According to an FBI report in 1923, Florence Kelley had been “a radical all the sixty-four years of her life,” a record America’s first female factory inspector credited in part to how she learned her ABCs.

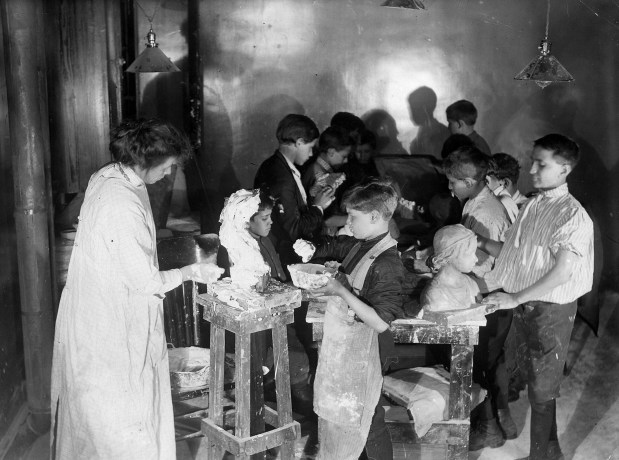

“Father had taught me to read when I was seven years old, in a terrible little book with woodcuts of children no older than myself, balancing with their arms heavy loads of wet clay on their heads, in brickyards in England,” Kelley recalled in her autobiography “Notes of Sixty Years.”

“They looked like little gnomes and trolls, with crooked legs and splay feet large out of proportion to their dwarfed frames.”

When Kelley’s mother and grandmother objected that her father was burdening her with conceptions beyond a child’s compression, he replied, “that life can never be right for all the children until the cherished boys and girls are taught to know the facts in the lives of their less fortunate contemporaries.”

The experience left Kelley with indelible images that eventually brought her to Jane Addams’ pioneering outreach with the impoverished residents of Chicago’s slums.

“On a snowy morning between Christmas1891 and New Year’s 1892, I arrived at Hull House, Chicago, a little before breakfast time and found there Henry Standing Bear, a Kickapoo Indian, waiting for the door to be opened,” Kelley recalled in her autobiography.

“It was Miss Addams who opened it, holding on her left arm a singularly unattractive, fat, pudgy baby belonging to the cook, who was behind-hand with breakfast. Miss Addams was a little hindered in her movements by a super-energetic kindergarten child left by his mother while she went to a sweatshop for a bundle of cloaks to be finished.”

Henry Standing Bear shortly returned to his tribe, but Kelley stayed on as a member of what came to be known as the Women of Hull House: Middle-class volunteers who lived and worked alongside Addams. Yet she didn’t share their conviction that women and children’s rights could be established by polite advocacy.

Reform required bare-knuckles politics, Kelley wrote in an article, “The Need of Theoretical Preparation for Philanthropic Work.”

“The appropriation of the surplus value created by the workers is the real cause of the need of any philanthropic work. If they were not ground down by competition to the bare means of subsistence, plundered systematically of the fruits of their labor, they would not furnish social wreckage, as they are doomed to do.”

As her words echoed Karl Marx, Kelley was denounced as a subversive. She corresponded with Marx’s collaborator, Friedrich Engels, and made an English translation of his indictment of capitalism, “The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844.”

Nonetheless, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1953 wrote that Kelley had “the largest single share in shaping the social history of the United States during the first 30 years of this century,” crediting her with helping to secure legislation “for the removal of the most glaring abuses of our hectic industrialization following the Civil War.”

She created the “White Label” designation for stores that treated employees fairly and was a charter member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

W.E.B. Du Bois, the N.A.A.C.P’s founder, said of Kelley that, “save for Jane Addams, there is no other social worker in the United States who has had either her insight or her daring as far as the American Negro is concerned.”

It was a trait that ran in her bloodline. Noticing that her Aunt Sara never put sugar in her tea, Kelley asked why.

“Cotton was grown by slaves and sugar also,” she replied, ”so I decided many years ago never to use either and to bring these facts to the attention of my friends.”

Kelley’s father was a congressman from Philadelphia and an outspoken abolitionist. His deep rumbling voice, the Tribune said, made his speeches sound “like an eloquent graveyard.”

A pro-slavery congressman slashed William Darrah Kelley’s arm when their paths crossed in a Washington hotel. After the Civil War, he was speaking in Mobile, Alabama, when Ku Klux Klan members opened fire. He ducked, but the man standing next to him was killed. From then on, he carried a billy club to speaking engagements.

