It sounds like something you wouldn’t believe unless James Earl Jones said it himself in a voiceover. But it’s true: Millions of us have spent uncountable hours of our lives – gratefully – with the sound of Jones’ voice inside our heads.

Today, we are all Luke, and he is our father, because the farm boy born in Arkabutla, Mississippi, later raised by his grandparents on a farm near Wellston, Michigan, is the one who said “I am your father.” He said it like he meant it, and we believed it in our bones, because that’s where Jones’ voice rattled and purred as Darth Vader in “The Empire Strikes Back” and other “Star Wars” pictures.

Jones, who died Sept. 9 at the age of 93 at his home in Dutchess County, New York, took on Shakespeare, the Greeks, Jean Genet and a hundred comedies, yet it’s the voiceover work that everyone’s talking about today. He is, after all, the man who said “This is CNN” and CNN was instantly and for decades classier, more distinguished for it. Another hundred or thousand or million people will hear his voice once again, or maybe for the first time, as Mustafa in “The Lion King.”

There were, of course, a few other things for which James Earl Jones will be remembered.

The beauty-of-baseball monologue, for example. The one about a vision of a spectral Iowa baseball diamond, in a field of dreams. The people will come, and it’ll be enough to make fans of the game, and of impossible yet possible father-and-son reunions over a game of catch, believe they’ve “dipped themselves in magic waters.”

As the reclusive novelist in “Field of Dreams,” Jones tossed off a pretty sanctimonious chunk of monologue so beautifully, that skeptics could only assume that Jones’ voice had been dipped in the same.

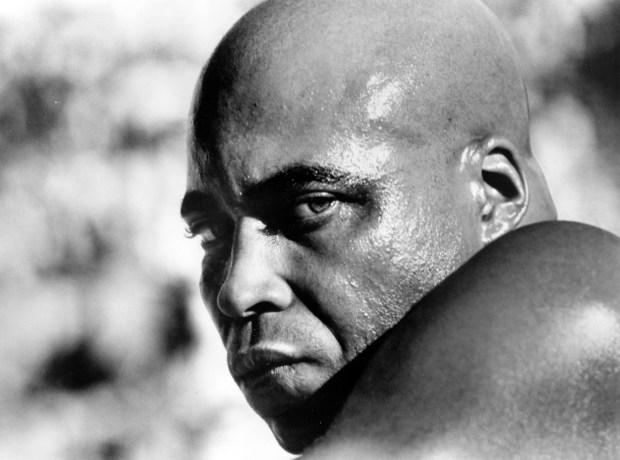

The voice was just the first thing you noticed with this actor.

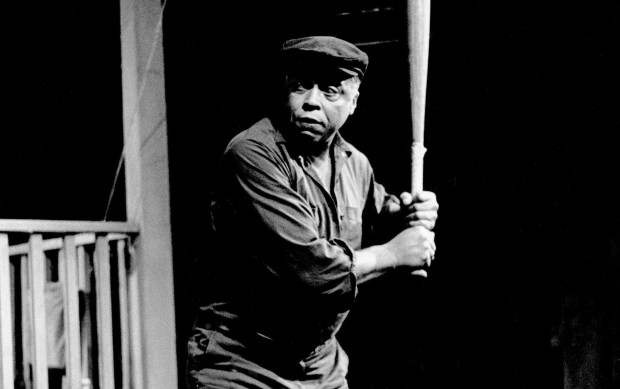

In Chicago, people still talk about the Goodman Theatre pre-Broadway run of “Fences” by August Wilson, a different, tougher-minded story involving baseball. Jones played Troy Maxson, a Negro League slugger robbed of his future because he came along too early for white America, before Jackie Robinson, to conceive of a future for any Black man in the major leagues.

Jones won his second Tony Award for that fruitful if troubled project; his first came for “The Great White Hope,” in 1969, as a fictionalized version of boxer Jack Johnson.

Critic Patti Hartigan’s recent August Wilson biography reveals the full extent of what happened with “Fences,” its battles over rewrites and struggles for artistic control between Wilson, the director and uncredited dramaturg Lloyd Richards (eventually fired from the project before returning and winning a Tony himself) and producer Carole Shorenstein Hays, Jones’ ally and confidant.

Speaking to Hartigan years later, Jones acknowledged the bad blood running every which way backstage, for months prior to the triumphant Broadway premiere in 1987.

