For many Chicago viewers, retiring WGN-TV meteorologist Tom Skilling has long been an eternally sunny on-air presence, whose detailed forecasts and genuine enthusiasm somehow made upper air patterns interesting.

The cult of Skilling runs so deep, just about everybody does an overly-cheerful impression of Chicago’s longest-tenured weathercaster.

What they may miss, however, goes on behind the scenes, where Skilling is far more complex than his caricature: a diligent, almost obsessive meteorologist who spends 15 hours a day glued to computer screens, analyzing reams of data in an endless quest to accurately predict the Windy City’s capricious weather.

“You’ve been humbled enough by Mother Nature to know that you’re not going to get every one exactly right,” Skilling said. ”But you sure try. You live and die trying.”

Most of the time, Skilling got it right.

In late January 2011, for example, Skilling told viewers of a potentially “formidable” winter storm nearly a week in advance, tracking its formation every step of the way. When the Groundhog Day blizzard arrived, it dropped 21.2 inches between Jan. 31 and Feb. 2, the third biggest snowstorm in Chicago history.

“This is our storm,” Skilling announced matter-of-factly as furious snow totals piled up and paralyzed the city. “It is a doozy.”

Over the years, Skilling has delivered thousands of forecasts, from rain and lake-effect snow to the more arcane cyclonic vorticity, with expertise and a folksy warmth that has endeared him to generations of Chicagoans.

But if March comes in like a lion, for the first time in nearly half a century, Skilling will not be on the air to help viewers weather another storm. The once gee-whiz kid of Chicago meteorology, now the avuncular dean of local TV weathercasters, is retiring at the end of the month.

“In some respects, you look back on everything that’s happened and you think, my god, it seems like ages ago, and in other respects you think it’s gone by so fast,” said Skilling, who turns 72 Tuesday.

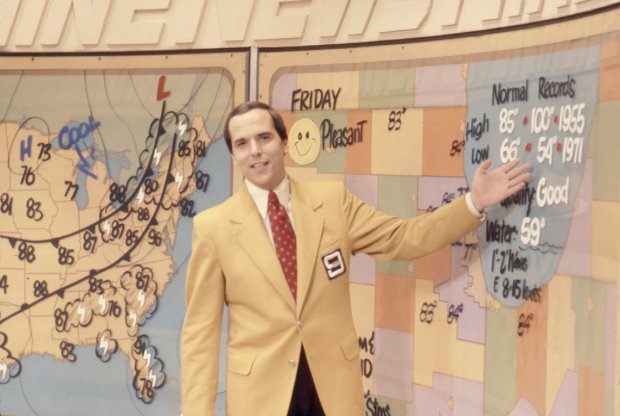

Skilling made his debut on WGN in 1978 sporting a full head of hair, a yellow Channel 9 news blazer and a remarkably buoyant disposition. On Feb. 28, he will spin out of his chair at the weather desk, make a beeline for the studio and give his final forecast during the 10 p.m. news.

WGN has named Demetrius Ivory, 48, a 10-year veteran of the station, to succeed Skilling as chief meteorologist, and competitors have some familiar faces to carry on, but the imminent sign-off of Chicago’s most iconic weathercaster will leave a void.

“We’re losing a big part of what WGN is,” said evening news anchor Micah Materre, who has worked alongside Skilling for nearly two decades. “He is the gold standard, he’s the one that made WGN so unique all these years.”

A Pittsburgh native, Skilling moved to New Jersey when he was 2 after his father, Thomas Skilling, an industrial valve salesman, took a job in New York. The oldest of four children – his brother Jeffrey would find a different kind of fame as CEO of Enron – Tom had an “inherent” interest in meteorology growing up.

Instead of spending his paper route money on baseball cards, young Skilling subscribed to a daily weather map service.

In 1965, the family moved to west suburban Aurora when Skilling’s father was transferred to the home office of Henry Pratt Co.

