Looking back in her journal from five years ago, Vidya Mandiyan uses the word “surreal” to describe what it was like as chief of internal medicine at Rush Copley Medical Center in Aurora when the pandemic hit.

The first COVID-19 case through the hospital doors was March 18, 2020. And just like that, the Aurora doctor found herself on the front lines of a health crisis that upended society and turned her own life into a “whirlwind.”

“People were getting sick so quickly you did not have time to think,” Mandiyan recalled. “We did not know enough about the disease … all we could do was take the information and do the best we could.”

Likewise, Yvette Saba, president of Edward Hospital in Naperville, also used “surreal” while recalling that time when “all you focused on 24 hours a day was taking care of patients and staff.

“You had to be dynamic and flexible,” she added, “ready to adapt at whatever hit.”

And when exhaustion set in, or fear would begin to take hold, they remembered pushing aside those concerns because people’s lives were at stake and a community depended on them.

“We practice to be prepared for emergencies and disasters,” said Saba. “This was a real live one that lasted a long time.”

Far longer than most anticipated.

“It was the most trying thing we’ve been through,” said Michael Isaacson, executive director of the Kane County Health Department, which was responsible for coordinating critical partnerships between hospitals, health care agencies, schools, law enforcement, shelters and churches as the community faced this unprecedented time in history.

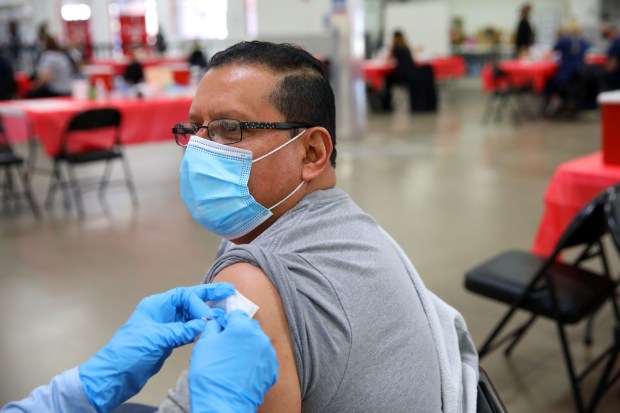

Victor Torres receives a Moderna COVID-19 vaccine March 19, 2021, in Batavia at Kane County’s COVID-19 mass vaccination site. (Stacey Wescott / Chicago Tribune)

Consider the fact that at one time, there were over 100,000 people on a waiting list to receive a vaccination, and in the end, Isaacson said, the health department worked with other agencies to provide over 200,000 vaccines.

Dr. Jonathan Pinski, medical director of infection control and prevention at Edward Hospital, repeatedly used “intense” when I asked about the pandemic. But he also recalls his experience in the trenches as “humbling to just provide comfort” when little else would work.

In so many ways, Pinski told me, he felt “like it was 20 years ago” when he was a “doctor in training,” going through that “same level of stress” while coping with so much new information.

And yes, he remembers being “really tired,” particularly at first when “all we could offer was oxygen and prayer.” Even later in the pandemic, however, new challenges presented themselves, he continued, including how best to treat those who had grown mistrustful of medicine.

Reflecting back, Pinksi believes he became a better doctor, not only because he gained appreciation for “the fragility of life and how it can change on a dime,” but because he learned more about “how evidence-based medicine works.”

Spending more more time viewing the latest literature, he admitted, made him “a better physician scholar.”

There’s no question the pandemic left a lasting impact on the health of our communities.

Eric Ward, executive director of Family Counseling Services, blames COVID-19 for the rise in mental health issues, particularly among our youth. Joe Jackson, executive director of Hesed House in Aurora, sees it, as well, noting that “levels of mental and behavioral health issues are at the highest level we have ever seen by far.”

The homeless shelter, too, is “starting to see it in young people, in any demographics, whose lives are upside down” because of anxiety, depression and substance abuse issues, Jackson added.

This crisis is the reason, Isaacson says, the health department is putting more focus on mental health initiatives, including the February launch of Behavioral Health 360, a comprehensive online platform designed to provide 24/7 support for those facing these struggles.

Still, there’s no question getting access to appropriate behavioral health services continues to be a problem, which is why the health department’s goal is to continue increasing screening and intervention services to meet that growing demand, Isaacson said.

Edward Hospital’s Saba blames the physical and mental toll the pandemic took on employees for the decline in bedside clinicians. “It changed people,” she said, adding that nurses in particular retired or left the field because they were exhausted.

“And we are still trying to play catch-up,” Saba said, “but it has taken a lot of effort to refill the pipeline.”

Likewise, Jackson is bothered by how much “institutional knowledge” was lost when shelter staff members with 10 or more years “decided to step away when things became too dangerous.”

Also, he added, while the number of churches partnering with the Aurora homeless shelter have remained the same, individual volunteers are not fully back.

“I would argue that the pandemic changed just about every facet of how we operate,” he said, noting how the shelter’s cleaning protocols were changed from one a day to multiple cleanings and sanitizations daily.

Plus, there’s now more emphasis on its capacity numbers and social distancing, which in turn created the need for a $4.5 million expansion project that was completed last year.

Rush Copley’s Mandiyan says she worries about the long-term impact COVID-19 has physically on the body, something she says that “will not be known for decades.” She also suggested that, while we’ve made advances on how to treat those who get sick, “we must do better prevention. And that is going to take time.”

Still, there have been positive changes, including how we approach respiratory disease, say these health experts, referring to the development and deployment of vaccines and antiviral medicines, the use of noninvasive ventilation and isolation periods.

“There were a lot of things we had to figure out,” said Saba. “Medicine changes and we need to adapt.”

Which is why, even though this virus has yet to adapt to humans, “all have eyes on the bird flu,” noted Pinski. “Things are safer. It is easier to relax, but the moment danger comes, all attitudes change.”

Still, there is reason to celebrate five years after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts insist.

“So many people made sacrifices,” Pinski pointed out, while also asking “how many more lives would have been lost” if frontline workers had not shown up to do their job and if others had not stayed home when it was unsafe to gather.

Heroism was evident in so many ways. But so also was cooperation – from the public, who stepped up to support health care workers and from the many organizations that put aside their own agendas to work closely with each other in this time of crisis.

“I do think partnerships are why we did as well as we did,” said Rush Copley’s Mandiyan.

Isaacson agreed, adding that these critical collaborations not only came together during the pandemic but have remained firmly in place.

“While there are always ways to improve, I think we have the right pieces in place,” he said. “As painful as it was, we were fortunate to live in a time and place where access to scientific abilities allowed us to quickly create the vaccine, which saved lives.

“I’d rather be alive now and here in the Chicago area than any other place.”

Saba, from Edward Hospital, concurred.

“Every disaster you take something away from it,” she said. “We will be a lot more prepared if another one hits.”

dcrosby@tribpub.com