Kilgubbin won’t be found on modern-day maps of Chicago, but there once was a place known by that name — a settlement of Irish immigrants on the city’s North Side.

In the 1850s and 1860s, Kilgubbin was often mentioned in the pages of the Tribune and other Chicago newspapers. The name became symbolic of slums where poor Irish immigrants lived in ramshackle shanties, squatting on property they didn’t own. In an era when the Irish faced widespread prejudice, “Kilgubbin” was used as an insult.

Of course, Kilgubbin wasn’t the only place where Irish people lived in Chicago during the city’s early decades. In the 1830s, Irish laborers dug the Illinois & Michigan Canal, settling in a spot once called Hardscrabble, which became the South Side’s Bridgeport neighborhood. And when the Great Famine devastated Ireland in the 1840s, Chicago was a destination for thousands of Irish people fleeing starvation. By 1850, 1 out of every 5 Chicagoans was an Irish immigrant.

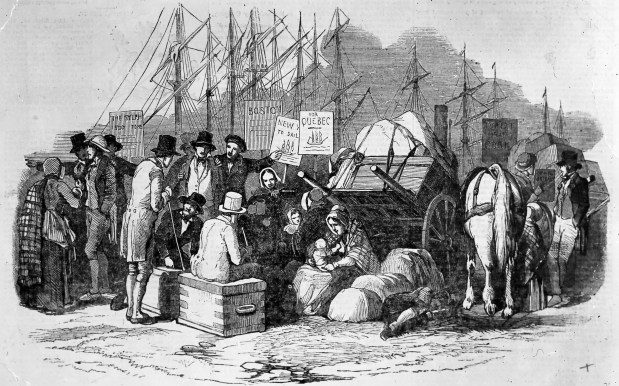

Kilgubbin’s original inhabitants came from Kilgobbin in Ireland’s County Cork, where the nobility evicted them and shipped them to America, according to a Tribune article. “They were literally ‘dumped’ at the Port of New York, with scanty clothing and absolutely penniless,” the Tribune reported. “A Western railroad contractor brought a ship-load of them to Chicago.”

They settled along the Chicago River’s north bank west of Franklin Street and south of Kinzie Street, extending west to Wolf Point and the river’s North Branch — an area where the Merchandise Mart and shiny skyscrapers stand today. “The Kilgobbinites put up such shanties as they were able,” the Tribune noted.

Other immigrants from Ireland soon followed. “They were either so indifferent or so wanting in knowledge of the value of property and of the methods of securing title that very few of them took the trouble to acquire the ownership of the ground on which their houses stood, though it could be done for a mere trifle,” the Tribune wrote.

By the 1850s, the growing Kilgubbin area included “many thousand inhabitants, of all ages and habits, besides large droves of geese, goslings, pigs and rats,” according to the Chicago Times.

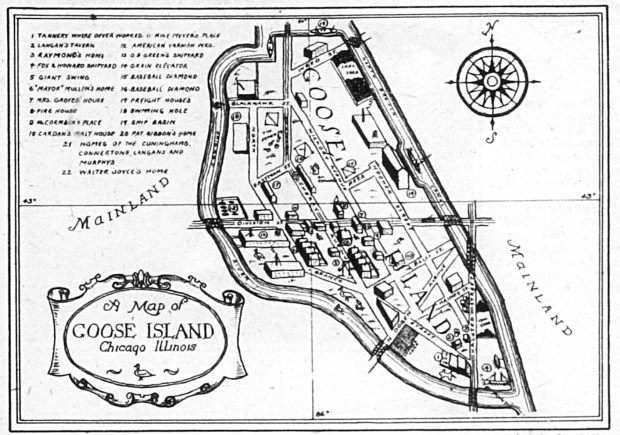

Some Kilgubbin residents kept their geese on a mound of yellow clay in the river, which was called Goose Island — not to be confused with the larger Goose Island that today’s Chicagoans are familiar with. This early patch of land with the same name was only about 20 square yards.

Cows were also common in Kilgubbin. A resident named O’Brien caused an uproar in 1859 when he accused a neighbor named Ferrick of stealing his cow. “The little O’Briens … one after another glued their eyes to the cracks in the enclosure of the Ferricks’ and tearfully hailed their long lost favorite,” the Tribune reported.

O’Brien sued Ferrick, and the cow was subpoenaed, making an appearance in the square outside the downtown courthouse. But the jurors decided the cow was Ferrick’s and ordered O’Brien to pay court costs of $118, or roughly $4,000 in today’s money — three times the cow’s value.

The same year, the Tribune described Kilgubbin as “the haunt of the vilest and lowest population of the city,” where visitors faced the danger of being “swamped in mud, suffocated with stench, or bludgeoned in wild Celtic freakishness.”

