The last time we saw James Bond he was being blown to bits.

Sorry, but “No Time to Die” is three years old now and the spoiler statute of limitations has expired. Chris Corbould blew him up. He’d been trying to blow up 007 since 1977, beginning with “The Spy Who Loved Me.” We met the other day at the Museum of Science and Industry in Hyde Park, which has a new exhibit of Bond gadgets and Bond vehicles and Bond-centric lessons in physics, technology, deception and the staging of insanely large explosions. It’s called “007 Science: Inventing the World of James Bond.”

Corbould, an Oscar-winning special effects supervisor, brought along Meg Simmonds, the director of archives for EON Productions, the British family business that makes James Bond movies. Simmonds’ job is to gather artifacts from a Bond production and catalog every piece in one of four warehouse facilities they keep in the London area. After Corbould blew up James, one imagines that Simmonds pocketed 007’s cufflinks.

She lent the MSI … oh dear, James, where do we begin: one suitcase nuke, one fake Faberge egg, a garden rake that doubles as a metal detector, a flute that doubles as a microphone, jetpacks, bionic eyeballs, leg casts that fire rockets, poison-tipped sandals.

Remember the stainless steel teeth worn by Richard “Jaws” Kiel? They’re here, too.

Simmonds told me, “Those teeth were molded by a dentist, and yet too painful to wear for any actual period of time. Anderson Cooper came by to do a segment on our 50th anniversary and he actually put those teeth into his mouth. Of course, they barely fit.”

Ew.

“Yeah, I know.”

“007 Science,” created as a collaboration between MSI and EON, is a showcase for the incredible and the ridiculous — but also, seriously, a decent reminder of both the exacting standards it takes to create those ridiculous things and how prescient the movies — and James Bond movies, in particular — have been about predicting future technologies. In fact, there’s so much everyday tech in this show that Simmonds insists was introduced to movie audiences via Bond — pagers, cell phones, bulletproof vests, eyeball scanners — the fictional spy seems to take a place alongside H.G. Wells, who predicted email, A-bombs, genetic engineering and automatic doors, and “Star Trek,” which imagined flat screens, voice-activated tech, flip phones and tablet computers.

But that ski pole that doubles as a gun — never caught on.

“The ski pole was your first gadget,” Simmonds said Corbould, who replied, “It was! Made it when I was just 17, starting out.”

Corbould won an Academy Award for the special effects in Christopher Nolan’s “Inception,” and also did special effects for Nolan’s Batman films, a couple of “Star Wars” movies, the original “Superman” series, the Who’s “Tommy” and the previous 15 Bond films. He holds the Guinness World Record for staging the biggest explosion in a movie. He earned that distinction for the 2008 Bond film “Quantum of Solace,” then beat his own record with a bang for the 2015 Bond film “Spectre.” There’s a photo of the “Quantum” bada-boom in the exhibit.

“Fabulous explosion,” Simmonds said, studying the image.

“Yes, I think so,” Corbould agreed.

He turned to me, “See, doing a Bond, they want as much real as possible. Most is not CGI. Bond is strapped to this table and there’s a drill about to go into his head but then he’s escaping and there’s all these gas pipes — oh, it’s massive — the explosion starts right here, just what you see in this picture, then it goes around and comes up to the two actors, who are in the foreground of the shot. There’s like 300 separate explosions in that shot, set off with computerized detonators, all set to go at a specific time. But … when you press the button, there’s a three-second delay, and so I say to Daniel Craig, I say, ‘look, no pressure, Daniel, I am going to press this button before you finish your line and so do not (expletive) that line.’ Months of work to set this up. On the other hand, you build in contingencies — so even if half the explosions don’t go off, it’s still big.”

Simmonds listened with the proud face of a stage parent, or rather, in this case, the steward of artifacts from a film franchise that dates back to the Kennedy administration.

“You know,” she said, “I think we had to leaflet Bedouin nomads who were nearby that explosion, to say, ‘OK, this is not the beginning of World War III, it’s just James Bond.’”

