Robin Moore initially had one purpose: learn more about the life of her grandfather Reginald Moore. She remembered him as a very loving and hardworking person, but details surrounding his early life remained a family mystery — one that she was determined to uncover.

She never expected that mission to take her to a grassy field in a remote part of Canada, where several of her ancestors are buried.

Since 2018, Moore — a native of Park Manor on Chicago’s South Side — has spent much of her free time combing through archival records and building a family tree to better understand her roots. The genealogical project has taken her all the way to a cemetery in a small town in Canada, located about two hours west of Toronto.

“The Canadian heritage has always been known,” Moore said, noting that her father’s parents were born in Canada and that she frequently visits the Maple Leaf Country. Now that she’s older and started paying attention more to her family history, Moore has gotten in touch with all different kinds of people — genealogists, historians, archeologists — which eventually led her to learn about the town of Ingersoll, Ontario, and the early Black settlers who lived there.

“I’ve run into a million projects that were being done throughout Ontario, so it started to maybe not even reshape but shape my understanding of these early settlers,” Moore said. “These early families that came up there, where they lived, how they moved about, what they may have had to experience where they lived, how they connected with one another.”

Since the 1960s, tracing family lineage has grown among Black Americans, according to Jane Rhodes, a Black studies professor at University of Illinois Chicago. While many Black Americans knew their family history through oral histories passed down over the generations, digging into and embracing that history was not as common. Many families, Rhodes explained, were scared to dig into that history since it meant confronting America’s history with slavery.

But the emergence of the Civil Rights Movement and Black pride taught people that they should embrace that history, which led to the emergence of more Black families conducting genealogy. “In the last 25 years, you really see people develop as genealogists as a profession and black genealogy being a particular subspecialty,” Rhodes said.

Some of Moore’s ancestors, she would learn, are buried in a potter’s field in Ingersoll Rural Cemetery — a grassy, unmarked plot of land in the far back corner of the cemetery allocated for those who did not have the economic means to bury themselves. At least two ancestors — Moore’s great-great-grandfather James Hisson and his wife, Anne — came to Canada through the Underground Railroad.

Around 400 people are buried in that field, according to Cody Groat, an assistant professor at Western University who is from Ingersoll and studies the potter’s field. Among those buried include Black people fleeing slavery, British Home Children (poor, orphaned British children who were shipped to places like Canada to work as indentured servants) and Chinese immigrants who came to Ingersoll to avoid the Chinese Head Tax, a large fee Chinese migrants had to pay while emigrating to Canada.

“So there’s a lot of these grand narratives of Canadian history represented in the potter’s field,” Groat said. “Slavery, Chinese Head Tax, British Home Children — all of these grand narratives of Canadian history can be told through this very localized, regionalized potters field.”

Moore’s story is one that fits in with those early Black settlers in Canada. It was a story she shared with over a dozen people at the Consulate General of Canada in Chicago on Feb. 12 for Black History Month.

Itinerary: A weekend trip to sites on Illinois’ Underground Railroad

Many of the settlers in Ingersoll were already free by the time they arrived, according to historian George Emery, who has written extensively about the topic. Groat did note, however, that some of the settlers buried in the potter’s field were former slaves from the U.S.

“It was … a little larger than what I thought it would be, especially when I look back at it now,” Moore said. “But when I was in it, I didn’t know what was ahead. And so it was just like I was just doing the next step — someone would call me, they tell me information, I’d write it down, and then I’d go to the next step.”

The journey to Ingersoll

It was early last year when Moore decided that she was going to use all the information she gathered to put together a family tree.

“Putting together a family tree was actually something that I did not want to do. I had never wanted to do it,” Moore said. “I’ve seen very extensive family trees. I think they’re awesome, but they just seemed like a lot of work.”

But Moore still had lingering questions about her family members and a tree could help answer some of those outstanding questions.

As Moore worked on a section about her great-great-grandfather on her grandmother father’s side of the family, she realized that she hit a wall.

“I could follow him in Canada, in Ontario, I could follow him all up until a certain point and then I didn’t see him anymore,” Moore said. “At some point, I saw his wife, she was a widow. So I knew he had died, and I could pretty much figure out the time frame in which he died, but I had no information on where.”

