Illinois House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch’s office issued an order instructing his 78-member Democratic supermajority not to speak to a Chicago Tribune reporter about “political matters” at the State Capitol or elsewhere, citing highly dubious grounds that such discussions could be an ethical breach.

One former veteran statehouse journalist described the order as a “goofy” and “stupid” attempt to try to stifle legitimate news-gathering activities, while the head of the state’s press association said reporter conversations with lawmakers about politics are legal “constitutionally protected” free speech.

The order was issued Thursday after Welch’s team apparently became irked by questions being asked of the speaker’s leadership team by Tribune reporter Jeremy Gorner about tens of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions that they made in support of Michael Crawford’s candidacy for an Illinois House seat in Tuesday’s primary. Crawford was the successful Welch-backed primary challenger to longtime Democratic state Rep. Mary Flowers of Chicago, the longest serving Black House member.

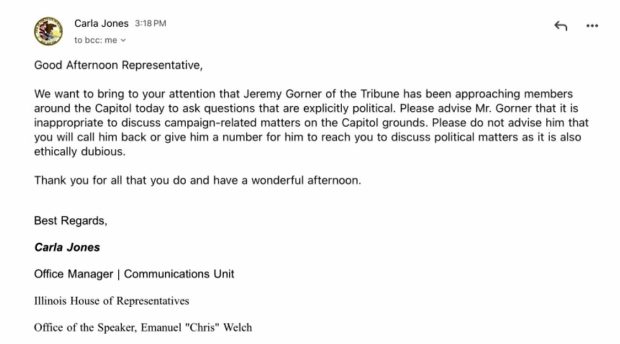

In a memo distributed in a blast email to House Democrats on Thursday afternoon, the lawmakers were instructed that they should not respond to Gorner’s questions nor should they “call him back or give him a number for him to reach you to discuss political matters as it is also ethically dubious.”

The memo warned that Gorner was asking questions “that were explicitly political” and stated that “it is inappropriate to discuss campaign related matters on the Capitol grounds.”

The memo was signed by Carla Jones, who identified herself as office manager in the communications unit of the “Office of the Speaker, Emanuel ‘Chris’ Welch.”

When contacted by Gorner about the memo, Jaclyn Driscoll, a former statehouse reporter who became Welch’s chief spokesperson in April 2021, falsely accused Gorner of questioning only Black lawmakers about Welch’s efforts to defeat Flowers. Gorner informed Driscoll that she was wrong and that he spoke to a variety of lawmakers who contributed campaign funds to Flowers’ opponent, regardless of their racial or ethnic background. Welch is the state’s first Black House speaker.

Contacted by another Tribune reporter, Driscoll said the memo represented “long-standing” policy. Informed that no such policy has existed in the statehouse for at least four previous decades, she was asked to have the House Democrats’ legal counsel provide statutory citations that prohibit political discussions by legislators on or off Capitol grounds.

None were provided because no such statutory prohibitions exist in Illinois law and, if they did, they would likely be in violation of First Amendment free speech protections.

The only statutory campaign prohibitions prevent lawmakers from being offered or accepting campaign contributions inside the Capitol and a ban on lawmakers and legislative candidates from holding campaign fundraisers on session days in Sangamon County, where Springfield and the Illinois State Capitol are located.

On Friday, Driscoll released a statement to the Tribune about the memo saying it was “overly cautious and was not prepared or reviewed by the House Ethics Officer.” She also said that at a meeting with lawmakers on Friday morning that the speaker’s office “clarified to members that nothing precludes them from answering reporter questions.”

Asked for documentation of the clarification, Driscoll did not provide any. She also declined to identify the people who put together the initial memo, but said Welch was not involved.

“I’m not going to throw staff under the bus,” she said.

She also did not offer an apology to Gorner or the media over the content of the memo, nor to members of the Democratic caucus for not trusting them to use their own judgment.

Asked about issuing an apology, after a long pause, Driscoll said, “I don’t see how this is beneficial.”

Tribune Executive Editor Mitch Pugh said, “we are disappointed in Speaker Welch and his office.”

“Clearly, this wrong-headed memo was an attempt to stifle our reporter’s constitutional right to do his job,” Pugh said. “We continue to support our journalists’ ability to ask elected officials tough questions, no matter the setting. We are confident our readers and Speaker Welch’s constituents expect nothing less.”

