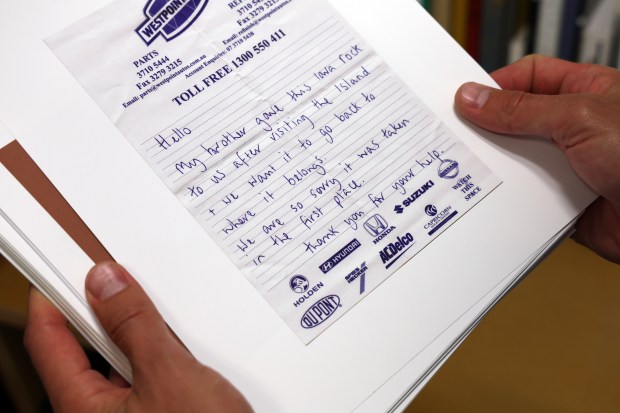

A few years ago, on Washington Island, in Door County, Wisconsin, the police department received a cardboard box. Inside was a note on blue paper that read: “Please return to Schoolhouse Beach.” The box contained three smooth grayish-white rocks, exactly the kind tourists routinely take from Schoolhouse Beach, touted by locals here as one of best beaches in the world composed entirely of stones. If you are caught taking even one of those rocks, you could receive a $250 fine. Presumably, whoever mailed these rocks — there was no return address or signature on the letter — faced $750 in fines.

And yet the simple fact that someone took time to return three rocks that look just like every other rock on Schoolhouse Beach suggested a more existential concern was nagging.

Their conscience spoke to them.

They felt guilty, perhaps worse.

That’s why Ryan Thompson, a 43-year-old Forest Park art professor, has made the study of such acts a specialty. He thinks of them as “conscience letters,” small acts at grace, and in the past decade he’s assembled two art books showcasing the correspondence and the stones, sand, bark and more that tourists have mailed back to national parks. He sees these letters not just born of remorse and fear but as, in a subtle way, small nods to the impermanence of man, tiny recognitions that nature continues on long after the modern world passes through.

“Some people who write these letters say stuff like ‘This was so beautiful, I couldn’t help myself, I needed a memento,’ which is kind and honest. Maybe they’re trying to use this rock or whatever to connect themselves to a favorite place, long after a trip — it’s what souvenirs do. But the irony is they also sit on shelves, get forgotten, then fail at that job.”

Summer vacations are winding down. Maybe it’s time to own up to your own environmental larceny? Hmmm?

As anyone who works at a state or national park, or even a local garden, can attest: Happens all the time. Visitors remove pieces of the very landscape that brought them there, leaving less of that landscape for everyone else, even if it’s one less pebble.

“People will help themselves,” said Kim Shearer, curator of collections at the Morton Arboretum. “They dig up plants, perennials, make cuttings, gather wood. I know (another garden) where a visitor removed an entire tree for Christmas.” At Indiana Dunes National Park, visitors take wildflowers, pinecones, rocks, and the park is aware because occasionally its offices get a package of dead flowers or pinecones or rocks with notes of apology. “Usually from children, and you can tell a parent made them write it,” said executive assistant Dena Mourtos. “Mostly, people are respectful. But I bet many don’t know you shouldn’t take anything from a national park. If everyone took a pinecone, wildflower or rock — we get millions of visitors a year — it adds up.”

Depending on the park, visitors also take quartz, shells, cactus, animal skulls …

Many, many things, both natural and indigenous to its environment, will walk out the door. Chicago Botanic Garden has posted signs in recent years asking visitors not to take fruit and vegetables out of its gardens. (The produce gets harvested and donated to the Roberti Community House in Waukegan.) Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania once got a bag of its battlefield dirt, with a note of apology to its ghosts.

There’s an old adage: “Take nothing but photos. Leave nothing but footprints.”

As Thompson’s work illustrates — a lot of people want a little more.

His first book of conscience letters, cheekily titled “Bad Luck, Hot Rocks,” was a poignant cataloging of personal angst and acts of repentance. Everything in it was either mailed back to or returned by someone who visited the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. The park has a large cache of such letters, including one from 1934 that reads: “I was going to make a necklace out of this, but it would have been a millstone around my neck.”

They also have a letter from a woman named Donna returning the glittery fossil her mother-in-law pilfered 40 years earlier. Another package described its returned goods as “a ton of bricks on my conscience.” A letter from 1964 says: “If you think I should pay a fine or go to prison, I am at your mercy.” A letter from 1970, in the large block letters of an elementary school student, reads: “I am only 5 years old and made a bad mistake.” A letter from 2014 offers: “I felt quite the rebel picking these up and putting them in my pocket, but hindsight is a wonderful thing.” Some people note a string of bad luck that followed their theft, describing lives that spiraled downward.

One asks to be “absolved.”

