Chicago’s top migrant official is walking back a prediction from city leaders last month that tens of thousands of migrants would arrive by bus ahead of next week’s Democratic National Convention, saying that there is no “credible intel” that the feared surge will occur.

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s deputy mayor for immigration, Beatriz Ponce de León, told reporters in July the city was preparing for as many as 25,000 migrant arrivals tied to the DNC. But President Joe Biden’s June executive order limiting asylum-seekers’ arrivals at the U.S. border has sharply changed the city’s expectations, she said.

No migrant buses have come to Chicago since June 17, according to Brian Berg, spokesman for the city’s Department of Family and Support Services.

“We at this point do not have any credible intel that there will be a large surge in terms of buses coming from Texas,” Ponce de León told the Tribune Tuesday.

City officials had feared in the lead-up to the DNC that Texas Republican Gov. Greg Abbott would use the gathering of Democrats as a political opportunity to send a barrage of buses to Chicago to overwhelm the city’s migrant infrastructure. Chicago has received 46,418 migrants seeking asylum since August 2022, many of them arriving in nearly 1,000 buses sent by Abbott.

Abbott had promised during the Republican National Convention in July that “those buses will continue to roll until we finally secure our border.” A week later, Chicago officials presented to the City Council how they planned to respond to the “fully expected” 25,000 surge. Ponce de León reiterated the high-end estimate to reporters after the meeting, but noted the number was “all speculation.”

Ponce de León told the Tribune that the July estimate had been based on the number of migrants coming to Chicago at the height of the city’s migrant crisis over the past winter — sometimes more than 2,000 arriving in a week. When asked why the city based its calculations on that period of time, officials said they looked at a number of possible arrival projections to be prepared for any situation.

But as the time for speculation wound down the week before the convention, Ponce de León said Johnson’s administration has no reason to believe anything will change in the next week, though she warned that city officials have no control over how many asylum-seekers could come to Chicago.

In early June, Biden’s executive order significantly limited asylum-seeker arrivals. While migrants continue to make their way to the United States, immigration authorities are now denying anyone who illegally crosses the border a chance to apply for asylum, leading to plummeting crossings in July.

And though the executive order is being challenged in court, briefs for the case will not be filed until Sept. 10, over two weeks after the DNC is over.

“There just aren’t that many people to send,” said Stephen Yale-Loehr, professor of immigration law practice at Cornell Law School.

Immigration experts and those working along the border had been skeptical of the surge predicted by the city.

“Abbott would have to send a lot of buses into Mexico, load them up in Mexico, then bring them across himself,” said Ruben Garcia, who runs several shelters for asylum-seekers in El Paso, Texas.

Still, dozens of migrants continue to arrive in Chicago every day. From July 13 to Aug. 11, the average number of new arrivals per week has been 157 individuals, according to city data. Migrants arriving now are generally making their own way to the city, Ponce de León said.

Even as migrants arrive, the number of people living in Chicago migrant shelters continues to steadily decline. There are 5,579 people living in the city’s migrant temporary housing shelters, almost a third of the December count and the lowest population since the city began sharing such data almost a year ago.

The city has nearly half of its shelter capacity available and has plans in place with the federal, state and county governments to set up “just-in-time” shelters if more beds are needed should a surge occur, Ponce de León added.

City makes case for “humanitarian” but expensive response

Republicans have zeroed in on immigration, a top election issue for voters, to blast Democrats in recent weeks. They argue allowing migrants into the United States and supporting them pulls jobs and money that would otherwise go to citizens.

It is a point Chicago leaders know well. And it’s one that they are challenging as national attention falls on the city and the $460 million effort it has taken to feed, house and care for newcomers.

“Rather than turn our backs and let people fend for themselves, we made a decision to make sure that people did not become unsheltered and become homeless and live on the street. I think that is something to be proud of,” Ponce de León said.

Ponce de León, who herself was born in Chicago to immigrant parents who’d overstayed their visas, said Chicago’s “humanitarian approach” also adds population growth that could help its economy grow long term. The effort has also made the city ready for future mass migrations.

But the issue has divided aldermen across the city.

Some aldermen, along with volunteers working with migrants, say the city is not doing enough for asylum-seekers. They point to Chicago’s shelter stay policy, which asks asylum-seekers to leave after 60 days before being allowed to reapply for shelter beds.

Meanwhile, other aldermen believe too much has been spent on migrants and not enough on underserved Chicago communities.

“As much as our heart goes out, we’re not seeing it in our community,” Ald. David Moore, 17th, said as the City Council approved another $70 million in migrant spending in April. In the same meeting, the council passed Johnson’s $1.25 billion Chicago-focused bond plan largely earmarked for affordable housing.

And even with millions of dollars in taxpayer money toward the cause, migrants have told the Tribune they aren’t receiving help from shelter staffers and have faced supply rations.

When asked what is the most pressing challenge in the migrant response now, Ponce De León acknowledged that there have been local challenges, but pointed her finger toward federal immigration policies.

“The biggest concern is work authorization,” she said. “If people were able to work, they would much more quickly move out of shelters and be able to become self-supporting.”

She said Chicago’s migrant response goes further than other cities that have received large numbers of migrants. Denver caps their shelter stays for new arrivals at 72 hours, but also recently began offering rental assistance with job assistance and skill training. Adults in New York are limited to 30 days without a chance to reapply for shelter.

Wilmette volunteers still brace for potential arrivals

During the peak of border crossings last fall and winter, Chicago received several buses daily. To curb and control arrivals, city officials passed an ordinance penalizing and fining buses for dropping off people at unannounced hours.

For several months afterward, a steady stream of migrants would get dropped off in the suburbs and take trains into the city. Many came from Venezuela amid a political crisis, worsening now after a disputed late-July election.

Dozens of suburban municipalities enacted similar restrictions to Chicago’s to stop buses from coming, especially in the middle of the night.

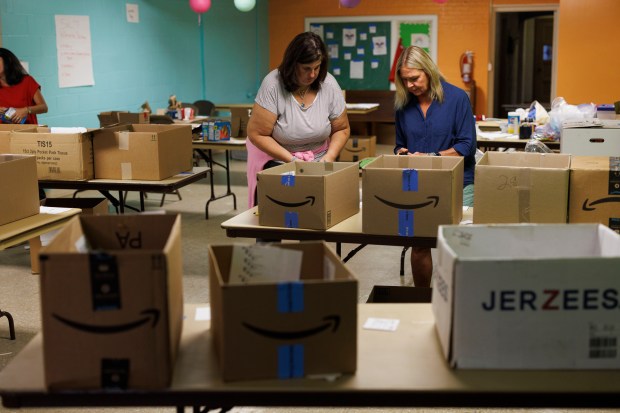

This week, volunteers in Wilmette — one of the last suburbs to pass an ordinance — are still preparing for hundreds of migrants to come to the city before next week’s DNC. They’ve spent days assembling 1,000 welcome bags for migrants in a church basement.

“It’s not like Texas is going to send up a flag like, ‘Here they come!’” volunteer Heather Oliver, 53, said Monday as she organized first-aid supplies with other volunteers. “But it would be naive for us not to be prepared.”

Wilmette police Sgt. Roger Ockrim said Texas officials do not communicate with suburban police.

“Nobody knows,” he said.

Ockrim, who has been an officer for 26 years, said he talked with a few recently arrived migrants in Wilmette and was struck by their stories of traversing countries for a better future.

“What stages of your life do you have to be in that this is what you’re willing to do? What does that say about where you came from?” he asked. “And how do you not open your arms to somebody?”

Volunteers had not heard any updates as of Wednesday afternoon.