The Housing Authority of Cook County is facing a potential multimillion-dollar funding shortfall that could have broad repercussions throughout the real estate market as the struggling agency looks to cut costs, possibly leading to greater expenses for its housing voucher holders and a decline in the number of the people it serves.

The agency attributes the shortfall to an increase in its voucher usage rate and rising rents, which eat into its limited dollars allocated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

As of May 1, HACC stopped issuing new housing vouchers through its primary rental assistance program, lowered the value of the subsidy, limited rent increases and reverted to 2024 payment standards for allowable rent costs by ZIP code.

Between February and May, HACC’s shortfall estimate, per a HUD tool, ranged from $3.9 million to $7 million; the estimate changes monthly, HACC said. The county agency has a roughly $22 million annual budget and is the second largest of the 99 authorities statewide, behind the Chicago Housing Authority.

“We are hopeful that (the shortfall projection) will continue to go down as we implement the cost-saving strategies,” HACC Executive Director Danita Childers said in an interview with the Tribune. “If we have less funding (from HUD), then obviously that will impact the number of families we can serve.”

HACC serves as a local harbinger for public housing authorities across the country, foreshadowing some of what could happen if President Donald Trump’s budget proposal for the 2026 fiscal year is realized or the Republican-controlled Congress approves its own cuts to HUD’s budget. Trump is proposing a roughly 43% budget slash to HUD programs, as well as a shake-up in the funding structures of the programs. In his first term, Trump also proposed sweeping cuts to HUD, but did not achieve them.

The vast majority of vouchers come through HUD’s Housing Choice Voucher Program and are doled out to local public housing authorities. Also known as Section 8, the nation’s primary subsidized housing program allows housing authorities to provide subsidies to low-income residents to find housing in the private market. Voucher holders typically pay about 30% of their income toward rent, with housing authorities covering the rest.

While Congress passed a continuing resolution in March for the remainder of the fiscal year 2025 budget that increased some areas of HUD funding — including a more than 10% boost to the Housing Choice Voucher program, according to the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials — a March news release from Senate Democrats on the appropriations committee states that the budget resolution fails to adequately finance rental assistance programs. The minority caucus said the budget will leave HUD with a $700 million shortfall and more than 32,000 fewer vouchers.

The multibillion-dollar primary voucher program helps more than 99,000 households in Illinois and more than 2 million households nationwide at a time when housing, particularly affordable housing, is scarce in Illinois and across the country. It can take years, sometimes decades, to get off the waitlist for a housing voucher.

HACC last opened its waitlist in 2020 for two weeks and received 60,000 applications. Ten thousand families were placed on the waitlist after a randomized lottery selection. As of May 5, more than 8,300 families remain on the waitlist.

The county agency manages over 1,800 units and serves more than 30,000 people in suburban Cook County. It was flagged by HUD as “troubled” in 2023 in part because of an absentee board, low-grade property inspections, incorrect reporting on leases, high outstanding balances for tenants behind on rent and failure to submit financial reports on time.

HUD declined a Tribune interview request and instead provided a statement in response to a list of questions. HUD spokesperson Kasey Lovett said HACC has a “history of funding misuse,” citing the Tribune’s previous reporting on the agency’s trips to Six Flags. She also said the idea that public housing authorities will be able to serve fewer people because of Trump administration cuts is “fundamentally flawed” and that agencies have been dealing with shortfalls “for the past few years due to rapidly rising inflation (and) poor fiscal decisions of the previous administration.”

“The President’s budget requires states and localities to have more skin in the game,” Lovett said, echoing HUD Secretary Scott Turner’s statement following the release of Trump’s budget proposal last week. “Federal funding should not be a lifeline but rather part of a comprehensive solution to address housing needs.”

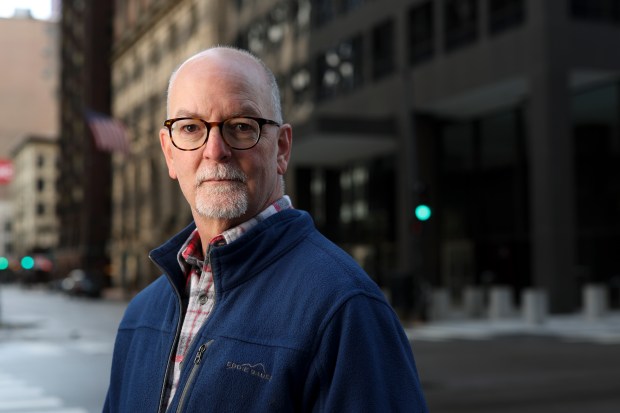

Jim Cunningham, who oversaw HUD’s entire Midwest region from the agency’s Chicago office until March, said housing authorities are not funded to the level that they need to function, which causes a cycle of shortfalls. But, he said, the Trump administration’s moves are harsher than prior administrations.

“That has been a problem in every administration,” Cunningham said, who worked at HUD for nearly 34 years. “So when you go to the extreme, it is going to be that much more difficult to serve the populations we are intended to serve.”

Cost-cutting measures

Budget shortfalls are nothing new to the Housing Authority of Cook County. The agency faced funding challenges most recently in 2017 and implemented cost-cutting measures similar to the ones it is taking now, partially due to expected HUD cuts during Trump’s first term, according to board meeting minutes from 2017. HACC projected a $1.4 million shortfall, the minutes said, for the fiscal year beginning in 2017.

Sheryl Seiling, HACC’s director of rent assistance, said at an April board meeting that these shortfalls also are tied to receiving insufficient funds from HUD.

The cost-cutting measures, HACC said, are implemented with the aim of preventing the loss of assistance to anyone currently in the voucher program. The agency has about 12,260 Housing Choice Vouchers in use with roughly 430 more available as funding allows, according to Tribune calculations based on HUD data from December 2024.

HACC will lower the value of the subsidy by requiring two people per bedroom. That means voucher holders in larger units as of May 1 will either have to cover the difference in cost between their subsidy and the number of bedrooms or move.

Childers said the agency could not estimate how many program participants could be affected by higher rent costs.

HACC also aims to limit rent increases and will deny them if they are above the permitted payment standards. The payment standards, which are based on HUD’s evaluation of area rent costs, reverted back to 2024 levels. The goal is to permit more modest rent increases to help landlords with their costs, Seiling said, while also hopefully preventing families from having to move.

When tenants do have to move, they may not be allowed to lease a higher-cost unit. Voucher recipients already often struggle and fail to find housing for numerous reasons, including because they face higher rent costs than are covered by the subsidy. Childers said she is concerned about moving challenges for program participants. The agency had a staff member who assisted with finding units for voucher recipients, Childers said, but the role is vacant.

Voucher recipients outside of HACC’s jurisdiction could also be more limited in where they can move, as they will no longer be allowed to transition their voucher from another housing authority to Cook County if they find an apartment in the area.

Agencies have to walk a “fine line” between budget and voucher usage rates, Childers said, and HUD had wanted HACC to up its use of its vouchers. A few months after HACC hit a record high for the use of vouchers in its primary program, around 94%, in August 2024 and saw 99% of its budget for the program used, Childers said the agency was projected to go into shortfall.

It took the agency five years to revert back to its standard procedures and build up its reserves following its 2017 budget woes, Seiling said at a recent board meeting. The housing authority will follow the same logic now, she said, with the reserves serving as the fallback if HUD dollars end up on Congress’ chopping block. In recent fiscal years under President Joe Biden’s administration, HACC also received funds from HUD to cover certain budget shortfalls due to lower rent collections from tenants during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Asked if the agency could have avoided some of these cost-saving measures, Childers said, “Hindsight is always 20/20.”

She said the agency has been “fairly accommodating” when it comes to landlords asking for rent increases and voucher holders asking for larger units, which has led to higher rents and, in turn, higher budget utilization. But, Childers said, the agency takes pride in that its families are located throughout suburban Cook County.

“We’re happy to be able to provide housing for lower-income families in some of the more expensive or opportunity areas so families can take advantage of better schools or access to employment,” Childers said. “That is a goal.”

Exceptions to the cost-saving measures will be made for HACC residents who are in the Emergency Housing Voucher Program, Childers said, a COVID-19-era initiative seeing its funding dry up and no additional resources coming down the pike. Once HACC’s funding runs out for its 302 emergency vouchers, at the end of 2026, those subsidy holders will transition to the primary voucher program.

The Chicago Housing Authority expects its dollars to run out for its 1,058 active emergency housing voucher holders at the end of September, said CHA spokesperson Matthew Aguilar, and will also transition those subsidy holders to its primary housing voucher program. As of January, CHA suspended pulling people for its Housing Choice Voucher waitlist until it can, Aguilar said, “absorb as many EHV’s as possible before our funding runs out.”

Concerns for the future

HACC’s budget predicament and further reductions in HUD dollars will have trickle-down effects on voucher holders, landlords and the broader economy.

Depending on the magnitude of any cuts, housing agencies will have to make “tough choices,” said Sonya Acosta, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“People on the waitlist would have to keep waiting and most of them have been waiting for years already, potentially experiencing homelessness or in difficult living situations,” Acosta said. “Congress should not entertain the idea of cuts for these programs; they are life-changing for people.”

Housing providers who spoke with the Tribune worry that HACC’s steps and further cuts to HUD’s budget could destabilize the real estate market and cause more landlords to balk at accepting vouchers. Developers rely on housing subsidies to be able to offer affordable units and maintain their properties, and their construction costs will likely keep going up with inflation and tariffs even if the subsidies don’t. Property owners fear they might not get paid or paid sufficiently through the voucher program.

“When you have a housing authority that is struggling to meet the subsidy needs for thousands of individuals and families and cannot meet what that market bears and places … more of a burden on the residents and families, that is adverse to the broader economy of this region,” said Charlton Hamer, senior vice president of Habitat Affordable Group, the affordable housing arm of Chicago-based real estate firm the Habitat Co.

Hamer’s company has worked with public housing authorities across the country and has about 3,000 subsidized housing units in Cook County, including through the primary voucher program.

As for HACC’s budget restriction efforts, Hamer said, “I don’t think there is anything else they could have done right now.”

Childers said she has heard complaints from both voucher holders and landlords about the agency’s cost-saving measures, saying she knows “nobody wants to move” and that landlords have businesses to run.

“It is a difficult situation,” she said.

Mark Gillett, president of the Public Housing Authorities Directors Association and executive director of the Oklahoma City Housing Authority, said HACC is “not in a unique situation.” A majority of public housing authorities nationwide were in shortfall by the end of 2024, he said, and their first steps to mitigate costs will be to stop issuing new vouchers. Next steps may include paying a smaller percentage of the tenant’s rent.

Gillett, who participated in a March conversation with members of Congress in the HUD appropriations subcommittee to discuss the “funding crisis,” said it was clear that Congress is “not too willing to provide more money.” It is unclear how public housing authorities will continue to serve their populations if no additional money is available and rents continue to go up.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Gillett said. “We have got to get some unique ways to run our programs.”