A too-brief appreciation today, of a too-brief career of eccentric, often poignant delights.

Shelley Duvall died July 11 at age 75, after years of complications from diabetes. She died in Blanco, Texas, in her home state. After director Robert Altman met Duvall in 1970 at a party, he offered her a role and a plane ticket to Hollywood for his first post-“M*A*S*H” project, “Brewster McCloud.” She’d never been out of Texas before.

The movie world was not a childhood dream for Duvall, but she made that world her own in a career alternately championed or too often thwarted by her directors. She didn’t look or listen or hold a close-up like anyone else. She stood out as singular, tendril-like presence in an industry full of artificial plants.

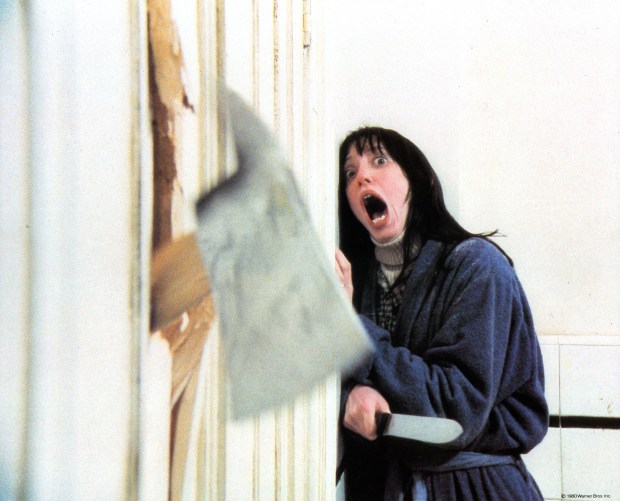

She’s best known, of course and unfortunately, for “The Shining,” director Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of the Stephen King novel about a marriage under some duress. Is she effective in the role of Wendy Torrance, stuck in the Overlook Hotel with a writer husband (Jack Nicholson) who is coping poorly and eventually homicidally with a supernatural dose of writer’s block? Yes, even if it half-destroyed her. Many have compared Duvall’s distillation of raw, gape-mouthed terror, egged on and overegged by Kubrick, to a certain semaphoric version of silent film performance. Her disintegration on screen wasn’t easy. Kubrick famously put her through hell and, in the big “Here’s Johnny!” scene with the axe, she endured 120-plus takes of methodical, repetitive, not-good-enough hysteria, commandeered by the man behind the camera.

I love parts of “The Shining,” including what Duvall does so relentlessly right at the edge of pure mania. You feel the actor’s nightmarish breakdown, plainly beyond the character’s. But in the wake of Duvall’s death, I hope we remember more than “The Shining” when we think of her.

She created so many different women, embodying such radically diverse eras and places, especially in Altman’s films (she did seven). We could start with Olive Oyl, of course, in Altman’s hilariously divisive “Popeye,” in which her overcooked-noodle stride and physicality remains what we might call “animation-plus.”

We could start with the forlorn mail-order bride in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” in which Duvall is a small but carefully delineated piece of a puzzle that floats like a dream.

She won the best actress prize at Cannes in 1977 for Altman’s hot, dry, harder-edged dreamscape “3 Women,” in which she is wonderful as the Sissy Spacek character’s ideal of domestic and womanly perfection.

You could also start with this: For the PBS series “The American Short Story,” writer-director Joan Micklin Silver delivered 45 minutes of charm in her blithe 1976 adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” the story of a tender Wisconsin woman intrigued by her flapper cousin’s mores and romantic options. Duvall’s striking face, her watchful, wide-eyed gaze and her just-right vocal inflections combined effortlessly in period pieces, this one especially.

Actors can sustain entire careers without finding directors who truly value what they and they alone can bring to a project. Kubrick did, but saw the role and the performer as raw material, ripe for caricature and arguable exploitation. But Altman, Joan Micklin Silver and a small clutch of other directors knew what Duvall had in her. And that’s why this day is sad, yes, but also a day to recall, happily, someone who managed so much work of plaintive, sneakily versatile and lingering impact.

Michael Phillips is a Tribune critic.