At lunchtime earlier this week, Lester Munson could be found at Wrigley Field, not on the field but nearby, standing in front of a massive facility on the stadium’s southeast corner that has become an active part of the ballpark and, to hear Munson tell it, a dangerous place.

It is called the DraftKings Sportsbook, and it was a very strange place to find this journalist and attorney because he is among the most passionate anti-gambling voices in this increasingly wagering country.

“I have been a lifelong fan of the Cubs, and instead of the team entering into a business deal with DraftKings I’d rather the team would spend its money on a pitcher or a power hitter,” said Munson, explaining how the Cubs and most other teams in the NBA, NHL, NCAA and other sports leagues have entered into financial partnerships with sports betting operations.

He will tell you that he has never been a gambler, but that he understands addiction and has seen its victims. He is from a time when people might make a bet with their local bartender, the guy running the newsstand, at the track. It may have been illegal but it took place in society’s shadows. “Who gets hurt?” was the attitude.

Then came horse racing, Vegas, Atlantic City, lotteries … I’ve tasted them all.

That all changed in May 2018, when the Supreme Court declared that the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, which had essentially limited sports gambling to one state, Nevada, for the preceding 25 years, was unconstitutional. That left states free to chart their own courses for sports gambling. Most took advantage, with 38 states and Washington, D.C., offering sports betting, with other states awaiting legislation that would allow for sports gambling and casinos.

“Many warn that legalized gambling will change the nature of all sporting events,” Munson said. “Now teams are partnered with large betting outfits — DraftKings and FanDuel among the most prominent — in business deals and politicians have been blinded by dreams of revenue.”

Munson has been talking about this in front of gatherings of such local organizations as the Wayfarer Foundation, The Fortnightly of Chicago women’s club, and the Montgomery Place retirement facility in Hyde Park. Earlier this month, he delivered a lively, enlightening and more than a bit alarming talk titled “The Menace of Sports Gambling” at a First Friday Club of Chicago luncheon at the Union League Club in the Loop. (This venerable series of talks featuring authors, newspaper folks, politicians and newsmakers was created by John Cusick, the retired priest from Old St. Pat’s; next up is Jahmal Cole from My Block, My Hood, My City.)

“Gambling is uncontrolled and unregulated,” Cusick told me after Munson’s talk. “We are reminded anywhere sports gambling is advertised or promoted, and you needed to be 21 to gamble. But with a cell phone in your hand and a myriad of websites from which to choose, a 9-year-old can make wagers. Imagine the addiction that soon will be in our midst and in our families.”

Even those who know Munson are impressed by the details of his long and energetic career, which include growing up in Glen Ellyn; graduating from Princeton University; working as a news reporter for the bygone Daily News; earning a law degree from the University of Chicago; practicing law and serving as president of the DuPage County Bar Association; joining the staff of The National Sports Daily, more commonly referred to simply as The National, an ambitious sports-centered newspaper, which bled money during its brief life (January 1990 to June 1991). He became a senior writer/legal analyst at Sports Illustrated and then ESPN and ESPN.com, and was a frequent guest on radio and TV.

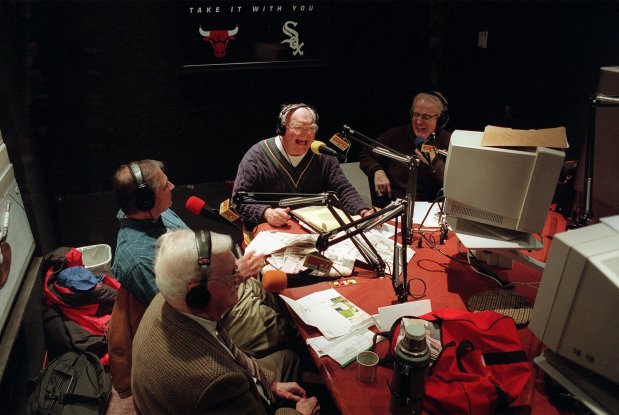

He was a semi-regular on that cigar-smoke choked “Sportswriters on TV,” which had started as a WGN radio show in 1975 before moving to television a decade later with sportswriters Bill Gleason, Bill Jauss, Rick Telander and Ben Bentley until 2000.

Munson is now a freelance writer. His beat remains the dark side of sports, “working in the shadows” covering crime, scandals, drugs, violence, money, celebrity, sex, race, gender, greed, court decisions and government actions in the sports industry.

As he is in person, his work has ever been incisive, intelligent and engaging.

He remains refreshingly frank, saying, “There is no such thing as a smart bet. … This is an industry based on addiction.” He knows about addiction, telling me that he has been “sober for 42 years.” He has never been a gambler, “Never played cards, never pulled a slot machine,” he says.

Chicago can claim one of the most infamous scandals in sports history, the Black Sox Scandal of 1919. It has been the subject of many books, such as “Eight Men Out,” which gave birth to the 1988 film of the same name. In short, it involved eight members of the White Sox being accused of throwing the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for money from a group of gamblers. were Arnold “Chick” Gandil, George “Buck” Weaver, Oscar “Happy” Felsch, Charles “Swede” Risberg, Fred McMullin, Eddie Cicotte, Claude “Lefty” Williams and, most famously, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson.”]

A Chicago grand jury indicted the players in late October 1920 and, though all were acquitted in a public trial on Aug. 2, 1921, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis the next day permanently banned all eight for life from professional baseball.

What troubles Munson most is not only the explosive growth of and accessibility of sports gambling but how it targets the most vulnerable, saying, “It is hard to escape the massive advertising campaign.” 1 trillion dollars a year.””]

“There are now 14 places to legally bet on sports across the state,” he says. “The numbers are terrifying. Everybody wants in. The focus is on the next bet and while some people can manage their betting there are many, many who become victims, part of a vicious cycle that has them chasing the money they inevitably lose, digging deeper into a financial hole.”

He was understandably rocked by the death of his wife of 55 years, Judith, in 2020. He has moved from the western suburbs into the city. He reads five newspapers a day and is in close touch with his two grown sons and their families. He tells me that Americans bet “close to $119 billion in 2023 and it’ll be around $150 billion in 2024.” Then he walked east toward his car.

Across the street, an older man was furiously pulling on one of the DraftKings’ doors. “What the hell?” he shouted. I told him the place won’t open until 3 p.m. He looked at his watch. It was 1:25 p.m. He shrugged. It was freezing outside but, “I can wait,” he said. “I can wait.”

rkogan@chicagotribune.com