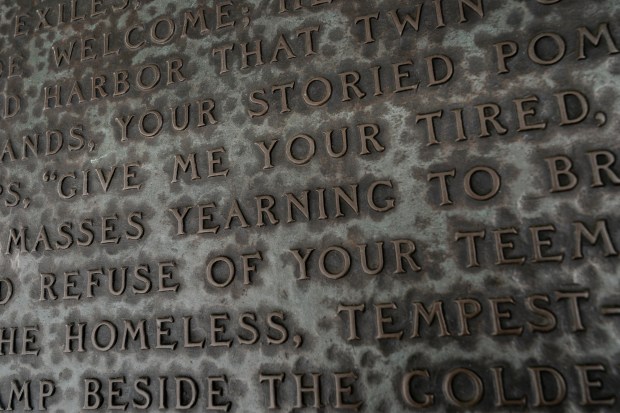

The Tribune applauded when the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 revoked a commitment symbolized by the Statue of Liberty and spelled out by a plaque on its pedestal:

“Give me your tired, your poor

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

Emma Lazarus wrote those lines in 1883. A well-fixed New Yorker, she was inspired by the myriad Jews seeking refuge from the poverty and persecutions of the Old World.

But a century ago the Tribune strained its credibility by assuring readers the Johnson-Reed Act — which drastically reduced opportunities for immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe — wasn’t intended to target Jews:

“The discrimination is not against Jews as such, but against peoples who colonize, develop ghettos, and do not melt in the melting pot.”

The issues over immigration dominating headlines today are not all that different from those of the earliest 20th century, when millions of people from the overcrowded European continent crossed the Atlantic for a bid at a better life in America.

Already in 1910, the Tribune lamented a changing U.S. that was increasingly alien to old-stock Americans. A reporter sent to observe cases in Chicago courtrooms told readers he heard scarcely a word of recognizable English.

“Shattered syllables, disconnected consonants and fractured verbs were sounded in Judge La Buy’s courtroom,” the reporter noted. “Justice La Buy has passed judgment on cases in which the Polish, French, German and Hebrew languages were spoken.”

During one of the day’s trials, the clerk struggled with the names of the litigants and five witnesses. “An attempt to pronounce the names of two others whose testimony was desired was abandoned as futile, and the men were designated as Frank and John Doe.”

At the Maxell Street Police Station, the reporter noticed: “Several of the policemen of the precinct, while unable to speak more than a few words of the ghetto language, can understand and translate the statements of witnesses, and their attorneys. A few of the policemen have been assigned to the foreign settlements for years, and during their working hours hear only the languages of the ghetto.”

On the eve of a vote on the 1924 immigration bill, the Tribune upped the ante with an outlandish headline: “POLAND SEEKS TO SEND U.S. HER TROUBLE MAKERS.”

“The Polish government hoped to turn its minorities over to the United States for safekeeping,” the accompanying story explained. “As a result of that policy 60,000 of the minorities, about 90 percent of this number being Jewish, have registered at the American consulate in Warsaw today and are waiting for their visas.”

When the Brooklyn Eagle rejoiced that the Johnson-Reed bill seemed headed for defeat, the Tribune took it as a sign that Brooklyn was a lost cause. The Eagle reported that, “Catholics, Protestants and Jews joined in a meeting to assail the bill.”

“It would be difficult to find better arguments in favor of Johnson’s bill than those offered by the Eagle against it,” the Tribune coyly wrote.

Its editors firmly believed that America’s manifest destiny was to be a white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant country, and feared its heritage was endangered.

“Unrestricted immigration in the years prior to the Great War was rapidly turning many of our greatest cities into foreign colonies,” the Tribune wrote. “It was especially noticeable that in those cities (immigrant communities) were composed largely of Southern and Eastern Europeans.”

The prequel to the Johnson-Reed Act dates to the formation of the Immigration Restriction League in 1894. Its founders were “Boston Brahmins” and similar East Coast notables. Among them was Henry Cabot Lodge, a Massachusetts senator and author of “The Great Peril of Unrestricted Immigration.” Its premise was that America’s prosperity was indebted to Lodge’s belief that its Yankee-stock founders were racially superior.

