Short in physical stature but a giant in his time, Abe Saperstein created in Chicago that international sensation called the Harlem Globetrotters.

That remains his most notable and influential accomplishment but this was a man of inexhaustible energy and ideas. You can add to that achievement such others as pioneering the three-point shot; heightening basketball’s popularity across the country and planet; promoting an array of talents, from musicians to movie stars, from the Ice Capades to a French portrait painter; working with baseball’s Bill Veeck and others to break major league baseball’s color barrier and promote pitcher Satchel Paige; and rescuing Olympic star Jesse Owens from poverty.

All of that — but wait, there’s more — earns this 5-foot, 3-inch man a place alongside such people as George Halas and only a few other Chicagoans in the pantheon of sports and entertainment marvels of the 20th century.

Born on July 4, 1902, in the London neighborhood of Whitechapel, Saperstein died on March 15, 1966, in Weiss Memorial Hospital here. His 63 years were filled with so much activity that it is mysteriously astonishing that there has never been a full-blown biography. That surely would have saddened and surprised him, for in his lifetime he was a fabulist of the first rank, creating in the press favorable stories about himself, the Globetrotters and his many other endeavors.

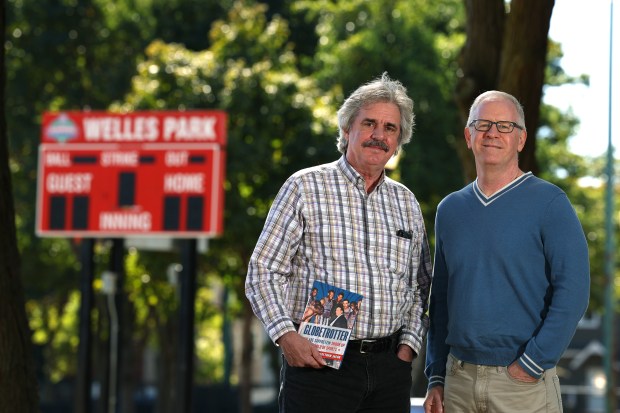

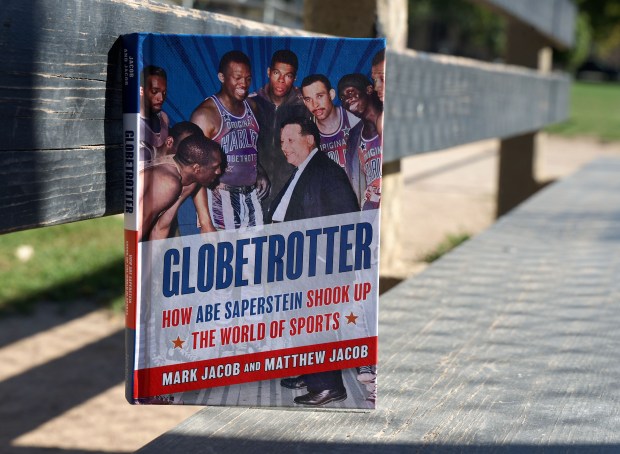

That injustice has finally been remedied by brothers Mark and Matthew Jacob in their deeply researched, exquisitely written new book, “Globetrotter: How Abe Saperstein Shook Up the World of Sports” (Rowman & Littlefield).

Mark was formerly a longtime journalist with the Sun-Times and Tribune, where he was a high-ranking editor. Matthew was a journalist for a time before becoming a public health consultant based in Virginia. They previously collaborated on 2010’s “What the Great Ate: A Curious History of Food and Fame” and Mark is the author of a number of books and a lively media and politics newsletter, and is the editor of the new book “Everybody Needs an Editor.”

The pair had been looking around for a new project when the idea for this one came from their friend Richard Cahan, a local photographer, author and publisher.

Admitting that their subject’s “legacy is complicated,” the brothers have written what is surely the definitive story of Saperstein, and a fabulous one. They rightly call him “the 20th-century version of P.T. Barnum.”

He arrived here as the 5-year-old son of a father who was a tailor in a family that would number nine children. An enthusiastic and talented athlete, he graduated from Lake View High School and worked a number of odd jobs until he was hired at 24 as a public employee at Welles Park, where he had often played sports. There he began coaching basketball and that would lead to the formation of the Globetrotters.

The book details that road, a roller coaster on a shoestring, with Saperstein and five Black players traveling in (and often forced to sleep in) a Ford Model T, with the shadow of race ever present with, as the Jacob brothers write, “a Jewish guy and five Black athletes rolling into predominantly white rural towns where some residents had never even seen a Jew or a Black person face-to-face.”

These early years are captured in compelling detail, and then things take flight with a 1948 game between the Globetrotters and the Minneapolis Lakers and their star George Mikan at the Chicago Stadium.

Increasingly successful, Saperstein soon hired 7-foot college star Wilt Chamberlain, having failed to grab that other college sensation, Bill Russell, who would eventually sign with the Boston Celtics but not before jabbing the Globetrotters with, “I don’t want to be a basketball clown.”

But that clowning was a great appeal of the Globetrotters, embellishing the players’ high-flying talents.

At the start, neither of the Jacob brothers knew much beyond some modest details of Saperstein’s story but they were excited by their journey.

“We immediately realized how little we knew of him. And though I may have written more of the book, I gave Matthew the hard parts,” Mark says.

“I did a lot of the research and Mark most of the interviews,” Matthew says. “We would exchange chapters, talk frequently, never really arguing. Our writing styles are pretty similar.”

Early on, they refer to Saperstein as a “human dynamo” and the following pages offer ample proof. They write that he “didn’t make it easy for biographies, but he sure made it interesting.”

They write that their subject is a “tangle of contradictions, myths, mysteries, mistakes and triumphs … the story of a force of nature who crashed through life, making a spectacular impact.”

Indeed. Some see Saperstein today as having promoted demeaning racial stereotypes. Others gave him and his Globetrotters their due — in 1978 Jesse Jackson said, “I think they’ve been a positive influence. They did not show Blacks as stupid. On the contrary, they were shown as superior.”

Jonathan Eig, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “King: A Life,” says the Jacob brothers’ book “dazzles with its fine writing and scores over and over again with its impressive research.” Robert Kurson, author of “Shadow Divers,” calls it a biography of a man “whose impact on American athletics, race relations, and flat-out fun remains as vibrant and valuable as ever.”

Some may not come away from this book with unbridled affection for Saperstein. He was not, for instance, a loyal husband to his wife Sylvia. As one of his brothers put it, “His only vice was women — lots of them! He had women stashed all over the world.”

He wound up visiting 90 countries in his lifetime, falling 10 short of his 100-country ambitions. But he gave millions of fans “a brief escape from the everyday.”

The Jacob brothers appreciate that and they are undeniably fascinated with the man. They have unearthed invaluable numbers of facts, such as this bit of self-assessment from their subject’s mouth: “I’ve been wrong. At times I’ve been crazy. The trick in life, though, is to keep venturing and hope that you’ll be right more times than you’re crazy.”

What a guy. What a book.

rkogan@chicagotribune.com