I am proud to be from Naperville. My grandparents moved there in the 1950s, my parents lived there for 50 years, and I spent the first 18 years of my life there.

I am now a professor in the Department of Genome Sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. To the extent that I’ve had a successful scientific career, I believe the education I received in Naperville public schools deserves a lot of credit. It was there that I first learned to be a scientist.

The last time I wrote something for the Naperville Sun was 42 years ago. I was in the eighth grade at Jefferson Junior High School and debating a local clergyman about the pros and cons of playing Dungeons & Dragons.

I am writing today to share my experience of the current attacks on higher education and scientific funding being carried out by our federal government.

First is the multipronged defunding of scientific research involving the National Institutes of Health, USAID, the National Science Foundation and other agencies.

I am trained as a computer scientist, but my research involves applying machine learning techniques to biological data. Think ChatGPT but for proteins and DNA. Essentially all of my research is funded by the NIH and the NSF. Why? Because no pharmaceutical or biotech company is interested in funding basic research.

To understand what I mean by “basic research,” let’s talk about what it takes to discover a new drug. A drug candidate must pass through a complex pipeline to validate the drug’s effectiveness, make sure it’s safe and rule out substantial side effects. But before that pipeline can begin, you have to come up with a candidate drug. Drugs essentially always involve interactions with proteins because they are the molecules that carry out most of the functions of the cell. How do we know which proteins to target with a drug, which ones might be involved in a given disease? Basic research.

For example, some of my research involves training deep learning methods to interpret mass spectrometry data. A mass spectrometer measures dozens of proteins per second, detecting and quantifying thousands of proteins in a single experiment. These types of measurements, collected from cohorts of patients with, for example, Alzheimer’s disease or cancer, can identify which proteins act differently in patients with and without the disease.

The problem is that the measurements themselves are useless unless someone develops software to help map the observations to the corresponding protein sequences. This is one thread of my research, which has been funded by the NIH and the NSF for nearly 20 years. This research does not lead directly to new drugs; it is a piece of the infrastructure that is needed to search for new drugs or to ask fundamental questions about human biology.

As another example, my colleague and collaborator, David Baker, won the Nobel Prize a few months ago for his research on designing novel proteins. A big component of that research involves applying machine learning techniques to protein sequences. Much of David’s research has been funded by the NIH but even more importantly, all of David’s research relies on a huge protein database, called the Protein Databank (PDB), that has been funded by the NIH for the last 50 years at a cost of over $100 million. This is the data that is used to train models to predict protein structure and to design novel proteins.

Indeed, the astonishingly fast development of mRNA vaccines against COVID19 is often credited to biotech companies like Moderna. But Moderna’s success would not have been possible without the PDB. Similar to the publicly funded Human Genome Project, which provided a backbone upon which to scaffold all of our knowledge about human genetics, the PDB is a critical piece of scientific infrastructure that never would have come into being without public funding.

The changes now being enacted in Washington, D.C., will hobble the NIH. The Trump administration will tell you that they are simply adjusting the “overhead” rates that universities and research institutes charge to the NIH, with the aim of bringing them into line with the flat 15% rate that is charged by some private foundations.

This is misleading because those foundations typically allow many charges to a grant that are disallowed by the NIH. For example, the administrators who fill out much of the paperwork required by the NIH have their salaries paid by overhead. In practice, overhead also helps to pay for things like the building I work in, the electricity and heat that power that building, and the custodial staff. Cutting overhead means that many research projects will be canceled and many academic staff will be laid off.

This attack on the NIH is part of a larger assault on higher education. The nominal aims of orders to, for example, stop anti-semitism or halt the teaching of diversity, equity and inclusion topics are smoke screens for an attempt to hobble institutions that are perceived to house a liberal elite.

Our higher education system is the envy of the rest of the world. I have mentored 63 PhD students and postdoctoral fellows, of which more than half came from another country to study in the United States. We should continue to support our system of higher education and its partnership with the NIH and other federal funding agencies, not destroy a system that has proven to be wildly successful.

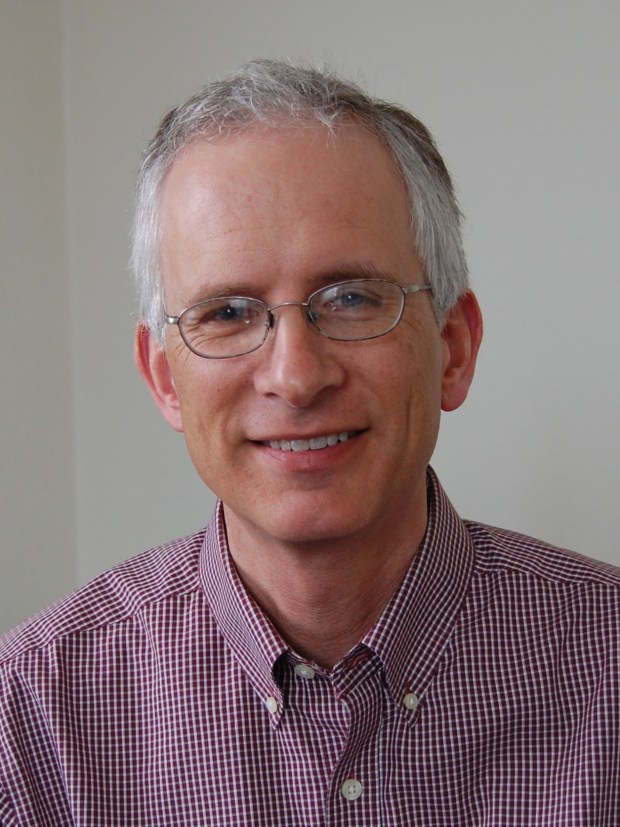

William Stafford Noble, formerly William Grundy, is a 1987 graduate of Naperville North High School. He is a professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle.