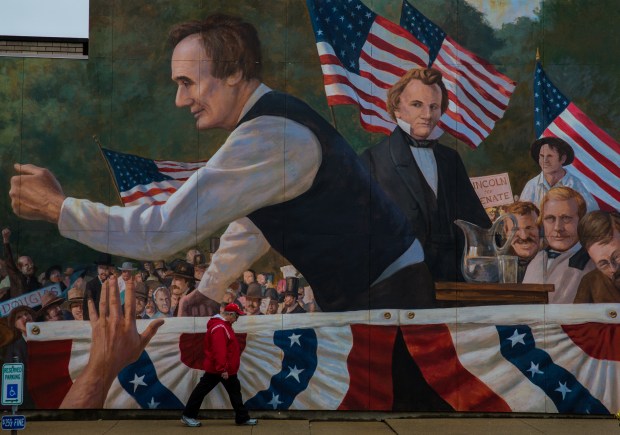

Editor’s note: The following lightly edited excerpt is from Chicago writer Edward Robert McClelland’s new book, “Chorus of the Union: How Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas Set Aside Their Rivalry to Save the Nation,” published by Pegasus Books. Here, McClelland takes us to Ottawa, Illinois, for the famed first senatorial debate between Lincoln and Douglas, two men who had first met years before in Vandalia. The debate took place some three years before the beginning of the Civil War.

Washington Square, Ottawa, Illinois, Aug. 21, 1858

In Ottawa, the site of his first debate with Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln made the grand entrance. On this hot, high summer Saturday, 15,000 spectators crowded the wooden sidewalks of Ottawa, converging on the village by canal boat, horseback, wagon, carriage and foot, doubling its population in an afternoon.

“The crowd had a holiday air,” a woman remembered half a century later. “It seemed out of place to me, for those were serious questions that Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Douglas were debating. The people paid for the gayety of that day in the horrors of the Civil War.”

Lincoln would not have the first word — as the incumbent, Douglas got the initial opening speech — but he would have the crowd. Ottawa lay in the Third Congressional District, represented by the abolitionist Owen Lovejoy, brother of the Alton newspaperman Elijah Lovejoy, whose 1837 lynching at the hands of a pro-slavery mob Lincoln had condemned before the Springfield Lyceum.

By the time Lincoln arrived at the Rock Island Railroad depot on the noon train from Chicago, thousands of Republicans had gathered outside. He was greeted with three cheers, then hustled into a carriage decorated with evergreen boughs and anti-slavery slogans. Slowly, the carriage rolled toward the mansion of Mayor J.O. Glover, preceded by a marching band and a bunting-draped float on which stood 32 waving girls, one for each state in the Union. Lincoln was being borne toward his destiny, for it was on this day, in this place, that he would become a national figure, whose arguments against the spread of slavery would be published in newspapers across the nation, adding his name to the list of Republican presidential contenders two years hence. Lincoln was not as well known as William Seward or Salmon P. Chase or Edward Bates, but unlike them, he was in a position to confront the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on his home turf.

Douglas received a more rustic greeting. He arrived by carriage from Peru, 17 miles downriver. At Buffalo Rock, a bluff overlooking the Illinois, the senator was met by farm wagons, buggies and a band. The procession, which straggled out for nearly a mile, guided him to Geiger House, Ottawa’s leading hotel, where he delivered a pre-debate speech. The Republican and Democratic bands arrived simultaneously in the town square. Trapped by the crowds, they expressed their partisan rivalry by playing as loudly as possible, trying to drown each other out. There was so much competition for space near the speakers’ platform, which had been erected beneath the square’s few trees, that spectators climbed onto pine planks. After a few boys caused part of the platform’s roof to collapse on the heads of the reception committee, marshals shooed the crowd back onto the baking grass.

The debate was scheduled for 2 o’clock, but it took Lincoln and Douglas so long to work their way through thousands of bodies that the speaking did not commence until half past. Lincoln jovially patted boys on the head, joking to one’s mother, “Here comes Douglas; a little man in some respects but a mighty one in others.” Once he reached the stand, he handed his heavy black frock coat to Ottawa’s Republican state senator, Burton C. Cook. “Hold it while I stone Douglas,” Lincoln told Cook.

The first stone belonged to Douglas, though, and he used it to attack Lincoln with what even he later admitted was a falsehood. Douglas began his opening speech by hearkening to the days when there had been two national parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, both equally devoted to the principle of allowing the states and the territories to decide for themselves the slavery question. Douglas attempted to defend the Kansas-Nebraska Act as consistent with the doctrines of both parties, but ended up admitting that he himself had shattered the nation’s comity on slavery: “Up to 1854, when the Kansas and Nebraska Bill was brought to Congress for the purpose of carrying out the principles which both parties had up to that time endorsed and approved, there had been no division in this country in regard to that principle except the opposition of the Abolitionists.”

Thus, anyone who opposed Kansas-Nebraska must be an abolitionist. Ottawa was in Yankee northern Illinois, but the crowd was nonetheless peopled with Democrats, who here cried, “Hurrah for Douglas” — music to the ears of Lincoln, who welcomed the chance to win them over.