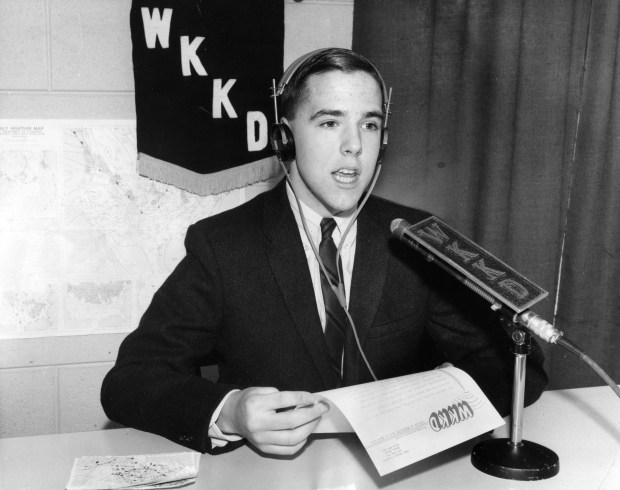

Unable to continue receiving the weather maps in a timely fashion, Skilling wrote an eight-page letter to Aurora radio station WKKD to see if they could provide him with an alternative. Intrigued, the station’s then-program director, Rusty Tym, set up a meeting with the 14-year-old Skilling.

“I told them, if they can get me some weather maps, I had the audacity to suggest that I’d do a better forecast for Aurora than they were getting from Chicago,” Skilling said.

The pair visited the National Weather Service office in Chicago and somehow convinced the staff to print an extra weather map each day and mail it to Skilling.

After getting his radio operator’s permit at the FCC office in Chicago, the weather wunderkind was soon delivering forecasts on WKKD – while still attending West Aurora High School.

“That started my broadcast career,” Skilling said. “Every day before I went to high school, I’d go down to the post office in Aurora, pick up these envelopes with the weather maps in them and I’d do a broadcast in the morning and update it in the afternoon using a newspaper weather page.”

Skilling added TV to his high school resume at 17, doing evening weather reports for the fledgling WLXT-Ch. 60, an Aurora UHF station that went on the air in 1969.

Working with his younger brother Jeff, the pair painted a map and put a plexiglass board on it. The future Enron CEO handled the control room, while Tom delivered after-school TV weathercasts for viewers that somehow stumbled upon the high-frequency, low-budget station.

“The operation was modest, to say the least,” Skilling recalled. “But what an experience.”

In 1970, Skilling attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where he studied meteorology and journalism while doing the weather for local radio and TV stations.

His first job out of college was at WTLV-TV in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1975. But Skilling soon returned to the Midwest at WITI-TV in Milwaukee, where he was paired with the station’s longtime weather sidekick, a wisecracking puppet named Albert the Alley Cat.

Skilling and Albert were a hit on Milwaukee TV, but on Aug. 13, 1978, the eager 26-year-old meteorologist returned to Chicago for a new gig at WGN – sans the puppet. Nearly 46 years later, Skilling’s solo act has become a Chicago broadcasting institution.

Cracking into the Chicago market, Skilling was welcomed into the TV weathercasting fraternity he had idolized growing up, notably by Harry Volkman and John Coleman.

Skilling first visited Volkman in the mid-1960s at the Merchandise Mart with his parents, where the popular WMAQ-Ch. 5 meteorologist, known for adding a “whoosh” sound effect to windy forecasts, made the Aurora teen a weather observer.

Volkman remained a friend and mentor to Skilling, even as they became on-air competitors. Skilling spoke at Volkman’s 2015 memorial service.

Coleman, a fixture on WLS-Ch.7 news during its “happy talk” heyday in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, best known for his colorful personality and booming voice, also took Skilling under his wing.

Skilling said he and Coleman met regularly for dinner after their respective 10 p.m. weathercasts.

Coleman went on to co-found The Weather Channel in 1982, where he tried unsuccessfully to lure Skilling to leave WGN and Chicago to go nationwide.

“He offered me a job when my first contract was up to go work at The Weather Channel,” Skilling said. “I didn’t want to go to Atlanta. I like the changing seasons up here. And I like doing my own work, my own analysis, my maps and all the rest.”

While he turned down the job, Skilling cut the first demo tape for Coleman to show ad executives what The Weather Channel would look like.

Skilling diverged from his late mentor in another significant way, when Coleman became a controversial and prominent climate change denier.

After a half century of meteorological study, and firsthand experience between second homes in Hawaii and Alaska, Skilling is convinced that climate change is an undeniably real danger.

He cited the increased frequency of destructive weather events such as major storms, heat waves and droughts as evidence of “profound” man-made climate change.

“The speed at which it’s occurring is what’s dramatic,” Skilling said. “Climate is changing 10 times faster than at any point in 300,000 years or so that humans are believed to have walked the planet.”

The only time the amiable Skilling loses his cool is when his weather computer crashes on deadline or he encounters a climate change denier, according to colleagues.

Skilling starts scanning the weather every morning from a home office in his Edgewater apartment overlooking the lake. By mid-afternoon, he heads over to the weather center at WGN studios on West Bradley Place to prepare his evening forecasts.

