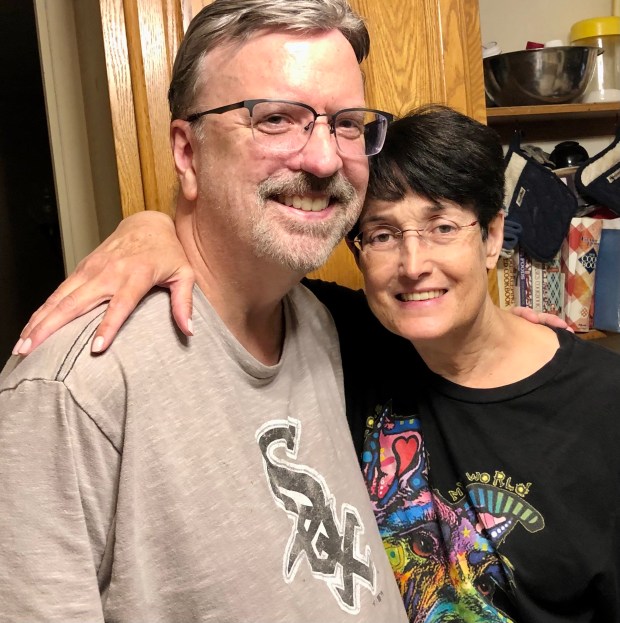

Phil Allen’s 25th anniversary present to his wife, Meghan, will be hard to top — he gave her one of his kidneys.

“It was a happy coincidence that it happened on our wedding anniversary,” Phil said. “It made it easy for me not to buy her an anniversary present.”

“We didn’t plan it that way,” Meghan added. “That’s when both of our preferred surgeons were available.

“It was destined to be. That made it more special. … When your husband gives you a kidney on your 25th wedding anniversary, what kind of gift could you possibly give back?”

Phil said it was a “no-brainer” for him to be a living donor.

“She needed a kidney and I’m her husband,” he said. “If she wasn’t a match, there was a chance I could still do it because of the donation chain. … I was a perfect match for her, so we didn’t have to do that.”

Meghan, an inventory analyst, said a blood pressure issue damaged her kidney. Last spring, her kidney function was at 35% but by midsummer it was down to 20% and then 14%. At that point, she would have gone on the transplant list, where patients can linger for five years or more.

She was told by her medical team at University of Chicago Medicine about the possibility of living organ donation. Having a living donor meant not adding her name to a list and not doing dialysis, along with the prospect of a better longterm outlook.

“If you get a deceased donor kidney, it’s got a lot of mileage on it,” she said. “That may only last for four or five years.”

Phil had extensive testing, mainly over one day. “It was a long day. It went from 7 in the morning until 6 at night. … It was the most thorough physical I ever had.” In addition to physical testing, he spoke with a counselor about the possible outcomes and to make sure he wasn’t being pressured.

Luckily, their recovery was fairly rapid, with Meghan, adding that she feels “fantastic” now, and they heartily recommend other kidney patients try this donation method.

“I would say if you’re in good health and cleared by your doctor, by all means do it,” said Phil, who works in the marketing department for a benefits management company. “I’ve gone back to my life 100%. I don’t even miss the kidney right now. I don’t notice it’s gone.”

Because their surgeries were done laparoscopically, scarring is minimal, especially for Phil, who said his incision was only 4 or 5 inches long. “For me, it’s a little bigger,” Meghan said. “You look like Frankenstein with all the staples.”

The living organ donation process was a little more complicated for Markham resident Gelila Tekeste, who gave a kidney to Mike Haddon, her husband of 17 years. After a cyst was discovered on one of her ovaries during the evaluation, she had surgery to remove her ovaries and fallopian tubes and faced a few months of recovery before the transplant surgery December 26.

She said a higher power was involved in her donation. “Honestly, I would say it was God’s work. It wasn’t me,” said Gelila, an application developer for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. “I am really terrified about needles, and they can never find my veins. Every time I do lab work I’m stressed about it for a few days before the appointment.”

She said her mother had been praying about a kidney donor but didn’t realize it would end up being her daughter. “It took her a couple of days, but she called me and said ‘I had a revelation, and what you’re doing is a good thing. I approve of it.’”

Her husband, a signal maintainer for Metra, was reluctant for his wife to have the surgery because of their two teenage children, but Gelila’s thinking was different.

“We have two kidneys and we can live fine with one kidney. Why not give one? It’s a surgery that has been done many times successfully in the United States,” she said. “And he’s my husband. He’s an amazing person and amazing husband and amazing dad. Of course we’re going to share our lives and help each other as much as we can.”