But such fears didn’t prevent politicians from seeking votes in Kilgubbin. According to neighborhood lore recounted in the Tribune, Mayor Walter Gurnee had campaigned there in the early 1850s, dancing to a fiddler’s music with a barefoot girl — an experience that prompted him to quote Irish poet John Francis Waller: “Search the world all around, from the sky to the ground, No such sight can be found as an Irish lass dancing.” As legend had it, this helped Gurnee to win the election. Chicago’s Irish weren’t yet serving as aldermen and mayors, but they were already becoming a political force to be reckoned with.

As time went on, property owners evicted Kilgubbin’s squatters. In 1863, police officers ordered many residents out of their shanties. “Mrs. O’Flaherty declared, with arms akimbo, that she would not leave for the ‘likes of yez,’ and so Mrs. O’Flaherty’s house was pulled down over her head,” the Tribune reported.

Kicked out of Kilgubbin, many of these Irish Americans moved north, settling near the river’s North Branch north of Chicago Avenue and taking their neighborhood’s name with them — this area was also called Kilgubbin.

Kilgubbin’s most famous moment came in August 1865, when Chicago Times reporter John M. Wing traipsed through the muddy enclave and the city’s other “squatter settlements,” which had a total population estimated at 15,000. “The progress of civilization, the rapid growth of the city, and the consequent increase in the value of the property, do not seem to exert much influence upon these people,” Wing commented.

According to Wing, a typical shanty in Kilgubbin contained one room occupied by a cow and a pig; a second apartment where geese and chickens roosted; and a kitchen, where 10 to 12 children were “lying upon the floor in rows, in the most squalid rags and filth.”

Wing described Irish shanty dwellers as prone to feuds and fights: “The females are extremely tenacious of their rights, and consequently, quarrel and fight among themselves, pull hair and disfigure eyes. In this respect a more turbulent race of people never existed. The women encourage their children to quarrel and fight, and teach them how it is done by actual combats with their neighbors. Every breeze blows dust into their eyes from somebody’s patch with whom they are at loggerheads, and a fierce contest with shillelaghs ensues.”

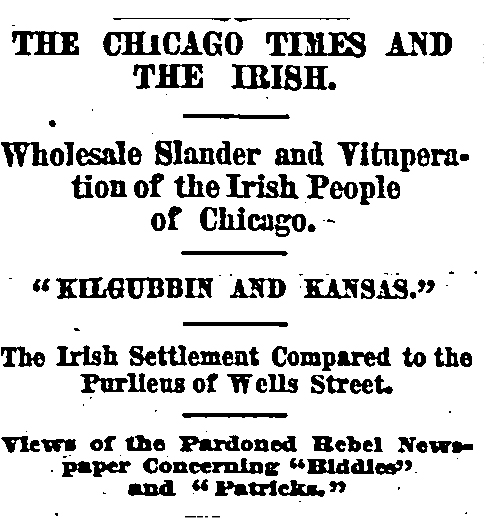

The Times, a notoriously sensational newspaper run by publisher Wilbur F. Storey, had been considered a friend of Irish immigrants. Like the Times, the Irish supported the Democratic Party. But a day after the Times published Wing’s article — without a byline — 1,000 Irish readers canceled their subscriptions.

“Irishmen rush into the office, and threaten to kill the individual who wrote it, if they can only lay hands upon him. The excitement is intense,” Wing wrote in his diary (which was published as a book in 2002).

The Tribune reprinted the entire Times article — and then published it a second time, in 1866, eagerly presenting it as evidence of the rival newspaper’s “Wholesale Slander and Vituperation of the Irish People of Chicago.”

By the late 1860s, the name “Kilgubbin” was appearing less often in newspapers, as the area came to be known by other names. It was sometimes considered a part of the North Side’s “Little Hell” area, but its most common moniker was Goose Island. This island in the river’s North Branch had been created by a canal, originally excavated to dig up clay for making bricks. (At 160 acres, it’s far bigger than the tiny Goose Island that once existed near Wolf Point and the original Kilgubbin.)

In the years after the Irish arrived, industry and railroads took over much of the island. In 1886, the Tribune reported that only 300 residents, most of them Irish, were still living there. As the century ended, Chicago’s Irish population was concentrated on the South and West sides, though a smaller community endured on the North Side. Those who stayed on Goose Island upgraded from shanties to frame cottages and two-story houses.

Looking back on the history of Kilgubbin and Goose Island, the 1886 Tribune article concluded that these places were probably never “as black as they have been painted.” And it noted that most of the “tough” characters had been “weeded out.” Describing Goose Island’s residents, the newspaper took a far more positive view of the Irish than it had just a few decades earlier.

“They are a pretty good class of people,” the Tribune said. “They are thrifty and industrious. … The great majority of the people are sober and hardworking.”

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at grossmanron34@gmail.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com.

Sign up to receive the Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter at chicagotribune.com/newsletters for more photos and stories from the Tribune’s archives.