How do you tell when people are overburdened by property tax bills?

You could listen to what people are saying, of course, or make a comparison with rates for comparable property in other states. But a better way is to look at what percentage of homeowners are actually paying their property tax bills in a timely fashion.

As with any governmental bill, some people get behind, often through no fault of their own. But while late fees are ubiquitous from utility bills to parking tickets, people often hold off on those bills in the hopes of catching up later: In a worst-case scenario, they know that the worst the cable people can do is cut off their service. And you can find another one.

But property tax bills don’t work like that. If those bills are not paid, the homeowner is hit with immediate interest-rate charges, as per state law. The amount of interest due was reduced earlier this year from an egregious 18% to 9%, thanks mostly to the efforts of Cook County Treasurer Maria Pappas. But 9% still is 9%. More importantly, if you’re not careful, an unpaid property tax bill can result in your property slipping into the Annual Tax Sale, or even the dreaded Scavenger Sale (now held only if ordered by the Cook County Board). Pappas’ office has done good work to make the system work better for property owners, but our point here is that there remains a significant disincentive to not paying your property tax bills. People tend to prioritize them. So if they’re not paying them, that’s a pretty good indication of financial distress.

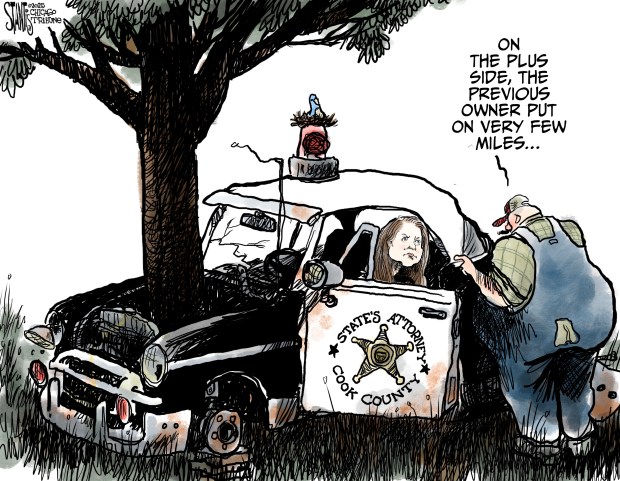

Pappas’ office issued a report Wednesday noting the declining rates of property tax compliance, especially and not coincidentally in the south and southwest suburbs that have been walloped by big increases in their bills: a median rate of increase of close to 20%, year over year.

Something else also contributed this year: two due dates landed much too close together.

Many people sock away money for their property taxes (if they aren’t paid as part of their monthly mortgage bill) over several months. In 2024, you had just saved your cash for one bill when the next one arrived in your mailbox. We’ve complained before about the shifting due dates of Cook County property tax bills, typically explained away by the blame-shifting authorities as driven by technology issues, and we’ve been promised improvements by the assessor and others. But there’s evidence here of the impact of an unpredictable billing cycle on people who have to actually pay those bills.

So what happened? Simply put, Cook County property tax delinquency in 2024 rose to the highest levels in more than a decade. Compliance rates (about 95%) may still seem high, but Pappas’ office said that still meant an additional 22,500 Cook County property owners became delinquent, meaning that $225 million went uncollected. And the compliance rate showed huge geographical variation. In wealthy pockets, it remained high. But in communities such as Robbins, Harvey and Ford Heights, around half (or more) of all the property tax bills went unpaid. Harvey, the largest of those three communities, is especially troubling. Of the 13,000 bills sent out, well over 6,000 have not yet been paid.

Cook County nominally benefits if people pay their property tax bills late because the government pockets that legally required interest, swelling public coffers, but that obviously comes at the expense of homeowners. Governments do not benefit at all if the properties have to be sold off — a process that occurs about 13 months after the due date. It’s true that not all of these properties are owned by regular folks and that many of these bills will be paid before any forced sale — the report looks at the collections rate 31 days after the due date — but a hefty chunk of Cook County residents who can least afford to do so clearly are being forced to cover high interest on top of their already steep bills. Or they are headed into default and possibly losing their homes.

Low collection rates, of course, hamper local governments from collecting the money they need to provide services to residents. This problem in the south and southwest suburbs, where collection rates long have been lower than elsewhere in Cook County, is looking to us like a growing crisis. Pappas’ office notes the low rates of collection on properties where a senior exemption is in place, suggesting older folks are over-represented among those under duress.

We should all pay our property taxes, of course. They’re part and parcel of owning a piece of property, and losing a property into which you have sunk your money can torpedo people’s plans for financing their retirements.

That said, there is evidence here that a large number of homeowners are tapped out and that the inability of Cook County to space out its bills had an adverse effect on ordinary people. That should never be allowed to happen again.

Meanwhile, any municipality looking to solve its fiscal problems by raising property taxes even more should take a look at all of these unpaid bills. They send a message that some folks cannot afford to pay the taxes on their own homes presently, let alone even higher levies.

No responsible government wants to see that happen. And that’s why taxing bodies of all kinds have to tighten their belts before asking homeowners for more.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.