Human remains were found inside a car pulled Tuesday from the Fox River that belonged to Karen Schepers, an Elgin woman who has been missing for nearly 42 years.

Elgin Police Chief Ana Lalley made the announcement in a Facebook post Tuesday night.

“At this time, the Kane County Coroner’s Office has confirmed through a forensic pathologist the presence of skeletal human remains that were located inside the vehicle,” the post said. “The next steps will be to compare DNA samples or dental records of Karen to the remains located in the vehicle to confirm a positive identification of the remains that were found.”

The identification process could take several weeks, Lalley said.

Schepers’ car was discovered late Monday afternoon by Elgin police and a dive team, which had spent the day searching locations where her car might have gone into the water on April 16, 1983, when she was last seen leaving a Carpentersville bar and was believed to be driving home to her Elgin apartment.

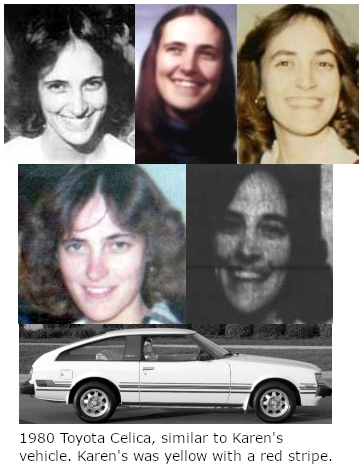

Crews were able to remove the vehicle — a canary yellow Toyota Celica hatchback with an orange stripe and a license plate number matching the one that had been on Schepers’ car — Tuesday afternoon but no confirmation on what was found inside was immediately released.

The search was part of an investigation undertaken by the Elgin Police Department’s Cold Case Unit, which produced a podcast, “Somebody Knows Something,” in an effort to put a new light on the missing person case, which went unsolved for four decades.

Covered in mud and branches, the car was discovered in about 7 feet of water by Chaos Divers, a nonprofit that specializes in finding missing people in bodies of water.

Working with Elgin police detectives Andrew Houghton and Matt Vartanian, the team spent the day Monday systematically searching the river in hopes of locating the vehicle.

Chaos Divers manager Lindsay Bussick, who was joined in the search by company owner Jacob Grubbs and diver Mike McFerron, said Monday they initially focused on areas of the river that run alongside Duncan Avenue, one of two routes Schepers would have likely followed to get home.

“There are so many spots where it is so close to the river,” Bussick said.

The crew uses three types of sonars, including one with a scope that provides a live feed that’s almost like an ultrasound, she said. “There are times we can get such a clear image where we can almost tell what make and model the vehicle is.”

However, that wouldn’t have been the case here, she said. “… with her being missing for so long, we are kind of looking at it differently,” she said. “We are looking for shadows because we have to take into account deterioration and that kind of thing from just being in the water and the flow of the water over that vehicle.”

Police have long believed that one explanation for Schepers’ disappearance could be that she drove into a body of water, which would explain why her car was never found, her credit cards and bank accounts left untouched, and nothing from her apartment taken.

According to the podcast, Schepers was born in San Francisco, the second of nine children. The family moved to Sycamore in 1965, and she graduated from Sycamore High School in 1977.

She later moved to Elgin, where she worked as a computer programmer for First Chicago Bank Card. She had been dating a man named Terry Wayne Schultz, but they’d broken up several weeks earlier after being unofficially engaged, police said.

On the night of Friday, April 15, Schepers joined about 20 coworkers at P.M. Bentley’s, a now-closed Carpentersville bar, to celebrate the completion of a work project. She talked to Schultz that night, but he opted not to meet her at the bar, police said.

Schepers was last by friends and witnesses participating in a hula hoop contest. She left the bar in the early morning hours of Saturday, April 16.

When Schultz failed to hear from her later and she didn’t show up for work on Monday, he notified police that she was missing.

Schepers’ 90-year-old mother, Liz Paulson, was among the family members interviewed for the podcast. The family feels like it’s hard to move forward until “you fix this,” she said.

Paulson still lives in the family’s Sycamore home, which looks the same as it did in 1983. It has never been painted a different color so Karen would recognize it if she ever returned, said her brother, Gary Scheppers. In the interview, he said he still held a sliver of hope that he would see her again.

“Mom and I are still in the house. We are waiting for her to show up one day,” Gary said. “I would be surprised but I wouldn’t be surprised if that happened.”

In the podcast, Houghton and Vartanian outlined the reasons why it was important to look at the river and other bodies of water. Chief among them were the weather conditions when she left the bar and the river’s high water level at the time, they said.

There were two routes Schepers could’ve taken to return to her apartment in the 300 block of Lovell Street on Elgin’s east side, the detectives said. Duncan Avenue would have been the more common route, they said, although she also could have taken Route 25.

The two detectives researched the phases of the moon to determine how dark the road would have been and learned there was a crescent moon that night in which only 10% was illuminated.

“It would’ve been pretty dark,” Houghton said in the podcast.

There also would have been less light pollution because Elgin’s population was only about 60,000 and the town not as built up as it is now, he said.

Temperatures were below freezing and there were gusting winds, data show.

Additionally, the Fox River was at a record high level that week, much higher than the normal 8 feet it would have been along that stretch of road, the detectives said.

Water or ice on the roadway could’ve caused Schepers’ car to slip or crash and, if it did, her response time might have been affected by any alcoholic drinks she’d had at the bar, they said. If she was incapacitated by a crash, her car could’ve veered into the river.

Houghton and Vartanian said they planned to explore other theories, such as whether Schepers might have decided to leave Elgin, may have intentionally hurt herself or encountered someone who did her harm, if the search proved fruitless.

“It’s important we exhaust all investigative methods . . . because there are always going to be questions,” Lalley said. “The purpose of the Cold Case Unit is to find answers and, more importantly, bring some peace and closure to the family, if we can.”

Being part of a mission to locate a family’s missing loved one can be “incredibly rewarding,” Bussick said.

“It’s heartbreaking at times because when we do locate someone, you are taking that hope away from them that their loved one may pull back into the driveway,” she said. “At the same time, you can watch this weight be lifted off them.”

To listen to the podcast, click here.

Gloria Casas is a freelance reporter for The Courier-News.