His long workdays often extend well past the 10 p.m. newscast.

“He is the real deal, almost to a fault,” former WGN news anchor Mark Suppelsa said. “Management had to say, ‘Tom go home, it’s 11 o’clock at night, you need to get some rest.’”

Skilling draws data from up to 32 models each day, “ensembling” the results to come up with the most accurate forecasts possible. He avoids sensationalizing the weather with extreme predictions, but when big storms loom, tries to provide early warning.

Over the years, Skilling has covered every major weather event to hit the Chicago area, from the 1990 Plainfield tornado to the 1995 heat wave to the Groundhog Day blizzard of 2011. He still gets emotional about the damage they caused, especially when forecasters fell short.

In August 1990, a rare and powerful F5 tornado cut a 16-mile path of destruction through southwest suburban Plainfield and Crest Hill, killing 29 people and injuring 350.

The devastating tornado came without any warning from the National Weather Service, which lacked the equipment to detect the most powerful late-season twister to ever hit Illinois.

“They never put it out,” Skilling said. “All of us in the profession, we were so saddened by that. The system broke down. They had a severe thunderstorm watch out that day, instead of a tornado watch.”

The National Weather Service accelerated the planned installation of a Doppler radar station in nearby Romeoville the following year to help identify tornadoes more quickly.

Skilling said that forecasting is “light years ahead” of where it was when he started his career, with models that give meteorologists “more than a fighting chance” to stay ahead of the weather.

Getting it right remains a daily obsession for Skilling.

“There is nobody who is more distressed by a busted forecast than somebody who’s doing the forecasting,” Skilling said.

In addition to his on-air duties, Skilling produced the Chicago Tribune weather page from 1997 to 2022. The partnership survived nearly a decade after the co-owned newspaper and WGN were cleaved by the 2014 spinoff of Tribune Publishing from Tribune Media.

Skilling has the first Tribune weather page hung up on the wall of his home office.

While Skilling takes weather seriously, he also has a humorous side.

Those comedic chops were on display during a 2008 station-produced parody video, where WGN sports reporter Pat Tomasulo, taking literally a corporate campaign that Tribune employees were now the owners, decided to let Skilling go, unleashing the weathercaster’s dark side.

“If anybody owns this place it’s me, Tom Freakin’ Skilling,” the meteorologist menaced, chasing Tomasulo out of the weather center. “I could have you killed if I wanted to.”

In 2019, Dallas-based Nexstar Media Group became the new owners of WGN with the $4.1 billion acquisition of Tribune Media, creating the nation’s largest local TV station group.

Skilling has not been immune to some playful poking by other media personalities as well, including Steve Dahl, the onetime bad boy of Chicago radio, who created the parody prognosticator, Tommy Skillethead, soon after both hit the local airwaves in the late ‘70s.

The similarly upbeat Skillethead, who delivered Dahl’s forecasts for years, not only resonated with listeners, but also helped elevate the real Skilling to cult status in Chicago broadcasting.

“Whenever I did a weather forecast on the air, or we had crazy weather and we wanted to talk about it, Tommy Skillethead was there for us,” Dahl said. “It all just seemed to sort of work.”

Dahl said Skilling always got a kick out of the Skillethead character, and even engaged in some “surreal” on-air conversations with his alter ego.

Skilling has also been the object of good-natured internal sport at WGN. Materre and fellow anchor Ben Bradley created a game to play surreptitiously while Skilling delivered his often lengthy weathercasts, keeping score of his favorite sayings.

Skillingo, which was laid out like a Bingo card, included such Skillingisms as ”Katie bar the door” and “vorticity” (a measure of air rotation). If someone had “land-office business” on their card when Skilling uttered the phrase, they’d mark it down on their Skillingo card.

When Skilling learned of the game, he showed that in addition to his mastery of folksy sayings and meteorological terms, he possessed a self-deprecating sense of humor.

“He loved it,” Materre said.

Skilling is also not afraid to cry, even on camera.

In 2017, Skilling became so emotional while viewing a total solar eclipse at a Carbondale beach in southern Illinois, he choked up during his live segment, sending it back to the Chicago studio with an apology.

“This is amazing,” Skilling said, high-fiving and hugging fellow viewers as day suddenly turned into night.

Those who know him best, say Skilling’s on- and off-air personas are one and the same.

Bill Snyder, 51, Skilling’s longtime weather producer, started as an intern in 1996 and was hired by WGN the following year, helping put together everything from the Tribune weather page to the TV forecasts.

