney said he planned to produce an expert to prove Davis’ signature was a forgery. But Conyears-Ervin’s allies later dropped the challenge without ever calling witnesses or submitting any evidence.

The proxies who challenged Davis also filed challenges against Conyears-Ervin’s four other opponents, alleging, among other things, that many of the submitted voters’ signatures were “not genuine.”

With such complaints, the challenger’s goal is to get the reviewer to knock off enough signatures that the number falls below the amount needed to be on the ballot. Election employees are enlisted to go through each petition, page by page, line by line, to answer each challenge — which typically number in the hundreds.

After the review is completed, which can take hours over multiple days, the case goes back to a hearing officer, where attorneys can ask for more time to research legal issues or call witnesses. Often, thick stacks of legal briefs delve into the minutiae of election law for hearing officers who are under the gun to reach a recommendation before the ballot gets printed.

The exercise allows well-heeled operatives to tie up candidates for weeks, sometimes months, in what amounts to a barely hidden strategy to force rivals to spend time and cash to stay on the ballot, instead of using those resources to campaign.

When it’s all done, the hearing officer makes a formal recommendation to the elections board, which can accept or reject it.

The loser can appeal to the actual courts, where even a fast-tracked case can linger for weeks or months on the docket. Sometimes ballots are printed before the appeals are decided, resulting in mid-election changes that can be confusing for voters.

For Wilson, the whole exercise felt crushing. A public health and LGBTQ rights leader known by the nickname “Che Che,” Wilson said he could not spend the money for an election attorney and that he and his husband struggled to figure out the complicated rules and paperwork needed to become an official candidate.

In some ways, though, Wilson caught on quickly to how the game is played. After turning in his own paperwork, he challenged the signatures of another candidate running for the same job.

In the end, both Wilson and the other candidate got booted from the ballot because of challenges filed by allies of a third candidate, Laura Yepez. Nearly half of Wilson’s signatures were ruled invalid.

Yepez defended the ballot challenges, saying it’s fair to make sure candidates get the right number of acceptable signatures to prove they have broad community support.

“That’s just part of the process,” she said in an interview. “It’s always been part of the process.”

When primary voters viewed their ballot, there was only one choice for Democratic committeeperson — Yepez — in a ward with 44,250 registered voters living on Chicago’s Near Northwest Side, including parts of West Town, Wicker Park and Logan Square.

Discarded signatures

That lack of choice infuriated Allison Gossen.

Gossen told the Tribune she remembers Wilson coming to her Wicker Park apartment on a cold day last year, asking her to support his ability to run for the job. She was leery of opening her door but figured anyone willing to brave the weather for signatures deserved a shot on the ballot, so she signed.

But weeks later, Gossen’s signature was tossed after Yepez proxies alleged it wasn’t legitimate and a city elections board reviewer agreed it didn’t look close enough to the one on file. A second reviewer hired by the city affirmed Gossen’s signature should be removed from Wilson’s nominating petition.

Learning of those decisions left Gossen “so angry that both (the candidate’s) time and my time could be discarded with no real basis,” she said.

Rarely do petition signers know that one of their most basic acts of civic participation has been thwarted. Elections officials don’t send notification letters or emails to the voter, which could allow that person to submit proof the signature is legitimate. Gossen learned her signature had been rejected from Wilson while he was trying to persuade elections officials to reverse that decision.

The Tribune found signatures like Gossen’s are routinely tossed in a largely behind-the-scenes process where elections workers make snap decisions in assembly-line fashion using questionable methods.

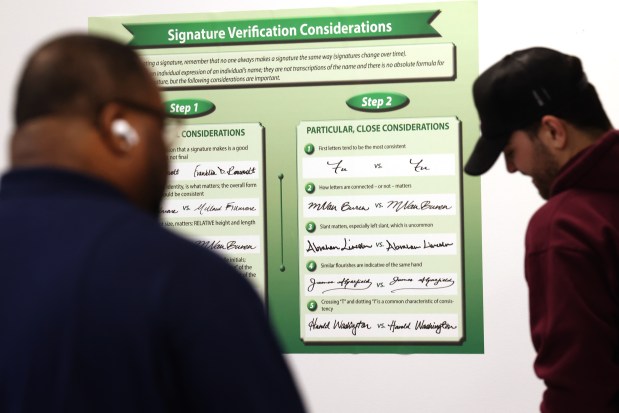

Each political cycle, elections board workers set aside their normal duties to become de facto handwriting analysts. In the Dunne building last December, the Tribune watched as a worker assigned to the elections agency’s District and Boundaries Division plowed through hundreds of signatures for newbie candidate Nikhil Bhatia, also running for Davis’ seat. Ald. Ervin sat across from the elections worker as a designated monitor for the proxies who filed the challenge in support of his wife, Conyears-Ervin.