Virtually everything that happens at the State Capitol is rooted in politics.

There’s distinct seating of Democrats and Republicans on opposite sides of the House and Senate floors. There are meetings the two chambers’ four partisan caucuses hold behind closed doors to develop a legislative game plan. And there’s the drawing of gerrymandered district maps after the federal census, which each party has used to gain or keep power over the decades.

Perhaps the least political activity at the statehouse is the awarding of legislative license plates — senators by their district number and House members by their seniority.

Don Craven, president of the Illinois Press Association and its general legal counsel, said he knew of “no limitation of the ability of lawmakers to discuss election results, even in the Capitol.”

“Discussing election results (is) constitutionally protected activity and can occur anywhere,” Craven said.

Charles Wheeler, a former longtime statehouse reporter, called the policy stated in the memo “absolutely goofy,” recounting that at least half the time “if not more” of his quarter-century working in the Capitol involved asking questions that had to do with politics.

“It’s so stupid from a public relations point of view,” said Wheeler, an emeritus professor of journalism who is a past director of the Public Affairs Reporting Program at the University of Illinois at Springfield. “I just find it difficult to believe that a legislative leader would authorize one of his staff to tell his members not to talk to reporters.”

Wheeler also said the success of such an order was unlikely because independently elected lawmakers will not pay attention to it, although some interviewed by Gorner on Thursday declined to speak to him, saying they didn’t want to discuss anything campaign-related in the Capitol.

Welch’s memo to lawmakers came after the speaker, Democratic leadership and about a dozen unions bankrolled Crawford’s campaign fund against Flowers. State campaign records show more than a dozen House Democrats contributed to Crawford’s campaign, including top-ranking members of the Democratic caucus.

State Rep. Kelly Burke’s campaign contributed $10,000 to Crawford, because Welch “had asked me to donate,” Burke said.

“I’m a member of his leadership team,” said Burke, a Democrat from Evergreen Park who serves as an assistant majority leader in the House. “I’m happy to support the speaker when he needs my help.”

Records show that none of the more than $1.6 million that Crawford raised in large donations came from within the House 31st District he will represent if he wins the general election in November.

In an interview Friday with the Tribune, Flowers said she felt like Welch targeted her for speaking up at times against his leadership and that Welch’s backing of Crawford allowed him to not be forced to answer tough questions about what kind of lawmaker he’d be.

“He didn’t have to show his hands too much, but now he’s been exposed. But the damage is done to me and my constituents,” she said of Welch.

A spokesperson for Crawford didn’t return a request for comment. Crawford’s campaign repeatedly declined requests for comment to the Tribune throughout the campaign and after his victory.

Another assistant House majority leader, state Rep. Aaron Ortiz, said his campaign’s $10,000 contribution to Crawford stemmed from there being “a unified effort” among Democrats. The Chicago Democrat also said there were some things Flowers said that were disrespectful.

“As a leadership team, we all signed like a pledge to abide by these rules of respect and engagement and listening,” Ortiz also said, “and that’s something unfortunately that she kind of just tossed out the window.”

Flowers was pushed out of Democratic leadership last year after it was alleged that she repeatedly engaged in inappropriate behavior that included saying a Democratic staffer looked like Adolf Hitler. She acknowledged making the comment but said it was just one of a series of disagreements with Welch.

“They said I talk mean,” Flowers said of some state representatives who fundraised against her. “You know, I — yeah. I’m a little older than you, I’ve seen a little bit more in life. And I’m not an angry Black woman, but I do get angry when I see injustice done. And I have seen more injustice done than they have.”

Longtime political consultant Delmarie Cobb worked on Flowers’ campaign in its final weeks. She said the challenge to Flowers sends a concerning message to other legislators, particularly Black women.

“It sends a message that, ‘You’re next if I don’t like you,’ or ‘I can primary you too,’” Cobb said.

Flowers, the nearly four-decade veteran lawmaker first elected to the office when Harold Washington was mayor of Chicago, said she long prioritized services to Black mothers, infants and children, including those in the care of the state.

On Friday, Flowers said her only regret was being unable to continue serving her community, “my extended family.”