“I hadn’t had anything to challenge me since ‘The Great White Hope,’ Jones told her. But Troy Maxson’s self-inflicted downfall in “Fences,” he added, made playing him a difficult, often dispiriting experience, never mind the backstage struggles during which Jones took over as director for a while, as he put it to Hartigan, “until the lawyers worked it out.”

Jones said this, too: “Fences” demanded his best, so that the character could live and breathe on stage in all his contradictions and qualities. To activate Troy and the play’s “frightening human aspect of heroism,” he said, called for everything he had to bear: violence, tenderness, a lust for life, hallucinatory square-offs with death. The performance filled the play, and Jones’ physical presence seemed to magically change size as the drama progressed, huge and vital one scene, frightened yet defiant the next.

Earlier in the 1980s, he toured with Christopher Plummer in “Othello.” In that production, Jones and Plummer appeared to be on the verge of violence between performers as well as between Shakespeare’s characters. Plummer’s fiendishly manipulative Iago big-footed every single moment they shared on stage together. Yet this duel of actors worked; it felt alive, and dangerous, even in a routine staging.

Most of us got to know Jones through television and especially the movies, whether we were into soaps (he was a pathbreaking regular on “As the World Turns” when Black performers had little reason to be encouraged, employment-wise) or “Roots.” Jones played Alex Haley in “Roots: The Next Generations,” but by that time, he’d won hordes of admirers for his raucous, joyous turns on screen in, among others, “Bingo Long and the Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings.”

And better yet, “Claudine.” This 1974 serio-comedy remains a beautiful, rough-edged romance starring Jones and Diahann Carroll, the latter replacing Diana Sands after a cancer diagnosis forced her to exit the project. Here you see Jones blending comedy, drama, explosive moments and intimate ones like an everyman sorcerer.

He played presidents and kings and garbage haulers and apartheid survivors (the national tour of Athol Fugard’s “‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys” starred Jones and Delroy Lindo, back in the early ‘80s, and I will never forget it). Through the decades, in worthy and less worthy material, the big man with the big, gorgeous basso profundo speaking voice found the gravity and the flinty heart in everything.

Thirty-seven years ago, we talked backstage after a Broadway press preview of “Fences.” It started with a detour: Jones, depleted but game after another grueling performance, said, “Let’s walk a bit” and we barreled out the stage door of the 46th Street Theater (now the Richard Rodgers) and around the corner so he could buy his nightly lottery ticket. “One of my vices,” he said, with that toothy grin, and seeing that grin up close was really something.

Back in his dressing room, Jones unpacked some of his struggles with “Fences.” He talked about the different gradations of audience laughter from night to night, and pre-Broadway city to city, stemming from Troy Maxson’s circumstances. “This is a character who comes on the stage representing something hopeful, especially for the Black female. He’s a strong man who has the chance to make something happen right, rather than just (mess) up. And then proceeds to (mess) up. It’s the last thing they want to see, because the audience has gotten pretty wrapped up in the play by then. And the laughter that’s derisive …” At that point Jones trailed off. Then he told me he wondered if he’d ever find the secret to reconciling “the comic punch of the first act with the tragedy of the second.”

Well. He did. He had already. Self-critical but honest about his strengths, Jones often realized little details he’d missed while the show was still running or the cameras were still rolling. He told one TV interviewer, years after he made “Field of Dreams,” that he wished he had found a way to have his novelist character register the loamy, earthy smell of the Iowa farmland, wordlessly but clearly, because filming the movie on location triggered the same sense memory in Jones’ rural upbringing.

He dealt with a severe stutter as a boy, vestiges of which remained with him for life. For years as a child he did not speak; risking more bullying and humiliation was deterrent enough. Then a teacher took an interest in improving this boy’s life, and he coached him in reading aloud, eventually with force and clarity and assurance. That, plus Jones’ estranged father’s own acting career, pointed the needle for a promising young talent.

Years later, long after his voice had entered the pantheon of great American actors’ great voices, he said: “When I read great literature, great drama, speeches, or sermons, I feel that the human mind has not achieved anything greater than the ability to share feelings and thoughts through language.” Jones is gone, but this is a day for celebration as well as sadness. So much of James Earl Jones’ own feelings and thoughts, expressed not wholly but thrillingly through language, will always be a rewatch and a re-listen away.

Michael Phillips is a Tribune critic.