When he looks back on his 45-game stint as interim manager of the Chicago White Sox, Grady Sizemore can remember Aug. 14 as a red-letter day.

That was the night Sizemore ordered an intentional walk to Juan Soto to face likely American League Most Valuable Player Aaron Judge in the eighth inning of Wednesday’s 10-2 loss to the New York Yankees.

It was a “pick your poison” moment, as Sizemore noted more than once afterward, pointing to the four home runs Soto had hit off Sox pitching in two games. If Judge isn’t the best hitter in baseball right now, it’s hard to argue against Soto being The Man.

Even so, Sizemore likely will go down as the only manager in 2024 to call for an intentional walk to face a player on pace to hit more than 60 home runs for the second time in three years. Judge lined a 3-0 pitch over the wall in left for his 300th career homer, reaching that plateau quicker than any player in major-league history.

It was one of those rare moments at Guaranteed Rate Field when “South Side, stand up!” actually happened. Sox fans joined Yankees fans in standing and saluting Judge for his milepost homer. A close game was already out of reach for the Sox, and Sizemore’s decision led to a moment they’ll remember forever.

For Sizemore, it was a proper way of reintroducing himself to a national audience that may have forgotten his 10-year playing career, which ended in 2015 and included a Sports Illustrated cover in 2007 with the title “Why Sizemore matters.” The subhead included this declaration: “He’s without a doubt one of the greatest players of our generation.”

Sizemore was 24 then and a budding superstar in Cleveland, but the hype didn’t last. A series of injuries shortened his career, though not before he’d made enough money to enjoy a life of ease, watching his three young children grow up in Arizona.

“Me and my wife were just starting to have kids, so I spent that time just with the family,” he said of retirement. “Every day, not missing a thing. Just trying to be there, have fun and watch them grow up.”

How Sizemore got from that point to managing a White Sox team on track to break the 1962 New York Mets’ record of 120 losses is a long, strange story that’s hard to believe, even in this age of microwavable managers who are hired without any prior experience.

Pedro Grifol’s days had been numbered since a 3-22 start in April, but no one could have envisioned his replacement would be Sizemore. Bench coach Charlie Montoyo had managed in Toronto. Triple-A Charlotte manager Justin Jirschele is the son of former Kanas City Royals coach Mike Jirschele, a favorite of Sox general manager Chris Getz. Even the return of Sox shaman Tony La Russa made more sense than someone with Sizemore’s resume.

But at some point in the last month, Getz decided to jettison Montoyo as part of the eventual Grifol sacking, and when he pulled the trigger Aug. 8, he shockingly called on Sizemore to try to steer the Titanic away from the ’62 Mets iceberg.

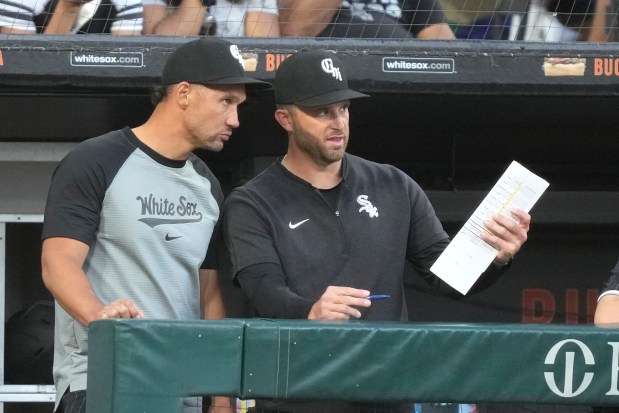

“Never saw that coming,” Sizemore said at his introductory news conference, conducted in the Sox dugout with Getz at his side.

Sizemore said managing was never on his radar, and he didn’t enjoy talking to the media as a player. He claimed to have a fear of TV cameras and of saying the wrong thing. But here he was in the media spotlight, taking over the worst team in baseball while knowing he wouldn’t be considered for the job in 2025.

So how did it happen?

Getz never explained why Montoyo wasn’t considered, instead talking of the “respect” Sox players had for Sizemore, who interviewed well.