For each challenged signature, the worker announced his verdict after 10 or so seconds of back-and-forth eyeballing between the scribbled name on the petition and the one on record, which was displayed on a computer screen. Then he moved on to the next signature. In that race, he tossed out more than half the challenged signatures.

On the other side of the table, Ervin followed along, signature by signature.

At one point, after the employee ruled a signature filed by Bhatia matched the one on record, the alderman complained, like a baseball manager arguing balls and strikes: “Are you looking at the same thing?” The elections worker replied with a monotone “Yes, sir” before moving onto the next signature.

Of the three major elections boards in the state that handle ballot challenges — the Chicago Board of Election Commissioners, the Cook County Board of Election Commissioners and the Illinois State Board of Elections — the Chicago board is unique. The city sends every contested signature, no matter what the elections worker decided, for another review by an outside contractor hired as a handwriting expert, arguing this second check helps ensure a correct ruling.

Those outside experts overturn many of the first decisions, underscoring the subjective nature of the process. A Tribune analysis of this year’s primary election cycle found the second reviewer overturned nearly one-fourth of the initial rejections, in essence deciding those signatures were legitimate after all. Conversely, about 6% of the signatures that passed muster with elections employees got rejected on the second pass.

In the end, out of roughly 10,200 signatures challenged as not genuine, nearly 1 in 4 were thrown out.

The state’s two other major elections boards rejected challenged signatures at similar rates: one in four tossed by the state elections board and 1 in 5 by Cook County’s elections board. All told, the three boards rejected roughly 4,000 signatures based solely on the belief they didn’t look similar enough to ones on file.

All of it is concerning to Linton Mohammed, an international expert in handwriting analysis. He’s testified as an expert witness in more than 250 trials and has helped lead both national groups for handwriting examiners: the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and the American Society of Questioned Document Examiners.

“You have election officials with minimal training, no magnifying glasses, no proper lighting and 30 seconds to make a decision,” said Mohammed, based outside San Diego. “That’s not a way to make a decision.”

Before each challenge cycle, city and county workers attend training sessions run by handwriting analysts, agency spokespeople said. The city sessions last about 90 minutes, while the county’s can stretch to two hours.

Mohammed said becoming a certified examiner takes three years and multiple exams. He also said he’d need one to two hours to do a good job vetting a signature.

Even for Chicago’s second-stage review, where the calls are made by outside reviewers considered to have more expertise in analyzing signatures, a Tribune analysis of invoices and data suggests the two hired reviewers took less than a minute, on average, to vet a signature. (Neither of those people responded to requests for interviews.)

In addition, Mohammed said anyone would struggle to make an accurate decision if all they had was one signature to compare to another – instead of a much larger sample of writing.

One reason for that is people’s signatures can vary with circumstances. A person’s scrawl when signing for a package might differ greatly from the careful signature that the same person writes on a will. Signatures can also change depending on whether someone is standing or sitting, what kind of pen they’re using, if they’ve lost motor skills as they’ve aged, or if — as with younger voters — they rarely write in cursive.

Given such variations, Mohammed said, it’s practically impossible to effectively compare a signature on a petition to one on a voter file.

“At one-to-one (comparison), it’s almost as if you’re guessing,” he said.

‘Perturbed and perplexed’

To be sure, there are good reasons to vet petition signatures, given Illinois’ rich history of political chicanery.

Stories abound of “round-tabling” — where a candidate’s supporters or hired guns sit around a table with a voter registration list, each forging a signature on a petition sheet before passing it to the next person. Even a suburban prosecutor was once caught doing it.

Illinois law, however, doesn’t offer specifics on how close a signature needs to be to one on file for it to be accepted. State Board of Elections spokesperson Matt Dietrich said its employees determine if there is a “reasonable match” between the signature on the petition and the one on the voter registration card.

The fickle nature of the process has been a common complaint over the years. Candidates have reported signatures from lifelong friends and from relatives were rejected as not genuine.

But most of the rejected signers are just regular folks like Brenda Hampton, of Maywood.

A registered voter in Cook County since 1982, Hampton has been signing her name to government forms for half a century. She was surprised to hear from a reporter that city officials decided her signature on a nominating petition wasn’t genuine.

“I was perturbed and perplexed why the signature had been disqualified,” said Hampton, who said she signed a petition for Kouri Marshall, one of the candidates for Davis’ congressional seat. “If I signed it, I signed it, and I know I signed it.”

Hampton, 73, said she’s sure she signs her name differently now than when she was coming of age in the Nixon administration and nobody’s ever told her that could be a problem.

“When I first started voting at age 18, I wrote one way,” she told the Tribune. “Well, 50 years later, my signature has changed. And so I would have assumed that I would have been notified that there was some question of the validity of my signature before.”

