When aggressively progressive city councils make egregious demands on businesses, usually by passing legislation that ignores market realities, they expect those corporations just to fall in line. But they forget that national companies have another viable option: the choice to offer their wares elsewhere.

In business school, they call that leverage.

Take the fascinating situation in Minneapolis where the two major ride-share companies, Uber and Lyft, fierce competitors generally, both said they will exit the market, effective May 1. That’s because the far-left council has imposed a minimum level of compensation for drivers ($1.40 per mile and 15 cents a minute) that both ride-share companies say makes their business unsustainable. The radicals on the council say that’s what those rates should be to ensure that drivers, often recent immigrants, always receive the city’s minimum wage of $14.50 per hour after the drivers’ expenses on gas, maintenance and the like. The ride-share companies long have viewed their drivers as independent contractors, sometimes making less than that and, in busy periods, both sides agree, making far more. Even if you buy the idea of requiring minimum wage every hour, the calculation to arrive there is, unsurprisingly, contested. For one thing, it does not take tips into account. For another, it doesn’t amply reflect how many drivers work for both Uber and Lyft at the same time.

Minneapolis has a progressive mayor in Jacob Frey, who had a moment in the public spotlight in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder. But this legislation was too aggressive even for him. He vetoed the measure. The council overrode him.

You might well ask, so what if Lyft and Uber leave? There are cabs. But here’s the rub: Minneapolis now has somewhere between 14 and 39 licensed taxi drivers, depending on which local media outlet you trust. That’s not a typo; such is the current consumer preference for ride-sharing. As recently as 2015, there were over 1,500 Minneapolis cabbies. Some 98 out of every 100 are gone.

Meanwhile, Lyft and Uber have over 10,000 current drivers in the market, serving up hundreds of thousands of trips annually, many to the airport.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz has expressed his adult-in-the-room concern about the council shenanigans, much as Gov. J.B. Pritzker has been wont to do with Mayor Brandon Johnson and the radicals on the Chicago City Council. Who wants to schedule a big convention in town with no convenient late-night transportation?

As we write, there are rumblings to our north that the council might reconsider its veto and return to the negotiating table, which is, of course, the only viable way to go here. Hard-core council members argue that Uber and Lyft’s departure will open the door to a new local ride-share operation and/or will benefit public transportation. But it’s hard to see how any startup could scale up by May 1. As you might expect, some of the council fans of government ownership of most everything under the sun want to see the city itself getting into the ride-share business, which is the Minneapolis equivalent of the city of Chicago wanting to compete with Jewel and Aldi. What could possibly go wrong?

It’s time for some realism in Minneapolis. It cannot lose the services of Uber and Lyft and adequately serve its nondriving population, and the council can’t expect them to operate unprofitably, whatever the size of those public companies. They’re businesses after all.

Should these companies have been permitted to dominate so absolutely and cab companies with fixed rates allowed to disappear? That’s a fair question, and we’ve written disapprovingly in the past about how the ride-share giants in the early days were allowed many unfair advantages over cab companies. Any fool can see that state and city regulators were seduced by the promise of initially low prices, only to watch helplessly as fares rose.

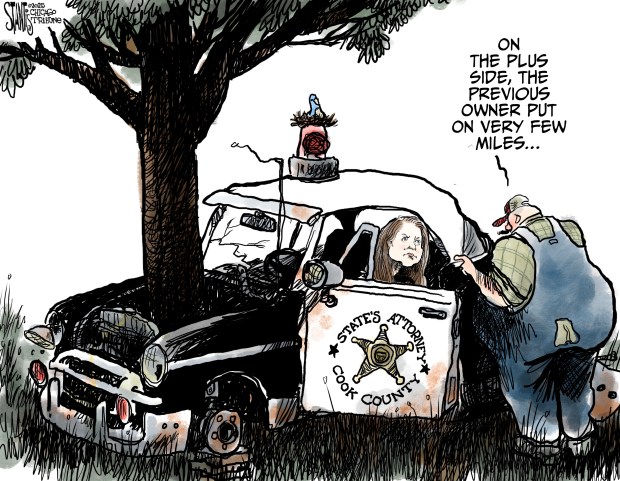

But that Uber has driven off, and the facts on the ground now have to be faced. And negotiated.

It’s not hard to see who has the upper hand.