The man sitting on the bar stool next to mine had spent a few minutes complaining to no one in particular about the weather and then he turned to me and, for some mystifying reason, asked, “You play pickleball?”

I do not and told him so. He pulled out his phone, hit it a few times with his fingers and said, “Just listen to this: Pickleball is a big deal. It’s been the fastest-growing sport in the country for the third year in a row.”

I nodded and let my mind drift to what I knew of Chicago being home to a company that greatly influenced the social-entertainment-sporting scenes in an earlier time. I know this because more than 30 years ago, I wrote a book called “Brunswick: The Story of an American Company.”

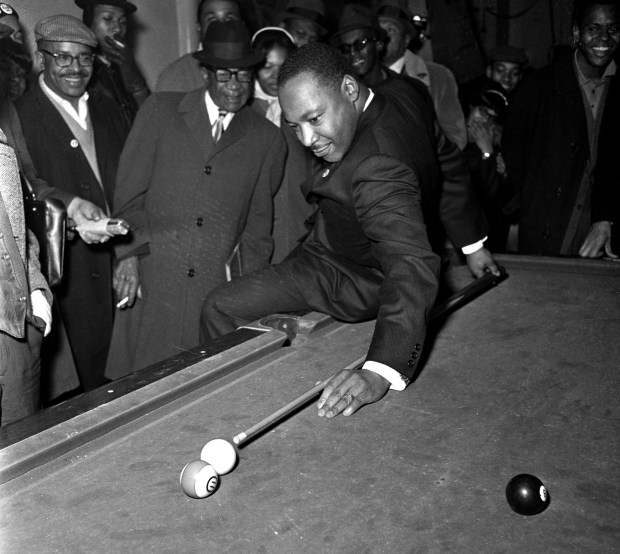

Founded in Cincinnati in 1845, and quickly making Chicago its home, Brunswick is still here, a multinational company making many things. But its first major product was a billiard table.

It was crafted by its immigrant founder, John Brunswick, becoming part of a game so popular that by the 1920s there were more than 42,000 pool halls (billiard parlors, to those of you with delicate sensibilities) in the country. Many were massive rooms, such as Detroit’s Recreation, with 142 tables, and our W.P. Mussey in the Loop with 88.

Popularity slowly declined until that great 1961 movie “The Hustler” (based on an equally great novel) created a boom and new pool halls built at that time were called “family billiard centers.” Families may have sampled them for a time but they didn’t stay. Another boom came in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Remember Muddler’s on Clybourn or Lucky’s on Institute Place?

But that, and this current pickleball mania, pales in comparison to bowling’s boom.

Yes, bowling, and tell me you have never bowled.

Bowling was popular in Colonial America, played outdoors, known as nine-pin bowl or skittles and was immediately condemned by Puritans, who believed it promoted gambling and laziness. It was banned in some of the 13 colonies before some shrewd Connecticut settlers added a pin, called this “new” game 10-pin bowling and successfully argued with authorities that it fell outside any prohibitory ordinances.

With the growth of cities, bowling moved indoors. Restaurant and tavern owners realized they could attract customers by offering the amusement, and built lanes in basements or any sliver of available space. In 1840 a British visitor observed, “of all species of (participant) sports, bowling was the national one in America.”

Moses Bensinger, John Brunswick’s son-in-law, eventually ran the Brunswick company, as his family would for decades. It expanded into the recording business, the manufacture of photographs and all manner of other things, as well as bowling innovations.

He was bowling’s primary booster, culminating in 1895 when, after hours of debate with other businessmen, he orchestrated the formation of the American Bowling Congress and the sport grew in every conceivable way.

But even so, into the 1940s it was saddled with a lousy reputation, addressed in the New York Times like this: “Before World War II, many bowling places had reputations as hangouts for rugged characters who kept the air above the lanes blue with tobacco smoke and rough language; too many pin boys sassing or heckled the ladies.”

But Brunswick and the rival company AMF were racing to develop and market a machine that would set the pins and by the 1950s these “pinsetters” began to appear and reshaped not only the sports but the landscape. And forced a lot of kids and some adults who worked as pin boys into new careers. (The late columnist Mike Royko set pins as a youth.)

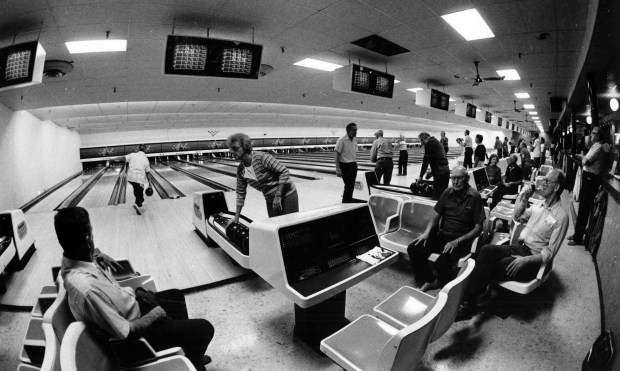

I wrote, as bowling centers started dotting the suburbs, “Bowling was fun, healthy, inexpensive and, to most Americans, novel. Even a beginner could feel the rush of a strike, a brush with perfection. On a subtler level, the centers provided social focal points for sprawling suburban developments.”

These places were lavish and huge. They had names such as Bowleteria, Bowlero, Bowlerama, Bowlodrome. Such baseball stars as Stan Musial and Mickey Mantle opened centers in St. Louis and Dallas, respectively.

These new and elegant centers dotted the suburbs. They were air-conditioned, with as many as 100 lanes. Many had built-in restaurants, cocktail lounges, snack bars and soda fountains. The more lavish offered swimming pools, meeting halls and nurseries.

Here’s a financial look at the boom: In 1954, Brunswick had $33 million in sales, with profits of $700,000; in 1961, those figures were $422 million and $45 million, respectively.

There were more than 100 magazines and newspapers devoted to the sport. Nearly 140 daily newspapers carried regular bowling columns. Most every major metropolitan area had its own local TV bowling programs.

The Tribune had a number of writers covering bowling with regularity, including the late Edward “Jim” Fitzgerald, who retired in 1992 and died in 1999.

These writers had a lot of work, the explosive growth enabled the company to go on a buying spree, purchasing such other recreational companies as Mercury, still part of today’s company.

But by 1963 the boom was over. The market became saturated. Some centers hung on by offering such innovations as “cosmic bowling,” which added loud music, dim lights and even fog machines to the mix, and offering innovations such as bumper bowling and computerized scoring.

I know a few men who stopped bowling and billiards because, as one put it, “no smoking … no bowling, no pool,” but I have visited some pretty nice bowling alleys and pool halls, filled with people. They are easy to find.

I ordered another drink and listened to the guy next to me talk about pickleball with the female bartender. I was curious if he knew how many pickleball players there were in the U.S. But I decided to wait and let him enjoy his boom.

rkogan@chicagotribune.com