“He’s genuine,” Snyder said. “What you see on TV is what you’re going to get on the street. He loves Chicago, he loves his viewers, he loves his readers. There’s nothing fake or pretentious when it comes to Tom.”

Those qualities have connected with viewers across generations, as evidenced by the enthusiastic crowds that have met Skilling during what amounts to a farewell tour in February.

On Feb. 2, Skilling trekked before dawn to northwest suburban Woodstock, filming location of the 1993 “Groundhog Day” movie, to participate in the annual weather forecasting event it depicted. The faux festival has grown so popular it rivals the original in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.

Hundreds of fans packed the town square, including Karen Trannel, of Crystal Lake, who brought her husband, Jason, and two daughters, Madeline and Abigail, to celebrate her 50th birthday and see her favorite weathercaster – Skilling, not the groundhog.

“I grew up with Tom Skilling and my mom and dad would watch him, my girls now watch him, my husband watches him,” Trannel said. “We love Tom, and we’re excited for him and his retirement.”

Huddled behind the gazebo stage during the groundhog extraction, the family was unable to see Skilling, but close enough to hear him announce that Woodstock Willie did not see his shadow, which elicited cheers from the crowd with the promise of an early spring.

When the ceremony ended, Trannel made her way to the gazebo stairs, carrying a red homemade sign declaring, “It’s my 50th Tom! Let’s take a Pic!”

Skilling’s handlers obliged and her birthday wish came true. Trannel remained starstruck long after Skilling and Willie had departed the stage.

“He is such a wonderful man,” she said. “And he’s so kind and you could just tell that he truly loves what he does. There’s nobody like him.”

Skilling’s rise to local weather stardom on Chicago television was, for a time, overshadowed by his brother Jeff’s national notoriety as the disgraced former CEO of Enron, the Houston energy company which collapsed amid an accounting scandal in 2001.

Enron’s bankruptcy put thousands of people out of work and wiped out billions in valuation for investors. When the news broke, it was hard for many Chicago viewers to connect the affable weathercaster with America’s corporate villain du jour.

The ordeal took a great toll on the Skilling family.

In February 2005, their father suffered a stroke and head injury when he fell on a sidewalk in Aurora amid the massive publicity surrounding Jeff’s imminent trial. He died at the age of 83 in December 2006 – two months after his son was sentenced to a lengthy prison term.

Their mother, Betty, died in January 2008, also at the age of 83.

“That was a gut punch for the whole family,” Skilling said. “And it’s one of the saddest moments in my life. I buried two parents who in their final years had to live with that. And it breaks my heart that they did, because they were good people.”

Convicted of conspiracy and securities fraud, Jeff was sentenced to 24 years in federal prison. He was released in 2019 after serving 12 years.

Despite family challenges and the rise of 24/7 weather apps, Tom never missed a broadcasting beat, delivering a daily master class in meteorology that not only told viewers when they needed a raincoat, but why.

That forecasting acumen may have played a role in Skilling’s decision to retire, which he first announced in October.

“I started having some vertigo issues,” Skilling said. “I just view that as signals my body was giving me that maybe it’s time to slow down a little bit.”

Skilling, who underwent gastric bypass surgery in 2020 and lost 125 pounds, said his health is generally good.

During retirement, Skilling said he intends to spend more time at his homes in Alaska and Hawaii, but has no plans to leave Chicago.

He also would like to keep his hand in TV projects, perhaps creating longer-form specials for WGN, with climate change among the likely subjects.

Another idea he is considering is to create climate change tours to Alaska, where visitors can see firsthand the impact on glacial fields and other sites in his second-home state.

“I’ve been going to Alaska since 1980,” Skilling said. “The change that’s going on in the arctic latitudes is happening at three to four times the rate elsewhere.”

Suppelsa, who retired to a Montana cabin in 2017 after 25 years in TV news – the last 10 as evening anchor at Ch. 9 – had some advice for his former colleague.

Make no big plans, at least not right away.

“Take your time, do not make any drastic decisions, especially in the first six months,” said Suppelsa, 61.

Suppelsa is planning his first visit to Chicago in seven years to join colleagues at Skilling’s final weathercast. It will be, in many ways, a family reunion.

Never married, Skilling is a proud uncle and recounts the accomplishments of his nieces and nephews with great joy. But after 46 years on the air, co-workers and Chicago viewers are all members of his extended TV family.

“I’ve been married to this profession,” Skilling said. “I was married to my work.”

rchannick@chicagotribune.com