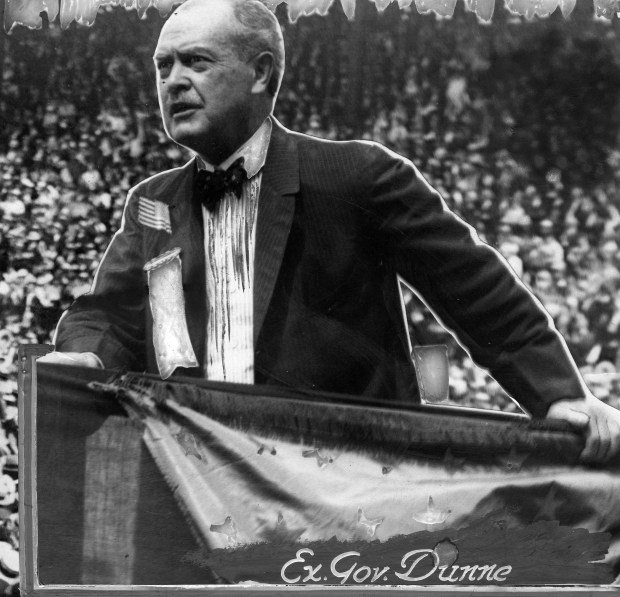

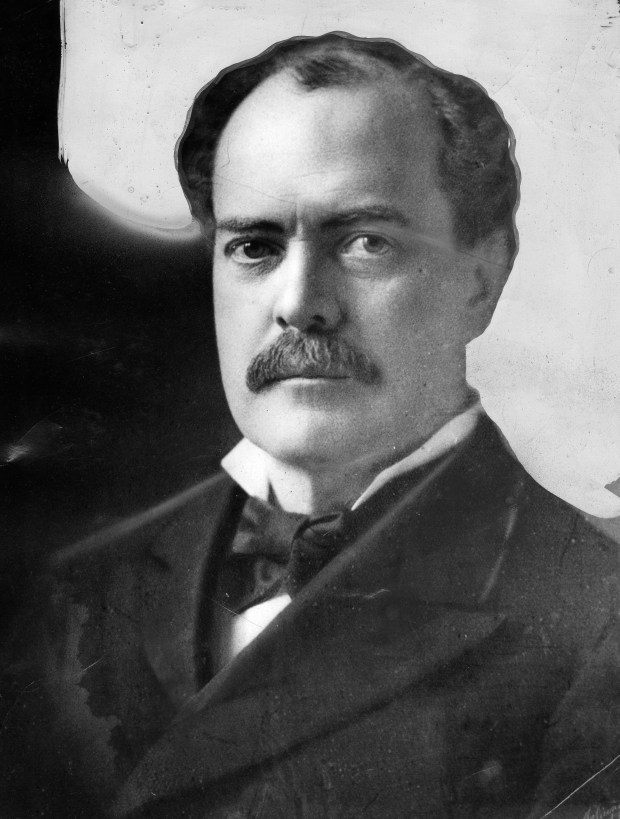

Having been mayor of Chicago and governor of Illinois, Edward F. Dunne went to France in 1919 to bug President Woodrow Wilson about Ireland.

Wilson was attending the Paris Peace Conference that was drafting a treaty to end World War I. In an address to Congress the previous year, Wilson stressed “14 Points” for a just and lasting peace. One theme was self-determination for minority populations.

Dunne was there to argue that the Irish were among those so entitled, and he was getting the runaround. “Mr. Walsh and Mr. Dunne practically are hopeless of getting a hearing for the Irish republic before peace is signed,” the Tribune reported on June 9. Frank P. Walsh was an Irish nationalist who was co-chairman of the National War Labor Board under Wilson.

“This provision applies only to small states, not the Great Powers,” the leaders of the post-World War I “Big Four” countries — the U.S., Italy, Great Britain and France — had said.

Dunne, the American-born son of an Irish nationalist and the only person to serve as both Chicago’s mayor and Illinois’ governor, had taken up the cause championed by his father. He was a founder of the Irish Fellowship Club along with several regular lunch mates at Vogelsang’s Restaurant in Chicago.

The club endures to this day and continues to host a St. Patrick’s Day dinner. It was quite a coup when President William Howard Taft accepted an invitation to the club’s 1910 St. Patrick’s Day banquet at the La Salle Hotel.

“The President, shamrock in lapel, sat in a huge tapestried chair which had been made especially for the occasion,” the Tribune recalled in a 1951 retrospective.

“Tributes by Taft to the Irish people, tributes by officers of the Fellowship Club to Taft, and performance of Irish music and the recitation of Irish poems sped the time so pleasantly that he could not leave the city at 10:30 as he had planned.”

The president was supposed to address the gathering while standing on Irish sod. It was the brainchild of James Cleary, a Tribune reporter.

“Cleary had just returned from Ireland and knew a man who would be happy to ship some sod, complete with grass and shamrocks,” his newspaper noted.

The sod arrived on March 15 and was displayed in a side room just off the banquet hall. Police officers guarded it, and thousands filed solemnly past. “Many a man brushed back a tear at the sight,” according to the Tribune’s retrospective.

Then someone remembered that by tradition an American president never set foot on foreign soil. Were they thoughtlessly tempting Taft to break some law?