We walked on.

Among the first large pieces you see is an Aston Martin that flipped in “Casino Royale.” Actually, Simmonds notes, “it was flipped a record-breaking number of times — seven!”

As trashed as it looks in the MSI gallery — deep scratches along the body, caved-in windows and sunroof, demolished headlights — I’ve seen worse still driving on Lake Shore Drive. “The stunt men came to us,” Corbould said. “They tried to flip it without help but Aston Martins are not to made to flip, so we built into the car a little piston that the driver could spring with a button. It shoots down under the car, provides that little physics advantage, and you get what you see in the movie, a car going over and over.”

Simmonds said, “When I saw the footage, I thought to myself, now this is where Bond gets unreal for me. Nobody could survive that crash, yet Bond does. Thing is, the stunt driver, of course, did survive. I sat next to him at dinner the next day. He looked great.”

Corbould told me the only time he doubted if he could convincingly stage something was not for a Bond film, but while making “Dark Knight” in Chicago. He had to flip an eighteen-wheel truck on LaSalle Street. He pulled it off, with heart-stopping precision. He also conducted the explosion in that film that took down a former Brach’s candy factory on Cicero Avenue. He talks about this stuff with such British nonchalance, he made racing an Aston Martin across a frozen lake in “The Living Daylights” sound like a casual day. He waited three weeks for ice to get thick enough. He’s never lost a Bond car in a frozen lake yet. But he worries about how he would get one out if it happened.

Clearly, looking around, we have a gadget for that.

One of the niftier aspects of this nifty show is the number of actual spy knickknacks the MSI included, mostly on loan from the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C. KGB cameras, CIA surveillance recorders, flasks that smuggle papers, dagger-loaded soles. But it’s the Bond stuff that’s legit nuts. Dynamite toothpaste (“Dentonite”), escape sleds that act as cello cases. “Here is the Man With the Golden Gun’s golden gun!” Simmonds said. The barrel doubles as a pen, the trigger is a cufflink. It’s very gold and very gaudy.

I asked her if they call it the Trump Gun around the office.

“Hadn’t thought of that!”

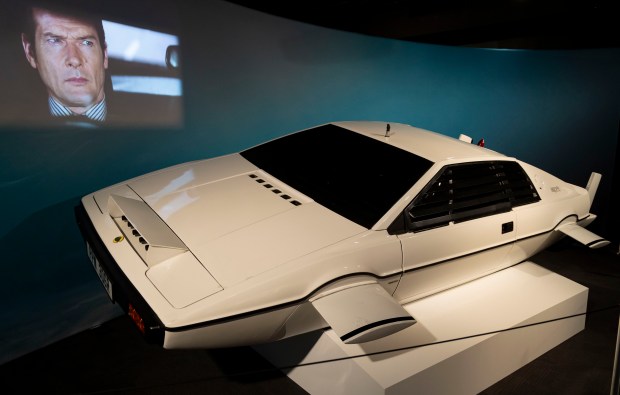

We passed a submarine car — “Elon Musk bought our motorized version at an auction,” Simmonds said. We passed an underwater breathing device that so impressed the Corps of Royal Engineers, they requested the blueprints from the filmmakers. (The art director told them it would only work if they held their breaths a long, long, long time …)

We stopped at a pair of jetpacks, one vintage, one contemporary.

Along with flying cars, the holy grail of long-prayed for technology.

“So this jet pack,” Simmonds said, nodding at the older model, an artifact of 1965’s “Thunderball,” “this jetpack never exactly lifted off. We could only store enough fuel for 21 seconds of flight.” She sighed like it was a personal failure. “I still want one though.”

“007 Science: Inventing the World of James Bond” runs through Oct. 27 as a timed-entry ticket at the Museum of Science and Industry Chicago, 57th St. and DuSable Lake Shore Drive; $18 plus museum admission, or $35 for special exhibition-only evening hours, at www.msichicago.org

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com