Within a few years Chicago’s Board of Education will be fully elected.

For now, though, Mayor Brandon Johnson appoints the city’s school board, which in theory should mean he is the decision-maker on important doings at Chicago Public Schools.

Yet Johnson learned last week that on the budget at least, it’s schools CEO Pedro Martinez and his board — and not City Hall — that are calling the shots. Martinez evidently has backing of the school board, every member a Johnson appointee, so much so that he rejected the mayor’s directives, independently drew up a budget that ignores some of Johnson’s priorities, and seems prepared to approve it at a meeting next week.

The set-to came into public view after Johnson suggested the board should obtain a long-term, high-interest loan in order to address a $500 million budget gap at CPS — and reduce the need for layoffs of staff.

The board astutely ignored the mayor’s advice. In its $9.9 billion Chicago Public Schools operating budget, released last week, a new tranche of borrowing was nowhere to be seen. The board’s fiscal plan also included staff cuts the mayor doesn’t support.

The budget is far from perfect. There is no provision for pay raises, even though negotiators are expecting a new contract to include a 4% pay hike this coming school year. There’s also a $175 million pension payment coming due.

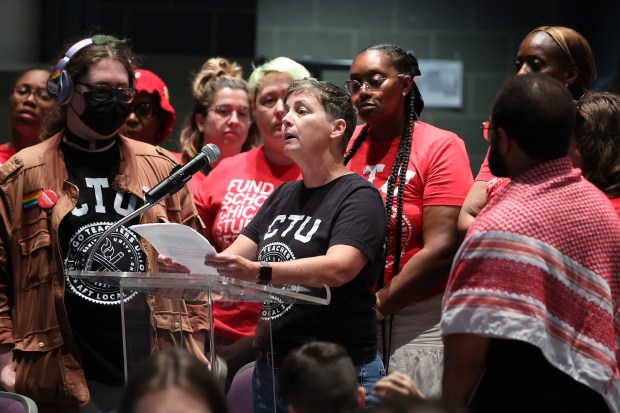

Johnson’s resistance to staff cuts got rhetorical backing when I checked in with the union where he used to work. “If you’re going to cut a bunch of essential positions at a time when we’re negotiating with you — well, bring it on,” said Jackson Potter, a vice president and lead negotiator for the CTU.

If the board passes its proposed budget next week, despite the mayor’s deep misgivings, it will be an exercise of independence rarely seen from an appointed group in Chicago. There has been plenty of talk about the potential downsides of an elected board, which starts in November, when 10 of 21 slots will be filled by voters.

Divisiveness could result. The cost of running might result in inequitable representation on the board. There is a risk that self-interested groups — such as the CTU or perhaps backers of charter schools — might put up candidates to “capture” control of the school system.

Editorial: Brandon Johnson’s desperate loan gambit to keep the Chicago Teachers Union happy

Still, a big upside came into view last week: A board acting independently can act as a check on the mayor or the schools CEO as needed, especially by exercising fiscal responsibility that some mayors may not. A little challenge and scrutiny can be to the good. Taxpayers, parents and even children are better served by a board willing to challenge the mayor or schools CEO.

When Johnson returned from a trip to Springfield this past spring without securing the school funds he sought, the board’s skepticism about his wherewithal on budget matters no doubt grew. To solve CPS’ fiscal problems, the board evidently determined it needed to set its own course.

After all, the pressures facing CPS will only grow over time. Some $300 million in pandemic-related relief funds kept the CPS shortfall at “only” about $500 million for the 2024-25 school year. Getting it right for the coming school year is important — especially with a new, likely four-year contract under negotiation.

Next year, those federal funds will stop flowing altogether — creating a larger fiscal hole that won’t be easily filled. Meanwhile, staff and the mayor’s office have provided little apparent attention to a teachers’ pension fund that has enough resources to cover only about 47% of its pension obligations — and carries an unfunded pension debt of $13.8 billion.

And payments on CPS’ $9.3 billion in long-term debt will require more than $800 million this year. Yet direct school spending continues to mushroom — rising 30% since fiscal 2019, to $4.8 billion this past school year, according to a Civic Federation report. A new approach to spending, based on school need, not student head count, is an equity-inspired shift that is accelerating the increase in costs.

No wonder the board is stepping up. It would not be fulfilling its responsibilities if it did not. When it comes to covering the cost of teaching the city’s children, the answers aren’t coming from anywhere else.

As for Johnson, it appears he’ll just need to work with an independent-minded board a few years earlier than he might have expected.

I asked Jason Lee, Johnson’s senior adviser, how a mayor who is having such trouble with a board made up of his own appointees might successfully work with the Board of Education once members are answerable to the voters and not the mayor.

“It doesn’t mean you have no influence. It means you have the influence you earn,” Lee said.

Given the events of last week, and with the first round of elections coming in November, it appears Johnson still has a lot to earn.

David Greising is president and CEO of the Better Government Association.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.