“He spoke of some of the better coaches and best managers he was around, (and) a lot of them it was because they were authentic, real, honest,” Getz said. “And Grady, he presents that on a daily basis. It’s very natural for him.

“As I observed that, as I was around it more and made this decision to make this change, it just seemed like the right fit currently, knowing we’ve got seven weeks left in the season.”

Grifol inadvertently bought himself some time during an AL-record-tying 21-game losing streak that ended Aug. 6 in Oakland. There was no reason to saddle a new manager with that extra baggage, so Getz waited until they finally won a game before making the change two days later.

Sizemore came to the Sox last winter at the suggestion of assistant GM Josh Barfield, who was friends with him in Arizona. Barfield, then the Arizona Diamondbacks director of player development, introduced Sizemore in 2021 to D-backs outfielder Trayce Thompson, and the two hit it off. Sizemore started following Thompson’s career, offering tips.

“He was Mr. Mom, taking care of the kids,” Barfield said. “Grady is a big homebody, so I thought because of that he wouldn’t want to come back to the game. He started following some of our players’ at-bats and telling me what he saw. I said, ‘Man, you’ve got the bug.’”

D-backs GM Mike Hazen offered Sizemore a coaching internship in 2023. He was limited to 40 hours or less per week and made $15 an hour working in the Arizona Complex League. When Getz hired Barfield last winter, Barfield recommended Sizemore for a coaching spot.

“He interviewed really well, and everyone was like, ‘We’ve got to get this guy,’” Barfield said.

For six months, from spring training to August, Sizemore was virtually anonymous as a Sox coach, often seen shagging flies with players in batting practice. If you didn’t know he was Grady Sizemore, you would have mistaken him for a Sox player. He’s 42 but could pass for mid-30s and has the same physique as in his playing days. Sizemore didn’t speak to the media, and they had no reason to speak to him. He was basically invisible.

What were his duties?

“I tried to just help out any way I could,” he said, pointing to outfield defense, baserunning and hitting. “I was just trying to learn too. I was around Pedro and those guys just trying to pick up anything I could and be an extra helping hand anywhere that I was needed.”

None of those three categories has been a strength of the ‘24 Sox, who have been the worst-hitting team in the majors for months. So it’s hard to speculate on what stood out in Sizemore’s coaching that made Getz decide he could manage.

Regardless, a promotion to interim manager was in the cards. The Sox begin a six-game trip Friday in Houston, and Sizemore is 1-4 managing a team that could reach 100 losses before the end of August. He’ll be the primary spokesman the next six weeks as they chase the ’62 Mets’ record of infamy.

“I don’t think anyone in this organization wants to be associated with a record we could potentially have,” Getz said.

Getz insisted avoiding the record isn’t “our highest priority,” or else they wouldn’t have dealt quality players such as Dylan Cease, Erick Fedde and Michael Kopech.

Still, it will become a national story the closer the Sox get to the ’62 Mets. They need 14 wins in their last 40 games to avoid it, a .350 winning percentage the rest of the way. Their current winning percentage is .238 (29-93).

Sizemore is learning on the job, and Getz said it would be a “group” effort with the rest of the coaching staff. Asked about his approach to analytics, Sizemore said: “I tend to be a little more old-school. We have professionals for that, guys who have specialized in that. I tell them to give me everything and tell me your thoughts. But I try to look at it, take all the information and just use my strengths to apply it to the team.”

Perhaps it was an old-school “gut feeling” that told him to intentionally walk Soto to get to Judge in what looks to be a historic offensive season for the Yankees slugger. Who knows?

Judge said he was “fueled” by the intentional walk to Soto, though he understood the rationale.

“It locks you in, but I get why he did it,” Judge said. “The way Juan’s been swinging the bat and what he’s done in this series, four homers, driving the ball all over the park, I’d probably walk him too in that situation.”

From taking the kids to school to trying to figure out a way to stop Soto and Judge, it has been quite the trip for the former Mr. Mom.

There should be more in store these next few weeks.

Sizemore’s journey is really just beginning.