From a pocket of his jacket, Douglas pulled a clipping from the Illinois State Register, a Springfield newspaper published by his friend and political ally Charles Lanphier. It was a report on a Republican meeting held in Springfield in October 1854 — a meeting to which Lincoln had been invited by the New York-born, Vermont-educated abolitionist Ichabod Codding, but had refused to attend.

Yet Douglas proceeded as though Lincoln had organized the meeting and drafted its platform, which dedicated the Republican Party to repealing the Fugitive Slave Law, prohibiting the admission of new slave states, abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia and excluding slavery from the territories. In fact, Lincoln endorsed only the last measure.

“My object in reading these resolutions,” Douglas declared, “was to put the question to Abraham Lincoln this day, whether he now stands and will stand by each article in that creed and carry it out” — just as he had (supposedly) intended in 1854.

“I ask Abraham Lincoln to answer these questions in order that when I trot him down to Lower Egypt I may put the same questions. I desire to know whether Mr. Lincoln’s principles will bear transplanting from Ottawa to Jonesboro?” — the site of the third debate, scheduled for Sept. 15, in pro-slavery southern Illinois.

After interrogating Lincoln, though, Douglas became sentimental toward his opponent, reflecting on their long acquaintance, which went back 25 years, to the days when “I was a school-teacher in the town of Winchester, and he a flourishing grocery-keeper in the town of Salem.” When Douglas and Lincoln met as young legislators in Vandalia, in 1836, Douglas “had a sympathy with him, because of the uphill struggle we both had in life.”

Douglas was never known to insult Lincoln personally. Lincoln’s first impression of Douglas from their Vandalia days was that he was “the least man I ever saw,” and he often made wisecracks about his rival’s stature, his dishonesty and his excessive drinking. Some of this had to do with their political fortunes: Lincoln envied Douglas’s success, while Douglas had little reason to take note of Lincoln, at least not until 1858. Some had to do with their attitude toward politics itself. Douglas was a practical politician, a professional who saw no reason to equate differences in policy with personal flaws. Lincoln was a moralist, more inclined to believe that a man’s political views were a product of his inner qualities. He saw slavery as a moral issue. Douglas did not. That was one of the central disagreements in this Senate campaign.

Douglas then used his opening speech to put Lincoln on the defensive over the issue of Black equality. Douglas, who had held statewide office longer than any Illinois politician, knew his constituents did not want slavery in their midst, but did not want emancipation, either, and for the same reason: both would have forced Whites to compete with Black labor.

“Do you desire to strike out of our state constitution that clause which keeps slaves and free Negroes out of the state, and allow the free Negroes to flow in, and cover your prairies with Black settlements?” Douglas asked, to cries of “No, no!” and “Never!” from the Democrats. “Do you desire to turn this beautiful state into a free Negro colony, in order that when Missouri abolishes slavery she can send 100,000 emancipated slaves into Illinois, to become citizens and voters, on an equality with yourselves? If you desire Negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the state and settle with the White man, if you desire them to vote on equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible for office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican Party, who are in favor of citizenship of the Negro.”

Douglas sat down, and a coatless Lincoln stood to reply. One reason the 1858 Illinois Senate debates are such a picturesque event in American history is the physical difference between the candidates. Two years hence, the spindly Lincoln would become, at 6-foot-4, the tallest man ever to seek the presidency. Douglas, 5-foot-4, with a massive head atop a swelling torso, like a pair of stacked cannonballs, would have been the shortest. Charles Dickey, the 16-year-old son of T. Lyle Dickey, a Douglas supporter who would later serve on the Illinois Supreme Court, noted the distinction not just between their physiques, but in their speaking styles: “Douglas had a deep bass voice which could be heard in the distance, but his enunciation was not distinct and only the crowd within a hundred feet could understand what he said. Lincoln on the other hand, had a high tenor voice and very distinct enunciation, so he could be heard and understood out to the extreme edge of the crowd.”

Douglas had thrown the Black citizenship accusation in Lincoln’s lap, giving him no choice but to reassure the crowd that he, too, believed in White supremacy. Throughout the campaign, Lincoln emphasized that he supported economic equality for Blacks, but not social or political equality — a distinction unlikely to win over Whites who felt threatened by cheap Black labor, be it slave or free.

Lincoln began his reply by quoting from an 1854 speech in Peoria. He had favored freeing all the slaves and deporting them to Liberia but realized “its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days.”

Africans had been enslaved in North America for 239 years. For the moment, the country was stuck with the practice of slavery — but not forever, Lincoln hoped. The country would be stuck with the Africans forever, but it should not follow that emancipation would put them on an equal footing with their former masters.

“I have no purpose directly or indirectly to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists,” Lincoln said, refuting Douglas’s charge that he was an abolitionist. “I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the White and Black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary, but I hold that notwithstanding all this. There is no reason in the world why the Negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he is as much entitled to those as the White man. I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.”

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.