“You can take a Hindoo and give him the highest education the world can afford,” he wrote, “but you cannot make him an Englishman.”

He fine-tuned his racial theory by rating Northern Italians “more Teutonic” than the Southern Italians he considered unfit immigrants.

When a bill to restrict immigration was debated in 1896, Lodge argued its beneficiaries would far exceed the membership of the elite social class to which he belonged. “If we have any regard for the welfare, the wages, or the standard of life of American workingmen, we should take immediate steps to restrict foreign immigration,” he said in a speech to his fellow senators.

The bill provided that immigrants had to be literate. The league thought that the demonstration of an ability to read 40 words in any language would favor immigrants from western Europe over those from Southern and Eastern Europe, where access to education was rarer.

Congress approved the 1896 bill, but President Grover Cleveland vetoed it. Similar bills were vetoed in1913 and 1915. In 1917, Congress overrode a presidential veto, but it failed to provide the barrier to entry advocates had hoped for because of improved literacy rates in Southern and Eastern Europe.

The following year, the league found a formula to achieve its goal: Setting quotas for immigrants based on a percentage of their countrymen here on a set date. By that standard, admissions for Southern Europeans would have fallen dramatically, while substantially more Northern Europeans would be allowed into the country.

The league’s formula was written into the Emergency Quota Law of 1921. It was hastily cobbled together amid fears that the United States would soon be drowning in a tidal wave of refugees created by World War I and the Russian Revolution. It was renewed in 1922. So when Congress debated permanent legislation in 1924, the question was no longer whether there should be immigration quotas, but how they might be adjusted.

Representatives of states with sizable ethnic minorities were either outvoted or fought a rear-guard defensive action. The Johnson-Reed bill was passed by the House by a vote of 323-71.

When 20 of New York’s 22 Democratic representatives opposed the bill, the Tribune wasn’t surprised.

“In population and in many of its social phases, New York is largely foreign,” the paper noted. Ergo its politicians think “whatever may be good for the aliens within our gates, or knocking at the gates, is good the country.”

Illinois Rep. Adolph Sabath tried making the best of his constituents’ ill fortunate situation. He had been a judge in one of the Chicago courtrooms where English was a rare commodity.

“Some of you maintain that this bill is not discriminatory,” he said. “I say that to discriminate is our right, but that when we discriminate, we ought to discriminate fairly.”

He wanted to substitute 1910 for 1890 as the baseline of immigrants in the U.S. to calculate how many of their countrymen would be entitled to join them. In 1910, immigration was in full steam, so as a reference point it would yield more visas than 1890 for Eastern and Southern Europeans.

Sabath lost the battle, which the Tribune proclaimed a “a Nordic victory.”

As enacted, the Johnson-Reed Act also barred entry for most Asians, a provision insisted upon by Californian business owners and trade unions who didn’t want Asian competitors.

Ellis Island, where nearly 12 million immigrants landed, was phased out as a way station for incoming migrants. For many, the spirit of welcome it symbolized was obsolete. The Johnson-Reed Act also led to unforeseen or discounted tragedies: Visas denied Jews persecuted by Nazi Germany, Holocaust survivors and refugees fleeing the Iron Curtain Joseph Stalin dropped on Eastern Europe.

Yet even as its effects were manifest, the Tribune didn’t budge from its support of the Johnson-Reed Act. In 1939, after the Great Depression left millions of Americans unemployed and destitute and with a war that would devastate Europe looming, the paper voiced opposition to a plan to admit 20,000 refugee children.

“The choice seems to be between helping those who are starving in Europe and those who have been pauperized here by a ruthless economic system,” the paper editorialized.

Curiously, the paper’s position was underscored with the words of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who Col. Robert McCormick, the Tribune’s editor, detested: “One third of the nation is still ill-fed, ill-housed and ill-clothed.”

They were the theme of FDR’s New Deal, a social safety net that, the Tribune preached, would bankrupt America financially and morally.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com