Florence Kelley got a bachelor’s degree at Cornell University and wanted to study law at the University of Pennsylvania, but was rejected “by reason of her gender.” She eventually got her law degree from Northwestern University, but first studied at a university in Switzerland, an egalitarian country. “Her mind was ‘tinder awaiting a match,’ and the match was the student socialist movement in Zurich,” she recalled in “My Novitiate.”

Her father had willy-nilly prepared her for the Left’s message. “He said the duty of his generation was to build up great industries in America so that more wealth could be produced for the whole people,” according to her autobiography.

“The duty of your generation,” he told his daughter, “will be to see that the product is distributed justly.”

She met a Socialist medical student in Zurich. They married and settled in New York, where she campaigned for women and children’s rights. When the relationship soured, she took their three children and fled to Chicago.

The children were placed in the Winnetka household of Henry Demarest Lloyd, a former Tribune editorial writer and future author of “Wealth Against Commonwealth,” an exposé of monopolistic capitalism’s corruption of democracy.

Kelley became a Hull House resident. “I am conducting a bureau of woman’s labor and learning more in a week, of the actual conditions of proletarian life in America, than in any previous year,” she wrote to Engels in April 1892.

Her work caught the eye of John Peter Altgeld, Illinois’ reform-minded governor. He appointed her the state’s chief factory inspector, and her efforts finally bore fruit.

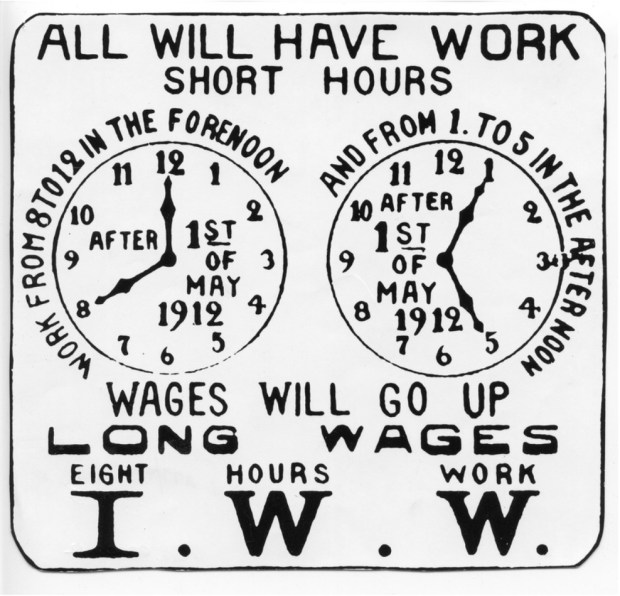

“We have at last won a victory for our eight-hours law,” she wrote to Engels on New Year’s Eve 1894. “The Supreme Court has handed down no decision sustaining it, but the stock yard magnates having been arrested until they are tired of it, have instituted the 8-hours day for 10,000 employees, men, women, and children. We have 18 suits pending to enforce the 8-hours law and we think we will shall establish it permanently before Easter.”

While that forecast was wildly optimistic, the Tribune reported Kelley still had her fire in 1923. A story about the National Conference of Social Work noted that one speaker was: ”Mrs. Florence Kelley of New York, who startled the meeting with the vigor of her attack on the recent decision of the Supreme Court holding unconstitutional the minimum wage law for women.”

She had moved from Hull House to the Henry Street Settlement on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As secretary of the National Consumers League, she got the Supreme Court to uphold a law limiting the number of hours employers could require women to work.

She hired Louis Brandeis to represent the Consumers League in the case of Muller v. Oregon. Later he would be a Supreme Court justice, but in 1909 he was a young lawyer with a revolutionary idea. Instead of resting his case on fine points of law, he argued that long workdays imperiled a woman’s health.

He won, but the victory was curtailed by a1923 Supreme Court decision Kelley railed against. In Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, the court found that the District of Columbia’s minimum wage law violated an individual’s rights.

But the “Brandeis Brief,” which Kelley helped him create, set a new standard for judging a law’s constitutionality: its effect on people. Thurmond Marshall won the 1952 civil-rights case, Brown v. Board, with evidence of the corrosive effect of a segregated school on a Black child’s sense of self-worth.

Kelley didn’t get to see that milestone. She died in 1932, shortly before President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave life to her ideals: the1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which established an eight-hour workday and kept children out of factories; and the 1935 Social Security Act, which freed senior citizens from the inevitability of poverty.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com.