Election lawyers have acknowledged many legitimate signatures are rejected. While representing a candidate forced to endure a month of ballot hearings this year, Chicago election lawyer Andrew Finko urged the city elections board to ask state lawmakers to develop a new system for candidates to get on the ballot.

“We all know that hardly anybody uses a paper and pen, (and) I think few of us have checkbooks, so the signature standard is not the same gold standard of identity that it used to be in the 1930s or ’40s,” he told board members in January.

Elections officials have not made a significant push to alter the standards, although Cook County this fall is allowing suburban voters to update their official signatures on digital tablets at the polls, provided they show two forms of ID. City voters may get a similar option in future elections, but for now they must either show up at the elections office in the Loop with two forms of ID or mail in a form filled out in pen.

Candidates who think petition signatures were wrongly rejected can elevate the matter by gathering new evidence to present to the hearing officer in charge of the case. That typically means another round of hitting the pavement as candidates return to people listed as signing the petition in the first round and ask them to sign affidavits affirming they did so.

It’s a difficult process. The person has to be found and must be willing to sign an affidavit. And unlike with petition signatures, a notary must tag along to inspect the ID of the signer. Some candidates start this work even before elections officials rule on which signatures are valid — as an insurance policy of sorts.

Fearing her husband could get knocked off the ballot, Bhatia’s wife, Alison Ernst, spent hours traveling around the western suburbs on the afternoon of New Year’s Eve, armed with a clipboard and a notary in tow.

Snow flurries filled the air as the two women trudged up the steps to the Oak Park home of Bob and Jennifer Quinlan, who stood by their Christmas tree to fill out and sign affidavits.

Jennifer Quinlan called the process “infuriating” — that someone might claim her signature wasn’t really hers, that a government employee might agree, and that this kind of thing happens so often that it’s much harder for new candidates to take on the politically powerful.

“It’s sabotage,” she said. “It’s dirty politics.”

In the end, Ernst’s husband didn’t need the affidavits; Bhatia made the ballot without needing to present them. But other candidates have struggled with one last frustrating fact: Sometimes the hearing officer will reject an affidavit.

Elections officials explained that unless the affidavit gives a legitimate reason why the signatures on the petition and on the affidavit don’t match the signature on file, the document may not be sufficient to reinstate the signature.

In other words, somebody can sign a document swearing they are who they say they are, in front of a notary, and even present their driver’s license to the notary to prove it, yet still get their signature invalidated as not genuine.

It happened to Wilson, who turned in 110 affidavits in his doomed run for 1st Ward committeeperson. The case’s hearing officer rejected 73.

Among them was an affidavit signed by Raymond J. Rodriguez, who said he remembers signing Wilson’s petition last fall. After elections’ officials rejected Rodriguez’ signature, he assumed signing an affidavit would put the issue to rest. Then he learned from Wilson the affidavit also had been rejected.

“It’s very frustrating the amount of hoops that someone has to go through to prove it’s somebody’s signature,” he said. “I went through this (affidavit) to prove this is legit me, only for someone who I don’t know … to say, ‘Nah, that’s still not you.’”

Benefiting ‘the chosen’

Long before he faced federal corruption charges, Speaker Madigan was considered the most powerful politician in Illinois. Any potential law had to go through his House and through a Democratic majority he largely controlled.

Madigan had plenty of ways to reward loyalty to Democratic representatives who voted for him as speaker. He’d dole out campaign cash, lend political muscle and offer up plum committee assignments. But to help allies get and keep elected office, Madigan also mastered the art of ballot challenges. Loyalists could count on his chief elections attorney, Michael Kasper, to find ways to keep them on the ballot and their foes off.

One of the highest-profile election lawyers in the state, Kasper has represented hundreds of politicians at all levels of power, including helping Rahm Emanuel win a wild challenge over whether he could run for mayor of Chicago in 2011.

Kasper declined to comment for this story but has argued in court filings and in hearings that the law’s requirements protect against fraud and that the rules ultimately are up to lawmakers, not lawyers. He’s also defended Illinois’ ballot challenge system as “something to celebrate” because it allows anyone to file and defend against challenges, rather than relying on election workers to vet candidates’ paperwork, as in some states.

“We always get criticized here in Illinois because we have what the critics call a ‘Byzantine’ system,” Kasper was quoted as saying in a 2011 Chicago Sun-Times story. “But we have the best due-process system. Somebody challenges your signatures, you get to defend every single one of them as long as it takes.”

Cassidy recalled how Kasper would help House Democratic candidates with their nominating petitions — making sure they avoided all the “trip wires” written into state law to stymie candidates who weren’t “the chosen,” she said.

“It’s plug-and-play. It’s all prepped for you,” Cassidy said.

She said she also learned early in her career as a state lawmaker that Madigan’s legal team would challenge anyone who dared file papers against an incumbent in the caucus, including a Republican candidate in 2012 who had almost no chance in her heavily Democratic district.

