The vice-presidential debate has been widely – and rightly – applauded. Democratic Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota and Republican Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio behaved like two adults.

Their generally polite and serious interchange contrasts with the presidential candidates’ debate, which was characterized by highly personal attacks and shamelessly biased moderators.

Here, as elsewhere in national politics, context is important.

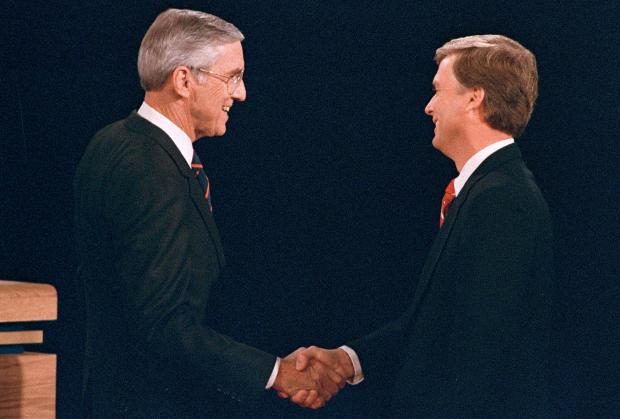

Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, D-Texas, left, shakes hands with Sen. Dan Quayle, R-Ind., before the start of their vice presidential debate at the Omaha Civic Auditorium, Omaha, Neb., Oct. 5, 1988. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

The conventional wisdom is that vice presidential debates have not really mattered much. The important contest, from this perspective, is between the heavyweight contenders at the top of each party’s ticket.

Even a devastatingly one-sided exchange, for example in 1988 between formidable Democratic Sen. Lloyd Bentsen of Texas and ineffective Sen. Dan Quayle of Indiana, did not fundamentally affect the election. Vice President George H.W. Bush and Quayle defeated Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis and Bentsen.

However, actual political dynamics are more complex. The evolution of televised political debates since 1960 reflects, indirectly but powerfully, the importance of the modern vice presidency. For the expansion of that office, most of the credit should go to one particularly controversial occupant – Richard M. Nixon.

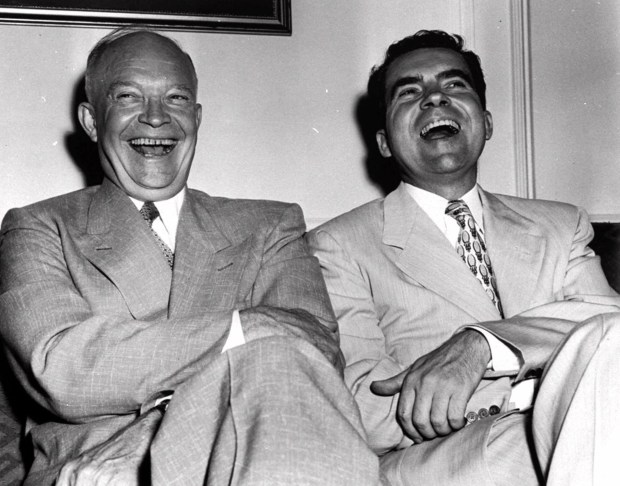

Nixon’s political road was never easy, partly because of his own self-defeating ways, partly because of other circumstances. Dwight Eisenhower effectively but subtly promoted him among Republican convention delegates as his running mate in 1952, but then used a controversy over alleged misuse of campaign money to try indirectly to get him off the ticket. Four years later, he more politely suggested Nixon move to a cabinet position, ostensibly to further his presidential aspirations.

Throughout, Nixon hung in there, working relentlessly to build a formidable grassroots base of support and a reputation for significant foreign policy expertise. In 1960, when East Coast political backers of Ike looked to Gov. Nelson Rockefeller of New York to secure the Republican presidential nomination, Nixon decisively defeated them.

John Nance Garner of Texas, who suffered as vice president under FDR, declared crudely that the office was not worth “a pitcher of warm spit.” Nixon changed that, bringing the importance of the post in line with the reality that a number of vice presidents have in fact succeeded to the presidency.

Richard Nixon also deserves considerable credit for agreeing in 1960 to debate the Democratic nominee, Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts. Kennedy observed privately that otherwise he could not have won.

Conservatives, prominent in radio and other media, complain about liberal dominance of the media. Sixty-four years ago, working reporters generally were Democrats, if not liberals, and many had a special dislike for “Tricky Dick.”

Nixon debated anyway.

The Kennedy-Nixon legacy of debate became firmly established and broadened with the 1976 debates between Republican President Gerald Ford and Democratic nominee former Gov. Jimmy Carter of Georgia, plus vice presidential nominees Sens. Robert Dole of Kansas and Walter Mondale of Minnesota. Dole’s angry, slashing attacks about “Democrat wars” contributed to the Republican election loss in November.

During the 1990s, Al Gore’s relative effectiveness in campaign debate helped position him to secure the 2000 Democratic presidential nomination.

Richard Nixon in his final years regularly was visited by aspiring young Republican politicians. When asked about controversy, he invariably replied that controversy could be helpful.

Worry instead about being boring – when voters lose interest, you’re finished.

Thank Nixon for helping to keep us engaged. The recent debates, however flawed, were not boring.

Also, thank Gerald Ford for the fairness that led him to agree to debates. Nixon selected Ford to be vice president in the midst of the Watergate crisis, so thank him again.

Arthur I. Cyr is the author of “After the Cold War” (NYU Press and Palgrave/Macmillan).

Contact acyr@carthage.edu