Previously police had chased off souvenir hunters, now they were told to look away. “In short order not a blade of grass, a shamrock ‘or a cubic inch’ of sod remained.” Taft spoke standing on a sparkling clean, non-Irish floor.

To expats, those bits of dirt bore familiar scents of their old country. “That was smell of air and rain and turf and corduroy,” James Joyce recalled in “Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” For him, it was “a holy smell.” Like so many other Irishmen, Joyce, a pioneer of modern literature, had left Ireland of his own accord, but still felt nostalgia for his homeland.

But Irish Americans also had painful memories of British colonialism. During the Great Famine of the 19th century, potato crops failed. A million Irish peasants died of starvation, and another million became refugees. Instead of sharing their harvest, the island’s English aristocrats exported it.

Others left with a price on their heads for trying to win independence by force of arms.

![Mayor-elect Edward F. Dunne and his family pose in front of their Austin neighborhood home in 1904 on the day he was elected mayor of Chicago. Dunne was inaugurated the following April. In the back row, from left, are Dorothy, Mr. Dunne holding Jeanette, Mrs. Elizabeth [Kelly] Dunne holding Eugene, Edward F. Dunne Jr holding Geraldine and Eileene. The front row, from left, is Maurice, Mona, Robert and Richard Dunne. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)](https://localbusinessheadlines.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ctc-l-dunne-5jpg-CT0134700677.jpg)

Dunne’s father immigrated to America in the late 1840s after a failed uprising. He and Dunne’s mother made it clear to their son which side they were on. They sent Edward Dunne to public school in Peoria because the Catholic church frowned on the Irish nationalists. For similar reasons, Edward went to Trinity College in Dublin.

“My father believed because Robert Emmett was a student there when he was executed and because they had statues of Oliver Goldsmith and Edmund Burke in front of it, that it must be a good school, so I was sent there,” Edward Dunne recalled years later.

Emmett was a nationalist leader at the turn of the 19th century. Goldsmith and Burke were literary luminaries. Dunne didn’t finish college in Dublin. His father was broke. By the time he died in 1921, he had given about $100,000 to the Irish nationalist movement.

Dunne’s family moved to Chicago and Edward Dunne graduated from Union Law School in Chicago. He subsequently emerged as the rarest of Chicago species: an honest politician.

His issue of choice was public transportation. Chicago was expanding so rapidly that there were always streetcar tracks to be laid. Permits had to be granted, and politicians traded their approval for money.

After vainly battling that entrenched system, Dunne dropped out of electoral politics.

But he couldn’t refuse his fellow reformers’ request to deliver to the White House “The Report of the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland.”

Headed by Jane Addams, the commission documented the horrors that followed the British refusal to grant home rule to Ireland. Marital law was enforced by the Black and Tans, as the soldiers were dubbed because of the color of their uniforms.

Irish guerrilla tactics made some British solders trigger-happy, as one example in the record shows: “Mr. Broderick of Chicago was in Abbeyfeale when a passing Black and Tan killed two boys leading their cows to pasture.”

The commission noted that the Irish objection to the British was long-standing: “The Irish people from age to age, almost from generation to generation, have contested England’s right to Ireland.”

Didn’t that require a response, given President Wilson’s embrace of self-determination? Walsh and Dunne couldn’t get a meeting with Wilson, but his top aide arranged passports for them.

When they caught up with Wilson in France, the president admitted that Ireland was experiencing a “great metaphysical tragedy.”

But he had assured the British ambassador he wouldn’t embarrass the U.S. ally by getting involved in the Irish issue.

They went on to Ireland, and met with the Irish Parliament. Their request to meet with imprisoned Sinn Fein members was denied by the British. But they bluffed their way into the notorious Mountjoy Gaol, a prison in Dublin.

Upon their return to New York, they were greeted by a huge crowd. Dunne spoke to a crowd of more than 25,000 at a Chicago rally.

The British press was furious with Prime Minister David Lloyd George for allowing Walsh and Dunne to visit Ireland. King George V made a rare intervention in a political issue. He questioned the wisdom of Lloyd George’s decision to let the Americans tramp around Ireland.

To recoup, Lloyd George said he would have nothing more to do with the American delegation.

Wilson followed suit by refusing any further help to American peaceniks. When the report was published, the Times of London derided it as “grotesque.”

Nonetheless, Britain began negotiating with the Irish nationalists. Their differences were echoed by debates in the Irish diaspora. In Chicago’s Medinah Temple, Dunne confronted a speaker opposed to giving the Irish loans to jump-start an economy drained by colonial exploitation.

“Every nation on Earth and every suffering people not in possession of nationhood can come to this country without protest to float loans to further their ambitions,” he thundered in 1920. “The Irish alone shall not be allowed to solicit funds for the building up of their destroyed industries and commerce.”

On Dec. 6, 1922, his parents’ dream came true. The parties agreed that some counties would remain in the kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

But the rest of the island would be the Irish Free State for which his father’s hero Emmet fought. The leader of a secret society at Oxford, Emmet refused to repent or explain himself to the court that sentenced him to death in September 1803. He asked that others, too, be silent.

“Let no man write my epitaph,” he said. “When my country takes her place among the nations of the Earth, then and not until then let my epitaph be written.”