Preservationists are seeking an eleventh-hour reprieve for a historic 152-year-old River North building facing imminent demolition.

The three-and-a-half story brick and cast-iron building at 720 N. Wells St., which rose from the ashes of the Great Chicago Fire with the seventh permit issued during the city’s rebuilding, is set to fall to the wrecking ball within days for redevelopment.

“This is one of the first buildings in the River North community built after the Chicago Fire, sort of representing the city that burned,” said Ward Miller, executive director of Preservation Chicago. “It’s just tragic to see this come down. There’s so few of these buildings dating back to this period remaining.”

The building at the southwest corner of Wells and Superior streets, along with an adjacent but smaller Italianate building of similar vintage, are not designated Chicago landmarks. They are slated for demolition to make way for a four-story club designed by New York-based Robert A.M. Stern Architects that is planned for the site, according to the Chicago Planning Department.

The project’s developer, Liam Krehbiel, founder and CEO of Chicago-based Topography Hospitality, did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday.

The sturdy but ornate Wells Street corner building, which features brick above the ground floor cast iron columns and arches, is a monument to the city’s resilience in the wake of the 1871 Chicago Fire, which burned down a third of the nascent metropolis and obliterated the River North area.

The building was among the first to rise from the rubble.

Built in 1872 by Conrad Seipp, a German immigrant and prominent 19th century Chicago brewer, the first floor initially featured store fronts and the second floor housed offices. The lofty third floor was designed as a large Masonic Hall, and later repurposed as a Swedish social club.

Its modern history has also been colorful.

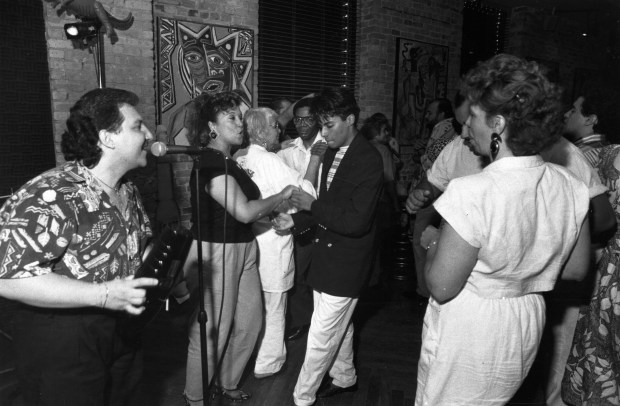

In 1988, the building was dramatically reimagined by acclaimed Chicago-based designer Jordan Mozer and reborn as the trendy Cairo nightclub, featuring a lower-level disco with coal shafts as seating nooks, a zigzag bar, gold walls and large pillows hanging from ceiling light fixtures.

More recently, it was repurposed for a post-millennium run as The Boarding House, the debut restaurant from Alpana Singh, the Chicago sommelier and longtime host of the popular WTTW-Ch.11 TV show, “Check, Please!”

The restaurant, which opened in December 2012, was hailed by Chicago Tribune food critic Phil Vettel as exuding “a friendly, relaxed charm on every level,” with a hearty menu, a top floor bi-level dining room and a dramatic wine glass/chandelier art installation. Not surprisingly, the restaurant also featured a “formidable” 500-bottle wine list, and plenty of interesting spaces to sip it.

Singh closed the restaurant in 2018, and the building has since become a vacant redevelopment target in the post-pandemic urban landscape, Miller said.

Despite its storied history, the building was never designated a Chicago landmark, which would prevent demolition.

It was also not included in Preservation Chicago’s annual most endangered buildings list, which was published March 6. But the group sprung into action when it subsequently learned of redevelopment plans, petitioning the Commission on Chicago Landmarks to grant it landmark status in a bid to stave off demolition.

That entreaty did not prove successful.

“Given 720 N. Wells’ age and in response to suggestions by the public, preservation staff researched the building and determined it does not present a strong case for meeting landmark criteria,” a Landmarks Commission spokesperson said Wednesday.

Preservation Chicago has long sought broader protection for a proposed River North Landmark District, which has been “sitting on a shelf” at City Hall for 15 years, according to Miller. The city said the proposal, which never moved forward, did not encompass the Wells Street building.

While Miller hopes for a last-minute stay of demolition, he said the building might serve as a “canary in the coalmine,” prompting Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration to reconsider implementing an expanded preservation proposal for River North.

He would also like to see Chicago adopt a rule requiring a demolition review for any building over 50 years old, similar to regulations in Boston and other cities.

Fencing has already gone up around the 720 N. Wells St. building and the adjacent three-story building at 207 W. Superior St., which was listed as an orange-rated potential landmark on the nearly 30-year-old Chicago Historic Resources Survey, but subsequently did not meet the criteria for historic designation.

When the developer applied for a demolition permit in May 2023 for the 207 W. Superior St. building, it was put on hold for 90 days and then approved for removal in August. As a green-rated building, the 720 N. Wells St. building didn’t require such a review before seeking demolition, the city said.

“The survey missed the most historically significant structure on the block,” Miller said of the Wells Street building. “Time and time again it slipped through the cracks. Now it may be too late for this building, but I hope it will lead to a broader landmark district for River North.”

rchannick@chicagotribune.com