A century ago, Henry Gerber founded America’s first documented gay rights organization in a boardinghouse at 1710 N. Crilly Court in Chicago.

It was once part of a complex of townhouses built for well-heeled newlyweds. Today it sits amid Old Town’s mix of high-rise condos and renovated brownstones.

A plaque in the sidewalk outside the building where he lived on the second floor notes it is a Chicago landmark, explaining that the home was where Gerber wrote at least the first of the two published issues of “Friendship and Freedom,” the first documented gay periodical in America.

But in his day, Gerber’s neighbors were society’s outcasts. Prostitutes worked in rooms on either wing of Crilly Court. Being off the beaten path was fine with him. He didn’t want his address to be generally known.

Gerber didn’t hold meetings of the Society for Human Rights in his rented room. He and his handful of followers gathered in the basement of the Crilly Court building. It had direct exits to the outside. Gays could come and go without running a gauntlet of neighbors’ eyes. Even so, many were reluctant to attend.

“One of our greatest handicaps was the knowledge that homosexuals don’t organize,” Gerber wrote in 1962. “Being thoroughly cowed, they seldom get together.”

Gays were despised for simply being different, and that hostility was written into law. Homosexuals faced being committed to a mental asylum or jail time.

Gerber explained the objective of his gay rights organization was to “promote and protect the interests of people who by reason of mental or physical abnormalities are abused and hindered in the legal pursuit of happiness, which is guaranteed by the Declaration of Independence, and to combat the public prejudices against them by distributing the factors according to modern science among intellectuals of mature age.”

In fact, American psychiatry considered homosexuality a mental disorder for decades thereafter. Gerber’s optimism was acquired at one of the stopping places on the bumpy road to acceptance of his sexuality.

Born in Germany, Gerber immigrated to the United States in 1913. “I had no idea that I was a homosexual,” Gerber later said.

He had limited sexual experience as a boy and subsequently more complex encounters in Chicago. He and his sister settled there, following the lead of a family friend. Gerber found his way to Washington Square Park, a meeting place for gays adjacent to the Newberry Library.

Gerber was at some point committed to an insane asylum because of his homosexuality. Released after a year, but fearing another incarceration, he volunteered for military service. He was assigned to an Army unit occupying Germany after its defeat in World War I.

On leave, Gerber went to Berlin where attitudes toward homosexuality were relatively liberal and, as Gerber’s biographer Jim Elledge wrote, “Das Lilia Liede,” was heard in myriad hot spots. “The Lavender Song,” the first gay anthem, was also available as a phonograph record. Erotic magazines were displayed on newsstands that the police would have confiscated in the United States.

Berlin was also the site of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Profoundly affected by the 1895 trial of Oscar Wilde, a gay English dramatist, Hirschfeld began to specialize in human sexuality. Gay himself, he campaigned for the legalization of homosexuality.

“Please tell the public everything about us,” a gay man pressured to marry wrote to Hirschfeld just before committing suicide.

Reflecting on what he experienced in Germany, Gerber wrote: “I had always bitterly felt the injustice with which my own American society accused the homosexual of ‘immoral acts.’ What could be done about it, I thought.”

Discharged from the Army in 1923, he returned to Chicago determined to form a gay rights organization like Hirschfeld’s. Getting it incorporated was problematic. The legal papers required a statement of purpose, and its purpose collided head-on with homosexuality’s illegality.

On the advice of a liberal-minded lawyer, the application included the clause: “The Society stands only for law and order,” its officers swore, “and does in no manner recommend any acts in violation of present laws nor advocate any matter inimical to the public welfare.”

One of the initial issues was whether the society should be a purely homosexual organization and “exclude the much larger circle of bisexuals?” Elledge, Gerber’s biographer, wrote in “An Angel in Sodom.”

But the issue of bisexuals, who often had a traditional wife and family while secretly living a gay life, and how they might endanger the organization presented itself not too long after Gerber founded his organization.

On July 11, 1925, he heard a loud pounding on the door of the apartment at 34 E. Oak St., where he had moved from Crilly Court.

“Where’s the boy?” a detective shouted when Gerber opened the door. He was alone. The detective was accompanied by a couple of uniformed officers and a reporter from the Chicago American, a Hearst newspaper. The officers found the organization’s files and arrested Gerber.

The following day’s headline in the paper announced: “Girl Reveals Strange Cult Run By Dad.”

The accompanying story identified the girl as the 12-year-old daughter of Al Meininger, president of the Society for Human Rights. She reportedly had asked an officer at the Chicago Avenue police station, “why her father carried on so.” Men visited afternoon and night, and engaged in “strange rites.”

Police were sent to the Meininger apartment at 532 N. Dearborn St. Pushing through the door, they arrested Meininger. The Chicago American’s story might have been hyped up, as Hearst-owned papers were known to cross the line between fact and fiction.

Meininger’s wife had complained to a social worker about his homosexual activities. Meininger and Gerber met in the police station’s cells. Gerber was furious at hearing that the social worker was going to include him in her testimony.

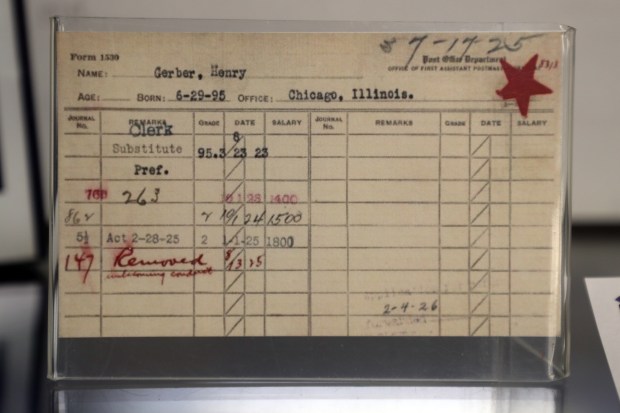

The newspaper article got him fired from his job as a postal worker. Meininger’s indiscretion also brought down Gerber’s gay rights organization. Gerber refused to speak to Meininger.

After paying a $10 fine for disorderly conduct, Gerber left Chicago for New York. Intermittently he resumed his activism. But in a 1945 letter to a veteran of his movement, Gerber wrote: It is “your and my misfortune to have been born 1,000 years too soon or 1,000 years too late.”

At 52, Gerber reenlisted in the Army hoping to get increased retirement benefits. He spent the remainder of his years in the U.S. Soldiers Home in Washington, D.C.

On New Year’s Eve of 1972, Gerber died at age 80 in the home’s hospital and was buried in the cemetery there. His passing went unnoted in the gay rights community.

Except perhaps by a member of the staff of One Magazine, to which Gerber subscribed.

His letter to Gerber was returned to him by the Soldiers Home. Its envelope was stamped “DECEASED.”