Emma Grzesik of Maple Park was obsessed with horses. So, volunteering at Casey’s Safe Haven for service hours in high school was a natural fit.

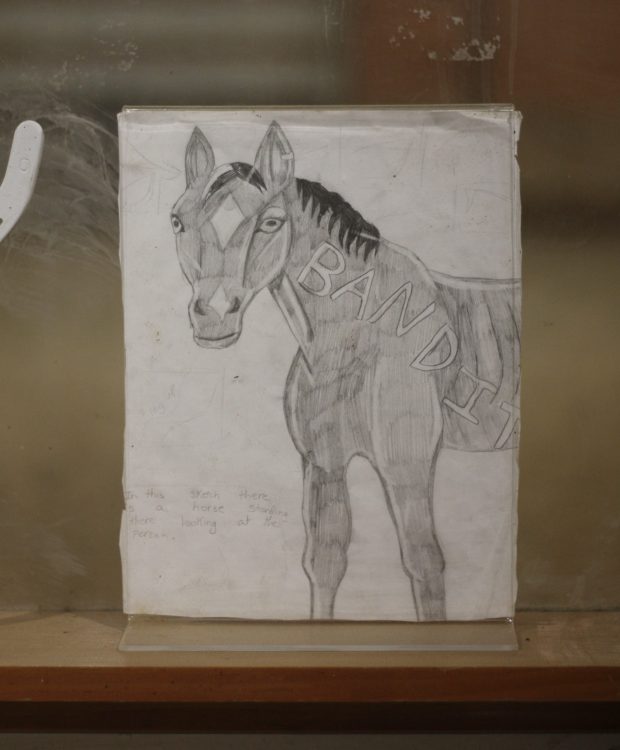

Grzesik had ADHD and autism. Her mother, Michelle Wollter, 47, said she was bullied in school, but had always found solace in horses – riding them, taking photos of them, drawing them.

“The first day she came home from (Casey’s), she’s like, ‘Mom, I found my place. I found my home,’” Wollter recalled.

Casey’s Safe Haven, founded in 2011, rescues horses, many with severe medical and behavioral issues due to neglect or mistreatment. The farm in Maple Park currently has about a dozen rescue horses. Six of those are miniature horses, several of which were taken in from pony ride facilities. They also have a donkey. Casey’s also houses some horses for their owners, for a boarding fee.

Because they take in animals with varied and complicated needs, those who work at Casey’s worry what would happen if they could no longer provide their services.

In December, Casey’s board of directors was informed that the owners of the property planned to sell, according to Mitchell Bornstein, 54, the head trainer and barn manager at Casey’s. The rescue currently rents its facility at the site.

The duties of volunteers and staff at Casey’s are wide-ranging. Since many of the horses have medical conditions, the rescue manages a variety of diets, medications and treatment plans for the animals, along with cleaning stalls and other tasks.

There’s a room inside the barn for employees filled with stacks of labeled food containers for each animal’s daily feedings and medications laid out along its counters. Volunteers aren’t allowed to handle feedings because of the strict dietary restrictions some of the horses have, according to Bornstein. Outside the horses’ stalls are white boards, a number of which are filled with directions on how to approach that particular animal.

Grzesik kept volunteering throughout high school, and was eventually offered a part-time job during her senior year. Wollter started volunteering there, too. During that time, Grzesik developed a special bond with one of Casey’s rescue horses, Bandit.

Soon after, Grzesik started attending Waubonsee Community College, with plans to become a graphic designer. She continued to work at Casey’s. Then, on April 30, 2024, she was killed at the age of 19 in a car crash on her way to school.

Wracked with grief, Wollter turned to Casey’s, just as she said her daughter had.

“Within a week of her passing, I knew I had to get back to the barn because Bandit – who Emma loved and who knew her – had been abandoned by his previous owners, because the one had died and the other had moved away,” Wollter said. “I didn’t want him to feel like he had been abandoned.”

She said her return didn’t just comfort Bandit, however.

“When I was with Bandit, I felt Emma,” she said.

Now, Casey’s has begun to make plans for what they’ll do if they can no longer stay at the property.

Ideally, Bornstein said, Casey’s would raise the money to buy the farm, which he figures could cost over $1 million. As a nonprofit organization, they currently finance their operational costs through donations, grants, events and boarding fees for some of the horses, he said.

Wollter started a fundraising campaign in an effort to raise the money they need, and they’re focused on trying to reach potential donors. But they face an uphill battle.

“Our fundraising has never risen remotely close to the level of what we’re talking about we need (to buy the property), forgetting our general operating costs, which we still have to fundraise for,” Bornstein said.

Information on donating to Casey’s is available at https://caseyssafehaven.org/.

If they don’t buy the property, Bornstein noted, they’d still face considerable costs to relocate, since it would require special transportation to move all of their animals.

And he worries relocating would disrupt much of the training he’s already done, particularly with the blind horses Casey’s cares for, who would have to learn the layout of a new barn. If they relocate and the organization can’t successfully move the horses, Bornstein said they may have to euthanize some of their animals.

“It’s not like we’re a mom and a dad and their two kids that could pack up a suitcase and call a moving truck,” he said. “It doesn’t work like that in this type of operation.”

Bornstein came to run the facilities at Casey’s through Prince, a stallion with serious behavioral and training issues. Casey’s took the horse in, and just weeks later in summer 2020, they called Bornstein to help train him. Since Prince had attacked people several times already, he thinks the rescue might have had to euthanize the horse had they not been able to find a way to train him.

Bornstein has his own horse training business, the Art of Horsemanship, so he continues to train horses at other barns, but he took on greater responsibilities over time at Casey’s as he worked with Prince. He now manages the barn in addition to training the horses.

About four times a week, Bornstein is at the barn working with Prince and overseeing the rest of the animals. In the riding arena with Prince, he alternates between riding and lunging, a training method where the horse moves around the trainer in circles on a long rein.

“If I can move you right or left, I am your boss,” Bornstein said, crediting much of Prince’s behavioral progress to the rigid training regimen.

But he called Prince a “bully,” even now, and said he doesn’t allow volunteers or full-time staff to interact with Prince.

“Every time you are near a horse, you teach a horse,” Bornstein said.

Casey’s has one full-time groom, who cleans the barn, along with a few other full-time staff, who manage the barn’s operations and administer medications. They also have a host of regular volunteers, who clean the facility and do administrative tasks.

And Bornstein and Wollter worry what would happen if a place like Casey’s disappeared – to both the animals and the people who work there.

“Animals are healing, and animals are accepting, much more so than people,” Bornstein said, saying he has prioritized hiring people with disabilities as staff and volunteers. “I make an effort to offer positions to people who, maybe, are looked over and passed over in other facilities because of issues that people think are problematic (for working with horses).”

Grzesik was a prime example, he said.

“We have a barn full of damaged animals who could take weeks and months to open up normally to our people,” Bornstein said. “On the first afternoon, they were cuddling with (Grzesik) and everything – a lot of them, of our really difficult ones. We allowed her access to some of the animals that I don’t allow anyone access to here, because of the way they are. She was interacting with them like I do.”

Wollter still volunteers at Casey’s, and joined the board of directors in October. Now, she says she’s trying to preserve the rescue for her sake, her daughter’s sake and for the people who might benefit from it in the future.

“I know with Emma’s passing that Casey’s can’t be there for her anymore, but they’re there for me,” Wollter said. “Even though it’s not gonna be there for Emma, it can be there for somebody who’s like Emma.”

mmorrow@chicagotribune.com