If you’ve never been, the Petrified Forest is vast and unique. You can see why so many would be enticed to fall from grace: It is 150,000 acres of ancient trees dating to the Late Triassic period, 200 million years ago. Slowly that wood and bark fossilized, becoming a rainbow of minerals scattered across the Arizona landscape. The park says literal tons of its namesake attraction are removed every year by tourists. So much so that park signs, for decades, reminded visitors the fossils were said to be part of a curse and never to be disturbed. The thing is, studies at the park later suggested that these signs seemed to be daring people to remove more fossils.

Leading to more conscience letters.

At Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Thompson, 43, teaches art, photography and the links between art and ecology. But since studying geology in graduate school at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, one theme of his life has been mankind’s strange relationship with the natural world — particularly geology. He says he began to think about time in philosophical ways, in eon-spanning ways. He became interested in the value we place on certain natural objects and not others. He studied glacial erratics, often large boulders deposited in odd places during the last ice age. He looked at how people form beliefs around crystals. He visited Arizona State University, which has a large collection of meteorites, to study its less-popular holding of “meteorwrongs,” terrestrial rocks mistakenly believed by their donors to be meteorites.

He was also thinking a lot about superstition when, while visiting those meteorwrongs, he heard about the Petrified Forest’s collection of letters pleading for forgiveness. Its park rangers handed him a binder containing thousands of such letters, spanning 90 years.

“I was blown away at how many blamed their problems on taking an inanimate object. People blamed the death of parents and pets. One person said they had a heart attack they were so worried about being caught with their rock. But I’m also not permitted to say these people are nuts. I grew up believing in God, and I still call myself a Christian, so I have a set of beliefs that I can’t prove. You subscribe to something, and that’s faith.”

The Petrified Forest led to another mountain of conscience letters collected by rangers at Haleakala National Park and Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park in Hawaii. His latest book, “Ah Ah,” takes its name from the phonetic pronunciation of types of lava flows. It includes images of jars of sand and volcanic rock mailed back, with more letters of shame. Many are addressed to Pele, a Hawaiian volcano deity. One letter asks: “Please put back in volcano. Thanks.” Another was written on a medication pad. One visitor returned the Nikes she wore to Kilauea volcano, concerned that specks of lava dust have been stuck to the soles, bringing bad luck with her everywhere she goes.

Generally, it is illegal to knowingly remove any objects from a state or national park, human-made or otherwise, regardless of how small or seemingly insignificant. How rigorously parks enforce this varies. But a mountain of laws apply: preservation laws, archeological protection laws, antiquities acts. Last spring, Canyonlands National Park in Utah released images of two visitors who allegedly removed artifacts from a historic cowboy camp in the park. The pocketing of national park objects has been a concern since the late 1950s when Fossil Cycad National Monument in South Dakota was so stripped of fossils by tourists that the park lost its monument status.

But there’s also the irony, in many instances, of objects returned to land that’s considered by Native American and Indigenous people as stolen itself. Thompson notes how taking volcanic rock, for instance, is a result of tourism — itself, a byproduct of colonization. He thinks of visitors returning volcanic rocks as an informal act of repatriation, echoing somewhat how museums face stronger federal regulations that require the return of sacred artifacts to Indigenous tribes. His next project concerns conscience letters received by Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico, where fragments of Pueblo pottery found on its land are routinely taken by tourists.

In fact, not long ago, at Dickson Mounds State Museum in central Illinois, an ancestral necklace was left by an anonymous visitor to the Native American settlement. Older staff soon recognized that the necklace had been missing from an excavated part of the grounds since 1973. Alan Harn, curator emeritus of anthropology at Dickson, said it was the only time Dickson’s ever seen anything returned — unless you count that time they found a box of skeletal remains, presumably of Native Americans, presumably Indigenous to central Illinois, left at the back door.

The majority of conscience letters or acts of conscience, though, come with an apology.

Some acknowledge the ways in which a natural environment is codependent on every bit of itself. But most just feel bad. Gary Schultz, Washington Island’s only police officer, chuckled: “We get these a couple times a year, but usually just a box of rocks, no letter.”

Most of these good deeds, however, are dead ends.

Parks that receive previously stolen objects often don’t know what to do with them but leave them in a box in the corner of an office; to toss them back into a natural environment would be to change again what a supposedly natural place looks like. But the act itself is encouraging. At Indiana Dunes, Dena Mourtos always writes back a thanks-for-being-honest letter, and if a child returned the objects, she includes a Junior Ranger Activity Book. To Thompson, the letters are touching and hopeful. “These are people coming to terms with a decision made last week or 30 years ago. They’re fundamentally redemptive acts. So much is wrong in the world because people dig in and can not find it in themselves to admit when they’re wrong, and the only thing these letters have in common are that the writers are trying to fix their mistake in a small way.”

Some use a conscience letter to stare into the hand of fate and accept their chances: “By the time these rocks reach you, things should be back to normal. If not, I give up.”

And some just need to be heard: “I was so excited that I could be a part of something that took place millions of years ago. … I hope you can forgive me. … Please forgive me.”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com