Mike is appreciative of his wife’s gift. “It means everything. I’ve always said from the time I met her that she was my guardian angel.”

Before his diagnosis, Mike had noticed no symptoms of kidney disease. He’d gotten routine blood work during a checkup, and his doctor called him wanting to go to the hospital as fast as possible because his numbers were so far out of the normal range.

While on medication to treat his condition, his kidney function went from 20% to 3% functionality within six months and he began receiving peritoneal dialysis at home.

“Came to find out I should never have done that because it was worse for me than going to the center. The numbers keep going down, trying to increase fluid in my body,” Mike said. “The process was extremely long and was every day, eight and nine and a half hours a day and you have to be in bed.”

Gelila said preparation and support are important for being an organ donor. “I would say be prepared mentally and physically, but once you know you’ll be able to donate a kidney, go ahead and do it. It’s a beautiful thing. It feels really good. But at the same time I would say make sure you have family and friends who will help you throughout your recovery. The first few weeks you won’t have any energy to do anything.”

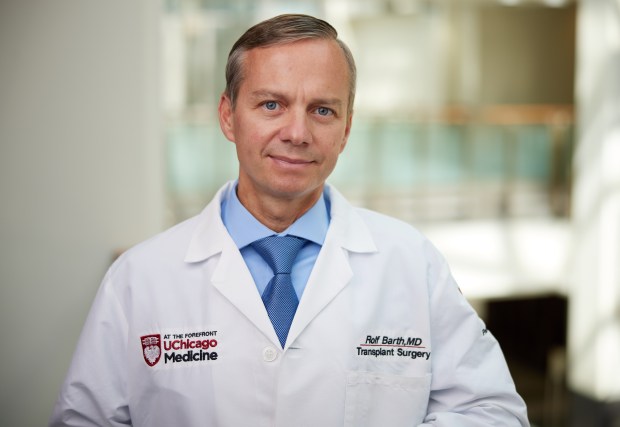

Someone who knows a lot about the benefits of living donors is Dr. Rolf Barth, co-director of the UCHicago Medicine Transplant Institute and director of the kidney program, a job he’s held since 2020 after practicing in an East Coast transplant program for 14 years. He pioneered minimally invasive surgery for living kidney donation and performed the first scarless single-port laparoscopic donor nephrectomies (kidney removal) and has gone on to do about 1,000 of the procedures. He used that method to extract Gelila’s kidney and was the surgeon to transplant Meghan’s kidney.

“I offer it to all my patients,” he said. “A donor doesn’t necessarily care if they have a big scar or a small scar. It doesn’t make them any healthier or smarter or stronger, so if we can do the surgery with a little better technique and cosmetics, I feel confident offering them a more surgical approach.”

Kidneys are the most common organ to be transplanted, and that need is great, Barth said, adding that 600,000 people in the United States are on dialysis and only 100,000 of those go on the transplant list. About one-quarter of donors are living donors, but he’d like to see that number grow because of its many advantages.

Patients with living donors can be transplanted before they begin dialysis instead of waiting for five or seven years and having to suffer the treatment. Also, outcomes are better. “The success of living donors, kidney transplantation can be close to 99% after one year. You’re having a complex surgery that has nearly a 100% success rate. That’s just amazing,” Barth said, adding that although the success rate for deceased organs is 91 or 92%.

A final reason is the lifespan of a kidney, especially for younger patients. “The expected survival of a deceased donor kidney is close to seven years.” Living donor kidneys, on the other hand, can last 20 to 30 years. “A deceased kidney, especially for a younger person, may mean they need more than one transplant,” he explained.

Potential donors “get a million-dollar workout,” he said, “and if they’re not going to live a normal life with one kidney, we don’t let them donate. There’s no twisting of arms making people donate, people who aren’t ready,” he said. “We have independent living donor advocates who aren’t affiliated with the program to make sure there’s no coercion or financial risks to people. We’re incredibly cautious as a field about that.”

As a university-related hospital, UChicago Medicine sometimes gets living donors who “just hear the story and get inspired because they want to help,” Barth said. Anyone interested can fill out a questionnaire on the hospital’s website or call. Basic blood work to determine if their kidney function is good follows, and those who have been reviewed have their kidneys scanned in 3D.

Donors incur no costs for the testing because recipients’ insurance pays for it, and lots of national programs exist to provide extra assistance such as lost wages for donors, he said.

“The whole field of transplantation is based on the generosity of organ donors. Some of them are deceased donors and their last charitable act after they’ve passed away is to give an organ, “Barth said. “Living donors are still living so they have the personal reward of donating a piece of themselves that saves a life.”

Melinda Moore is a freelance reporter for the Daily Southtown.