Much of south suburban Chicagoland is in an uproar over a dramatic spike in residential property tax bills.

In much of the southland, median homeowners’ second installment bills for the 2023 tax year (due Thursday) jumped nearly 20% over last year, according to Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas’ office. But for many, the damage was far worse than that. Median tax hikes were 30% or higher in 15 south suburbs, 13 of which are predominantly African American, according to the treasurer.

Anecdotally, there are homeowners who saw their bills double or worse, adding potentially thousands to their annual tax bill. Anger is everywhere, and politicians from local lawmakers to the governor are in the beginning stages of a scramble to respond.

What’s mainly behind the sticker shock is a substantial reduction in commercial property values, reflected in last year’s triennial reassessment for the region, that has put far more of the property-tax load on homeowners, whose properties have appreciated even as commercial values have dropped.

Property taxes are a zero-sum game. Taxing bodies get the money they approve no matter what; all assessments do is divvy up the responsibilities. And when commercial values fall and residential values rise — a rare occurrence historically — households pay more of the freight.

The calamitous increases in the southland, a region where incomes on average are significantly lower than the rest of metro Chicago, are a portent for what’s likely coming next year in the city itself. The triennial assessment of Chicago’s properties is well underway, and the dynamic that struck the south suburbs is more pronounced in the city. Businesses make up far more of the city’s property tax base than in the suburbs, an effect that in the past has made Chicago’s property taxes more affordable than its suburban counterparts.

The aftermath of the pandemic struck downtown Chicago like a tornado, as the work-from-home evolution crushed office building values. Rarely a week goes by without some major office building defaulting on its debt, and ownership handing the keys to their lenders. Downtown retail, too, has suffered badly, with vacancy rates topping 30% in the Loop. North Michigan Avenue’s vacancy rate likewise exceeds 30%. The sight of so many empty storefronts on the Magnificent Mile is both remarkable and depressing.

On its face, the intense downtown real estate woes should scare Chicago homeowners about what next year’s tax bills will be.

In a recent meeting, Cook County Assessor Fritz Kaegi told us not so fast. Yes, downtown Chicago’s office buildings make up about 20% of the city’s tax base. But Class A offices — typically newer buildings commanding the highest rents in the central business district — generally are retaining their value, he said. Class B and C buildings are where most of the pain lies, he said, but they make up only about 5% of the city’s tax base.

Homeowners are also protected from bearing much more of Chicago’s property tax burden by many Chicago office buildings being in tax increment financing districts, where changes in assessed value aren’t reflected for now in what is paid to various taxing bodies like Chicago Public Schools, the city of Chicago and the Chicago Park District.

The assessor is early in his assessment process for the city, but three areas that had been completed when Kaegi met with us — Rogers Park, Lakeview and West Township — showed commercial values rising slightly more than residential, which is up about 20% on average over the past three years, Kaegi told us. That’s an early positive sign that residential property tax bills in Chicago won’t jump like they have in the south suburbs.

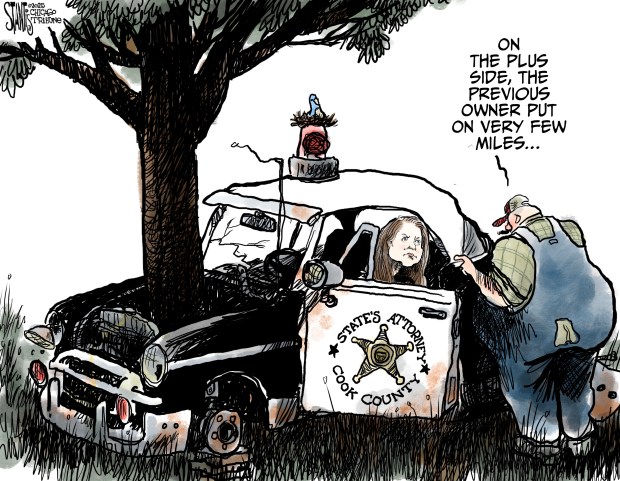

But — and this is a very big but — Kaegi’s office isn’t the final word on property assessments. His work is subject to appeal with the three-member Cook County Board of Review. And Kaegi over the past several years has been at bitter loggerheads with the board, which has reduced commercial assessments when businesses have appealed far more than Kaegi believes is warranted.

Those commercial reductions have meant that residential property taxes correspondingly have increased. Kaegi blames much of the south suburban debacle on the Board of Review. Defenders of the board say they’re simply responding to what’s happened in the marketplace to commercial property values.

The battle between Kaegi and the board shows no signs of calming down, despite our past optimism, and that’s bad news for Chicago taxpayers. The commercial property declines in Chicago arguably have been more dramatic than elsewhere in the region. If the board doesn’t agree with Kaegi’s relatively sanguine view of how business property owners in the city have fared post-COVID — and it’s a safe bet it won’t — homeowners need to be prepared for significant increases beginning next year.

Mayor Brandon Johnson has said repeatedly he won’t raise the city government’s property tax levy. Property taxes already are a red-hot issue with the mayor’s base on the South and West sides, with longtime residents (often seniors on fixed incomes) increasingly pressured to sell their homes and leave the city because they can’t afford the taxes. He will confront what is likely to be a significant fiscal hole this coming fall when he and the City Council have to produce a budget.

Even if he manages to balance the budget without raising property taxes, it won’t save the city’s homeowners from the coming fights over the competing interests of commercial and residential payers, not to mention all the other disparities and illogicalities in the not-so-wonderful world of property taxes in Cook County.

Get ready for property taxes to become an even bigger political war.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.