“I did let them challenge somebody (who ran against her) once, early on, and I felt terrible about it,” Cassidy recalled. “I hated it. It was really a betrayal of my core values. But when it was presented, it was like, ‘OK. Here’s what’s going to happen. We’re doing this. You don’t have to worry about anything. You don’t even have to show up. This is what’s going to happen.’”

In the next election cycle, she said, she turned down Madigan’s offer to challenge an opponent.

“That was maybe the first time they’d ever heard that from anybody,” Cassidy said, “because they actually thought I was losing my mind. ‘Why would you pass up a free pass?’”

Others didn’t pass it up.

In 2014, Kasper was involved with at least two dozen challenges involving statehouse races. That included helping two of Madigan’s top lieutenants in the House — Edward Acevedo and Luis Arroyo — fight off challenges to their reelection paperwork. He also got their rivals kicked off the ballot. That meant voters in those districts only saw the names of Acevedo or Arroyo, as if no one else wanted their jobs.

Both Madigan allies kept their seats, then years later went to prison: Acevedo for cheating on his taxes while a lobbyist, and Arroyo for taking and passing bribes. Federal prosecutors have since tied Acevedo into the sprawling Madigan corruption probe, alleging in a recent trial involving the former head of AT&T Illinois that the utility paid Acevedo $2,500 a month for a no-show gig to curry favor with Madigan.

Left to watch from the sidelines was Antonio Mannings, a Republican who had filed paperwork to run against Acevedo in 2014. It would have been a difficult win in an overwhelmingly Democratic city, but Kasper still swatted him off the ballot.

Kasper’s challenge resulted in the city invalidating nearly three of every four signatures Mannings turned in, knocking him below the required threshold.

Now living in La Grange, Mannings recalled trying to insulate himself from such an attack by double-checking his petition signatures against voter registration information. Mannings also turned in 1,484 signatures, nearly triple the number he needed to make the ballot, to no avail. He said he also filed a challenge against Acevedo with the help of local GOP officials but didn’t succeed.

A decade later, Mannings still shakes his head at a process that he said needs to be overhauled. “You can essentially buy the election by challenging folks out,” he said.

Kasper also worked his magic in 2014 and 2016 to clear the ballot of referendums that would have asked voters if legislative redistricting should be taken out of the hands of politicians like Madigan. Kasper’s official clients were groups led by former Commonwealth Edison executives — one being John Hooker, a powerful ComEd lobbyist who also became ensnared in the Madigan corruption probe and who was convicted last year as part of the ComEd Four case.

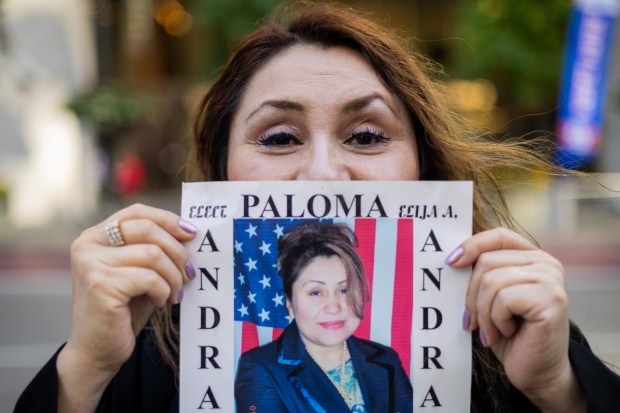

In 2007 Kasper used Illinois’ system to help another big political name who later fell from grace: Ald. Edward Burke, who was facing his first opponent in 36 years.

The ensuing legal debates created 995 pages of case records — including back-and-forth discussions over how close someone needed to be to a door to legally observe a person’s signature. The city elections board ruled opponent Paloma Andrade could stay on the ballot. Then the legal team for Burke persuaded a county judge to kick Andrade off the ballot. A higher court reversed that decision, but not until four days before the election.

By then, much of the damage was done, Andrade recalled to the Tribune. Burke’s army had already blanketed the ward saying a vote for her wouldn’t count.

In the end, she got just 10% of the vote.

Back in 2007, Burke defended the challenge as a noble effort to police the ballot, saying: “There’s laws that have to be complied with.”

Burke cruised to reelection, uncontested, in the next two races. Then federal wiretaps caught him offering to trade City Hall favors to get business for his law firm, starting a downfall that ended with a two-year prison sentence he started serving last month.

In a recent interview, Andrade said the 2007 race left her financially and emotionally drained. When federal prosecutors finally caught up to Burke so many years later, she was elated.

“I was waiting for this day for a long time,” she said. “And I say it’s finally going to come out that he’s the one who was corrupted, not me. He’s the one who tied me up in the courts and made me an example for my community to never run against a man like him.”

jmahr@chicagotribune.com

Tribune reporters Ray Long and Malavika Ramakrishnan contributed to this story.