Illinois’ Underground Railroad: Stories of escaping enslavement

After asking friends in Canada and searching through Ancestry.com, she learned of a gravesite in a small town called Ingersoll. Moore was previously aware that she had a family connection to the town but wanted to learn more, so she called up the cemetery in Ingersoll and was eventually connected with Groat.

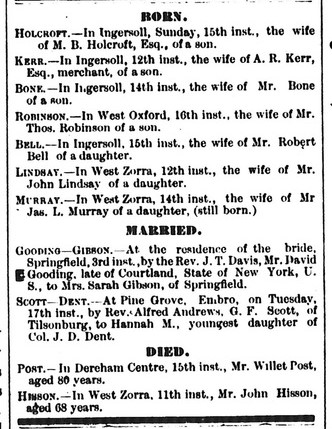

Groat and his graduate students found an old newspaper death notice for James Hisson, who was believed to be Moore’s great-great-grandfather. Moore was planning a trip to Ontario to visit relatives last July and decided to use the opportunity to visit Ingersoll. She met up with Groat, who showed her the potter’s field in the far back corner of the cemetery.

The population of early Black settlers in Ingersoll and surrounding towns was the most prominent in the 1850s through the 1880s, when Ingersoll’s growth started to stall. The most dramatic decline, according to Groat, was around the 1920s, near the same time the Ku Klux Klan became more active in the area. Those who came to Ingersoll to establish a new life for themselves pursued jobs as laborers, barbers and waiters, among other professions. There were also Black churches that served as an important gathering spot for the Black population.

While life in Canada for Black Americans meant freedom, it was not easy. Many Black Americans came to Canada with little resources and faced frequent discrimination. In Ingersoll, white residents often looked down upon the Black residents, attended shows that portrayed negative stereotypes of Black people and sometimes even got into clashes with the Black residents, according to Emery.

The potter’s field in Ingersoll was active from 1864 and 1976, and many Black Canadians are represented in the potter’s field.

“Now, if you’re standing in the potter’s field, and he says, ‘Robin, there are 400 people buried here,’ you’re going to do what I did and you’re going to say, ‘No, there are not,’” Moore said. “It is so small I can’t even imagine that there would be 200 people buried there, let alone 400.”

It is believed that the people buried in the potter’s field are stacked on top of each other, Groat explained. There are only about five markers above ground in the field, and prior to Groat’s research, many people in Ingersoll did not even know that there was a potter’s field there.

“This cemetery is walked through all the time. There’s people who walk their dogs, strollers,” Groat said.

Thanks to special noninvasive technology, Groat and his team are able to detect any people or artifacts buried in the field. While Moore could not find a marker for Hisson, Groat did show her some records that confirmed for her that she was in fact related to this man buried in the field in 1874. Moore later confirmed that Hisson came to Canada through the Underground Railroad, but beyond that, not much else is known about him.

At one point when working in the field, Groat and his team discovered an object buried underground. Archeologists dug and found two headstones located close to each other, one of which was for a girl named Arvella Henderson — who died when she was less than a year old.

“Crazy enough, as he started describing that headstone and telling me about that person, I kind of had to stop him, because it was very shocking to me that this was a person that I knew,” Moore said. “It wasn’t the person that I came there for, but it was a person. It was a family that I knew.”

Arvella was not the only Henderson buried in that field. That family, Groat said, represented an important aspect of the potter’s field: This is a burial plot where generations of families were laid to rest.

“It was just kind of moving for us to piece together, like, Robin could picture her ancestors burying young Arvella Henderson,” Groat said.

Why it matters

For Moore, this project has led to her not only better understanding her past, but also more about world history and how she fits into that history.

“They came to Ontario because they wanted to have a better life. They wanted to have a freer life,” Moore said. “This year I’m learning about them, learning that they came over and these things that they did and these things that they went through. I think it was for the betterment of generations to come.”

And now, Moore gets to share this information with her family, for generations to come.

“To actually search for the truth and leave that for myself and my kids, that’s special,” Andrew Harris, Moore’s son, said. “Finding out about ordinary people that made extraordinary decisions — I wanna tell that story.”